By Morag M. Kersel

DePaul University

December 2011

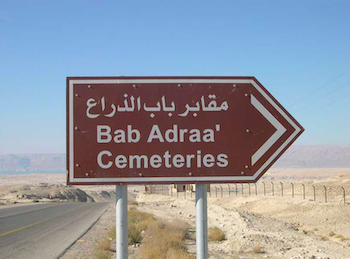

In the Dead Sea region of Jordan, reports of looting began as early as the 1920s when Alexis Mallon and W. F. Albright first identified the Early Bronze Age cemetery and settlement site of Bab edh Dhra’. During their foray to the Dead Sea – undertaken to fill lacunae in our knowledge of the “land and its antiquities” – Mallon and Albright were confronted with looted tombs, which led to an unearthing of both a mortuary site and a possible large open-air settlement. The site and its environs remained largely unexplored for the next 40 years until the early 1960s when Near Eastern archaeologist Paul Lapp noticed a flood of pots in the antiquities shops in Jerusalem and Amman unmistakably from Bab edh Dhra’. The provenience (archaeological findspot) for the pots was “reported to have come from the Hebron area,” an often used euphemism for an unknown, looted or laundered artifact, still in use today. Returning to Bab edh Dhra’, Lapp conducted three seasons of excavation in the cemeteries and the town site, excavating hundreds of pots and other grave goods. Archaeological artifacts excavated during this time were often divided using the standard system of partage (a division of finds between the excavators of sites and the national governments and sometimes the landowner). Under this system, Lapp and his associates were given a number of tomb groups, which made their way into institutional (museums and academic entities) collections. A detailed list of the various tomb group locations was published in the excavation reports so that theoretically anyone who wanted to access the entire corpus of material excavated by Lapp and colleagues from 1965-1967 should be able do so. But the life histories of these pots are not always so straight forward.

Any archaeologist will admit that their presence in a region can lead to increased awareness of the sites with positive or negative consequence. Often overlooked sites will become the objects of affection for locals who wonder why foreign archaeologists are poking around. The inevitable question “Are you looking for gold?” often accompanies archaeological investigation of sites. Why else would anyone brave the wet, the cold, the heat and/or the flies to work on an archaeological excavation or survey? Local interest in the mortuary sites of the Dead Sea Plain increased during the Lapp excavations and rose again in the 1970s, with the unearthing of pots, bracelets, basalt vessels and other associated grave goods as a result of development in the area by the Jordan Valley Authority. Further excavation (1997, 1979, and 1981) undertaken by Thomas Schaub and Walter Rast also ensured continued local interest in the area.

By the mid-1990s reports of devastating looting in this region of Jordan surfaced in the international news. Illegal excavation and the pillaging of sites in the area was thought to be a direct result of the development work undertaken by an Italian company building an irrigation system in the region in the 1980s. While digging deep trenches for the underground water system, the Italian employees uncovered large amounts of archaeological material, which were then taken back to Milan, the location of the company’s headquarters. Locals noticed the increasing interest of the Italian construction workers in owning a piece of the Jordanian past, so they began to conduct their own illicit excavations in order to supply the demand for artifacts from the Dead Sea Plain.

The Jordanian Provisional Antiquities Law no. 12 of 1976 made it illegal to trade in antiquities, forcing local Jordanian looters and dealers to find other markets for the material. Israel was, and continues to be, a lucrative market for these items, which are often marketed to Biblical tourists as “from the time of Abraham.” A number of networks and pathways involving different locals, middlemen, dealers in Kerak and Amman, Bedouin, diplomatic pouches, oil barrels on the Dead Sea, and pilots from Royal Jordanian Airlines arose in order to move material into neighboring Israel and Europe. Unfortunately, recent (March 2011) visits to both the EBA mortuary landscape in Jordan and the antiquities shops in Israel indicate that demand has not abated and looting continues.

Ongoing research under-

taken as part of the Follow the Pots Project investigation into the “social lives” (the various paths that objects take in their life history) of artifacts from the Early Bronze Age mortuary sites attempts to track pots from the ground (an EBI shaft grave) to the consumer. As part of this project, Meredith Chesson and I are trying to confirm that pots allocated as part of the original partage initiative are still located in their original institutional home. In early December, I travelled to the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas in an attempt to connect the dots on the Bab edh Dhra’ Tomb Group A 10. The Spencer has done a stellar job putting the collection online for researchers to access (see http://www.spencerart.ku.edu/), but I wanted to see firsthand the tomb group and any archival documents associated with its acquisition. How did a tomb group from the Dead Sea Plain in Jordan end up in Kansas? The original A 10 tomb group is still at the Spencer, but how it got there is not quite as straightforward as I had imagined. As I pieced together the past history and travels of these particular pots from a shaft grave at Bab edh Dhra’ to their current home in the Spencer, I have uncovered some interesting elements to their past lives. Pots from A10 have been grave goods, artifacts divided as part of partage, privately owned, educational items and exhibition pieces in the Spencer Museum of Art. In reconstructing the complete picture of the past we need to know about the many “lives” of Early Bronze Age pots. There are hundreds of tomb groups and pots out there and this research is in its infancy. So this is an appeal, too: if you know of Bab edh Dhra’ tomb groups in collections, please be in touch, so that together we might tell the complete story of these much loved, and venerated artifacts from the past.

Comments (1)

Looting and forgery are ugly cousins, I suppose. Looting gives forgers guidance on how to produce convincing pastiches and forgery that makes money increases the incentive to loot.

#1 - Martin - 12/23/2011 - 14:43

You may be able to find some materials from this area at :

Jeeninga Museum

Located in: Anderson University

Address: 1123 Anderson University Blvd, Anderson, IN 46012

They also seem to have contacts with other organizations who have other sets of the objects they have - in Australia and I believe they may have mentioned Japan. Thank you.