By W. Harold Mare, Ph.D.

Director, Abila Excavations

Professor, Covenant Theological Seminary

St. Louis, Missouri

March 2004

Then Jesus left the vicinity of Tyre and went through Sidon, down to the Sea of Galilee and into the region of the Decapolis (Mark 7:31).

Abila Excavation Histor

Abila (Quailibah, the modern name) in northern Jordan, just east of the southern end of the Sea of Galilee, is located about 13 kilometers north and slightly northeast of the modern city of Irbid. The site is composed of two hills (known as “tells,” mounds built up largely of ancient human remains over a period of 5500 years, from about 4000 B.C. to A.D. 1500)—a northern one named Tell Abila and a southern tell named Khirbet Umm el ‘Amad (“Mother of the Columns” in Arabic)—with a lower saddle area between them. Beginning with a survey in 1980 and continuing usually every other year (sometimes every year) from 1982 to 2000, Dr. W. Harold Mare, Professor at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri and Director of the Abila Archaeological Project and his teams have excavated at Abila, uncovering many fascinating objects, artifacts, and structural remains that have added considerably to our understanding of life in the ancient Near East from before the Old Testament period and beyond New Testament times.

When the survey and excavation started in 1980 and 1982, Dr. Mare and his staff saw on a part of Umm el ‘Amad the scattered columns of what was thought to be an ancient temple, but which, on excavation, turned out to be a seventh- to eighth-century A.D. Christian church. On the northern edge of this sector the excavators saw the cavea of the Graeco-Roman “theater” which bordered the south edge of the central saddle. Part of a wall ran north across this central saddle toward Tell Abila; building ruins were also seen in the saddle area. To the west of the “theater,” north of the seventh-/eighth-century church ruins, was an olive orchard, on the north edge of which were ruins of the west “bridge” or vault over a gate that was part of the north-south road which, in Roman times, was called the Cardo Maximus.

Along the south crest of Tell Abila were the remains of an ancient wall which, when excavated, turned out to be the acropolis wall of the city, originally constructed in the Iron Age (1200-586 B.C.) and added to in the Hellenistic/Greek and Roman periods. On the top of Tell Abila in its south sector were seen ruins of what at first was designated as a “public building,” but on excavation turned out to be a three-apsed sixth-century A.D. Christian basilica. Over toward the northeast slope of the tell was found a small semi-circular cavea that may be the remains of an ancient music hall (called in Greek an “Odeon”) similar to the one in the marketplace of ancient Athens. Numerous other ruins on the top of Tell Abila, when finally excavated from 1982 to 2000, included walls, buildings, and other structures going back to 3000 B.C. through the Islamic, Byzantine, Roman, Greek, Iron, and Bronze ages. In addition, the excavation of tombs and tomb complexes in Abila’s extensive cemetery has brought to light much cultural information about the lives of the people who inhabited the site from the Bronze Age through the Byzantine period.

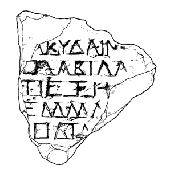

“Abila” in Greek, is inscribed on the second line of this stone excavated on Tell Abila in 1984.

“Abila” in Greek, is inscribed on the second line of this stone excavated on Tell Abila in 1984.

Tell Abila is bordered on the north by Wadi (Valley) Abila, and both Tell Abila and Khirbet Umm el ‘Amad are bordered on the east by Wadi Quailibah. The cemetery areas for the site of Abila (probably including as many as 1000 tombs and tomb complexes; we have excavated over 100 of these so far) run along the slopes of Wadi Quailibah, extending to the south of Khirbet Umm el ‘Amad about three-fourths of a kilometer, then southwest around the wadi to a perennial spring, Ain Quailibah. The waters of this spring run north in Wadi Quailibah to Abila where the excess has helped water a large grove of pomegranate trees. The water continues to flow north in Wadi Quailibah under the ancient stone bridge which connected Abila with its eastern extremity and also with cities and communities to the east and then flows on to the Yarmouk River about 5.3 kilometers north of Abila. The Yarmouk River flows west to empty into the Jordan River just below the Sea of Galilee. Further cemetery areas are found east and northeast of Tell Abila along the slopes of Wadi Quailibah and along the slope of Wadi Abila on the north of Tell Abila.

In addition to the discoveries described above, over the course of surveying and excavation from 1980 to 2000, the Abila teams have excavated five Christian churches, a Byzantine shrine, an Islamic fortress-palace, an extensive underground aqueduct system that brought water to the center of Abila and to its Roman bath house and nymphaeum, an ancient olive press, a Roman villa, and other structures.

Although the evidence from the 1980 survey and subsequent excavations have clearly shown that the archaeological history of Abila extends from Islamic and Byzantine times at least as far back as the Early Bronze period, the ancient written sources focus attention particularly on one part of that history—the site’s importance in the Hellenistic/Greek, Roman, and later periods, but especially on its connection with the cities of the Decapolis.

What is the Decapolis?

The meaning and significance of the term “Decapolis” and the cities associated with it have long intrigued scholars. Linguistically and etymologically the term Decapolis (Δεκάπολις) means “ten cities,” but according to ancient sources the number of cities in the group known as the Decapolis varied from ten to eighteen or nineteen. Pliny, in his Natural History (5, 74) under the heading “Decapolis,” lists Damascus, Philadelphia, Raphana, Scythopolis, Gadara, Hippos, Dion, Pella, Galasa (i.e., Gerasa), and Canatha; he then mentions what he calls Tetrarchies (kingdoms), listing among them Trachonitis, Panias (“in which is Caesarea with the aforesaid spring”), Abila, etc. Inasmuch as this Abila is mentioned in connection with Trachonitis and Paias-Caesarea, both located in the north of the Palestine area near the Sea of Galilee, it is likely that Pliny is referring to the Abila near Gadara and Capitolias and not the Abila located farther south in Peraea near Livias, nor the Abila of Lysanias located west and north of Damascus.

Pliny then goes on to suggest (Natural History 5, 74) that not all writers include the same cities in their lists when referring to the Decapolis. Evidence of this is seen in the list given in the second century A.D. by the geographer Ptolemy (Geography, 5, 14, 22) who, while omitting Raphana, includes the other nine cities mentioned by Pliny and adds nine more of his own, as follows: Heliopolis (presumably Baalbek), Abila (Quailibah; our Abila), Saana (Sanamyn), Ina, Abila of Lysanias (near Damascus), Capitolias (Beit Ras), Adra (Edrei, Der’a), Gadora, and Samoulis. This makes a total of nineteen cities, counting Raphana; but if Raphana is the same as Capitolias, as some have argued, then there are at least eighteen cities that were regarded as being part of the Decapolis. In light of these lists, we posit that the Decapolis group was located geographically east of the Jordan River and the Sea of Galilee (except for Nysa-Scythopolis at Beth-Shan on the West Bank) in Transjordan and ancient Syria.

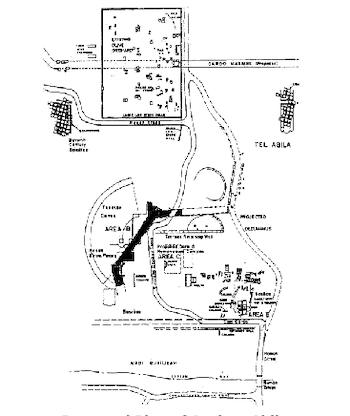

Proposed Plan of Ancient Abila

Chronologically, the Decapolis cities seem to have come into existence as such during the time of Hellenization following the conquests of Alexander the Great. Spijkerman comments:

Both the more ancient cities, and the newer ones founded in the Persian period (such as Gadara, Hippos, Gerasa, Abila, Dium, Capitolias) revived as political centers of the region at the time when Hellenism appeared and attempted, through its policy of urbanization, to deeply permeate the century-old oriental milieu, so radically different both culturally and religiously. From that time on the history of the cities became the history of the region. They became πόλεις ‘Ελληνίδες, that is, city-states with a republic constitution patterned on the Greek model: though theoretically they were autonomous and territorially independent, within the general framework of the Seleucid or Ptolemaic empire.

This Hellenistic urbanization of the region began in the north where we find certain cities like Gerasa, Pella, Capitolias and Dium claiming to have had Alexander the Great as their founder! In reality the first foundations which can be documented are of the Ptolemaic epoch like Philadelphia-Amman and Nysa-Scythopolis.

Those Decapolis cities other than the ones mentioned above seem to have been founded as such a little later, following the Battle of Panias in 198 B.C., when the Seleucids of Antioch finally conquered the Ptolemaic empire of Egypt and the Decapolis region passed into Seleucid control. Yet despite this control, the Decapolis cities seem to have had some sort of autonomy similar to other small autonomous states such as Iturea, Nabatea, and Judea, which appear to have arisen at least partly as units of political opposition to an area that was considered to be a center of foreign influence and power. Further evidence for this autonomy is seen in the fact that Judea, under the Hasmonean priest-kings, apparently perceiving the Decapolis cities as a political threat, conquered many of them.

Though the existence and significance of the Decapolis region is well attested, the nature of this group of cities is largely unknown. Was it some kind of a confederation tied together by political, military, economic, social, and religious bonds or some combination thereof? Certainty on this is not possible. What we do know for sure is that by the time of the Roman conquest in 64/63 B.C. the Decapolis cities constituted a distinct unity as far as their geographical area was concerned. And by New Testament times this region seems to have been flourishing, as evidenced by the references to the group (but not to individual cities within the group) in the Gospels (that is, specifically Matthew 4:25, Mark 5:20, and Mark 7:31)

History Waiting to be Uncovered

In the light of the literary and archaeological history of Abila and the other cities of the Decapolis region—a history that covers the pre-Old Testament, Old Testament, New Testament, Early Church, and Islamic periods—continued excavation in this region is essential for a fuller understanding of these cities and the roles they played in each of these periods.

We invite anyone with an interest in such an endeavor to join us for our Abila 2004 Excavation, set for June 19-August 7. Professors at colleges, universities, and seminaries, and other professionals with expertise in excavation, geology, anthropology, architecture, mosaics, etc.; student volunteers, both graduate and undergraduate; and interested, dedicated lay people from all walks of life have a wonderful opportunity to work side by side with such renowned scholars as Dr. David Chapman, Covenant Seminary; Dr. Jack Lee, St. John Fisher College; Dr. Reuben Bullard, University of Cincinnati; Dr. Robert Smith, Roanoke Bible College; Dr. Susan Ellis, Wayne State College; and many others in helping to uncover more of the fascinating history of this important Bible lands city.

Abila, Area D, Christian church, threshold into a side room.

Excavation Goals for 2004

Even though much of value for our understanding of Middle Eastern life during biblical times has been uncovered at Abila, much more work remains to be done. Our goals for the upcoming excavation season are ambitious. We plan to

1. Excavate further to the east and north of the partially reconstructed (in 2000) sixth-century A.D. church basilica on Tell Abila (the north tell) to discover additional evidence of the many archaeological periods represented there. These range from the Late Islamic back through the Early Bronze periods.

2. Excavate along the outside of the south side of the seventh- to eighth-century A.D. basilica on the south tell, Tell Umm el ‘Amad, to uncover additional side rooms of the Area D church there.

3. Excavate down to bedrock in the area of the proposed theater in the civic center. Also in this area, we will work on restoring the Umayyad palace/fortress built within the theater cavea; probe into the internal structure of the nearby bath house ruins; excavate the areas to the west and south of the sixth-century cruciform cathedral; and continue excavating the single-apse church on the hilltop east of the theater.

4. Expand the tomb excavations all along Wadi Quailibah on the east side of Abila, looking for and excavating tombs from the Bronze Age through the Byzantine period.

With so much work to be done, many helping hands are needed.

Abila, Area B, theater area, excavating down into the Roman period.

An Exciting Educational Experience

Excavation team members not only contribute to an important work and experience the thrill of reaching back into history and touching it in person but also are privileged to interact closely with the contemporary people and culture of the area. There are many other benefits of joining the Abila 2004 Excavation team:

- Students can earn four (4) hours of academic credit, either through Covenant Theological Seminary or through his or her own college, university, or seminary.

- All participants will have access to an essential reading list of archaeological and technical articles and of Abila’s field reports to help them prepare for and engage in the excavation season.

- All participants receive intensive training in camp and in the field on the essential principles of archaeological excavation. You’ll then practice these techniques as you work in the field assisting experienced archaeologists in actual excavations.

- You will acquire valuable experience through working in the camp laboratory and registry, assisting with pottery identification and labeling, drawing, etc.

- You will increase your knowledge and understanding of the work you are doing in the field with scholarly lectures on archaeological and multi-disciplinary subjects. These lectures take place in camp during the week. Subjects include the history of Jordan, ceramic typology, epigraphy, osteology, geology, etc.

- Carefully planned weekend educational trips to other important archaeological sites in Jordan are offered at minimum, shared cost.

- Following the dig, participants can elect to visit (at their own expense) other sites in Israel, Egypt, Greece, Europe, etc.

Approximate Expenses to Participate in the Abila Excavation, June 19-August 7, 2004

- Round-trip airfare costs, New York to Amman, Jordan—approximately $1400 per person.

- Board and room/general fee for seven weeks at the Staff Headquarters (near Abila)—$1400 per person.

- Weekend expenses, pre- and post-season expenses, and incidental expenses are to be borne personally by each participant.

For further information and an application, contact:

Dr. W. Harold Mare,

President, Abila Archaeological Project, and Director, Abila Excavations

Covenant Theological Seminary, 12330 Conway Road, St. Louis, MO 63141, U.S.A.

Phone: (314) 434-4044, ext. 339; E-mail: whmare@aol.com

Also, visit our Abila website for more information and downloadable forms.

The Abila 2004 Excavation is sponsored by the Abila Archaeological Project and Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri, and endorsed by the Near East Archaeological Society.

Thank you