My analysis suggests that the cumulative linguistic evidence aligns most coherently with a pre-exilic dating of Isaiah 40-66. In fact, a post-exilic dating would require such extensive redating of other books that the traditional Classical vs. Late Biblical Hebrew distinction becomes unstable.

See also Linguistic dating und das Jesaja-Buch: eine Untersuchung der sprachlichen Entwicklung des Hebräischen im Jesaja-Buch sowie ihre Auswirkung auf die Datierung des Buches und auf die Verwendung des Linguistic Dating im Allgemeinen (Ph.D. dissertation, 2024).

By Samuel Koser

Part-time Lecturer

Bible Study College, Ostfildern

November 2025

Can linguistic analysis determine the date of a Biblical Hebrew text? Over the past five decades, the practice of linguistic dating has gained considerable popularity as a method for this purpose. At the same time, the method has also been widely criticized and debated for its viability.

Just under six months ago, the article “Isn't It Time to Break Up with Linguistic Dating? Rethinking Hornkohl's Method—and What Comes Next” by Rezetko et al. appeared here on The Bible and Interpretation.

The key question, then, is: Should greater consideration be given to the language used to date Biblical Hebrew texts? Or, on the other hand, should linguistic dating simply be abandoned?

I was able to explore this question in my doctoral dissertation using the example of the book of Isaiah.[1] The book of Isaiah provides a particularly illuminating case study: Researchers have reached completely contradictory conclusions regarding the period in which especially Isaiah 40-66 should be categorized on the basis of language. While some say that the language is an argument for Isaiah 40-66 having been written before the exile,[2] others say that the language in Isaiah 40-66 clearly points to the post-exilic period,[3] and still others say that the language of Isaiah 40-66 can best be classified as belonging to the exilic period.[4]

In my study, I demonstrate that there is a need for more rigorous methodological consideration of linguistic dating in certain areas.[5] Indeed, more than two-thirds of the linguistic features proposed for dating the book of Isaiah do not withstand rigorous scrutiny.[6]

Nevertheless, there are some linguistic features that appear to support a pre-exilic or post-exilic classification of text blocks within the book of Isaiah. However, these features only do so if certain methodological and logical points are taken into account. The results of individual features always depend on the assumptions made about the dating of other books and shift depending on these assumptions.

In the following, I would like to present and evaluate individual results of my dissertation on the book of Isaiah and linguistic dating. This will be done in two steps: First, I will give three concrete examples to illustrate three common methodological problems. Second, I will show which methodological steps I have incorporated and developed in my study in order to better classify the linguistic results on the book of Isaiah.

1. Three methodological difficulties of linguistic dating using the example of the book of Isaiah

In my study, I first compiled all the features – just under 100, depending on how they are counted – that have been cited until now for dating different parts of the book of Isaiah to different eras, and evaluated them. Many of these revealed methodological difficulties and unclear distributions. I would like to highlight three difficulties that occur more frequently, using three examples from my dissertation.

1.1. Unclear assumptions lead to wrong decisions, using the example of “gather,” ḳavats (קבץ) / asaf (אסף) or kanas (כנס)

Rooker cites one feature as evidence that Isaiah 40-66 represents pre-exilic Hebrew (Classical Biblical Hebrew or CBH): the use of different verbs for “gather”: ḳavats (קבץ) / asaf (אסף) or kanas (כנס).[7] There are two verbs that are frequently used in Biblical Hebrew for “gather”: asaf (אסף) 204 times and ḳavats (קבץ) 127 times in the entire Old Testament. According to Rooker, kanas (כנס) is used instead in post-exilic Hebrew. Kanas (כנס) does not appear at all in Isaiah 40-66, but asaf (אסף) or ḳavats (קבץ) appear 22 times.[8] According to Rooker, this indicates pre-exilic Hebrew in Isaiah 40-66.

On closer inspection, several points stand out: 1. Overall, the theme of “gathering” and the two corresponding verbs appear particularly frequently in Isaiah in comparison to the rest of the Old Testament. 2. Kanas (כנס) is used only eleven times in the Old Testament,[9] one of which is in Isaiah 28:20. Only three occurrences are in so-called undisputed post-exilic books (Esther, Nehemiah, Chronicles). It appears twice in Ezekiel, twice in the Psalter (Psalms 33, 147), and three times in Ecclesiastes. What does this imply? Only if Ecclesiastes and the two psalms are counted among the post-exilic books would the distribution be noticeable. If these books are dated to the post-exilic period, the occurrence of kanas (כנס) is an indication of post-exilic Hebrew.

But on the other hand, can the absence of kanas (כנס) in Isaiah 40-66 be used as an argument against post-exilic Hebrew (Late Biblical Hebrew or LBH), as Rooker argues? No, because the other two verbs for “to gather” are also regularly found in post-exilic literature. Kavats (קבץ) also occurs very frequently in LBH: five times in Ezra, five times in Nehemiah, 14 times in Chronicles (eight of which have no parallel text in Samuel/Kings), three times in Esther and twice in Zechariah.[10] The situation is similar with asaf (אסף), which appears twice in Ezra, four times in Nehemiah, 18 times in Chronicles (twelve of them without parallel text in Samuel/Kings), once in Daniel, three times in Zechariah, and six times in Ezekiel in exilic Hebrew.[11] Thus, the two verbs are not noticeably less frequent in LBH than in CBH. Therefore, the mere absence of kanas (כנס) and a few occurrences of asaf (אסף) and ḳavats (קבץ) in Isaiah 40-66 cannot be used as an argument for CBH.

What does this example show? A great deal depends on the assumptions made about the dating of books. Esther, Nehemiah and Chronicles are undisputedly post-exilic books. But only if Ecclesiastes and the two Psalms 33 and 147 are dated to the post-exilic period can the occurrence of kanas (כנס) speak in favour of post-exilic Hebrew. At the same time, it is of course crucial to which time period Ezekiel and other books are dated. If, on the other hand, we assume in this example that one of the Psalms or the book of Ecclesiastes was written before the exile, the characteristic would vanish into thin air, as it would appear relatively quickly with equal frequency in pre-exilic and post-exilic contexts due to its few occurrences. This demonstrates clearly that the assumptions one makes about the dating of other books are crucial for assessing characteristics. Many characteristics only appear to have a clear distribution if one has corresponding assumptions about books, or, on the other hand, disappear into thin air if one no longer has these assumptions.

1.2. The distribution of a characteristic and a necessary frequency for a dating reference are not critically examined, using the example of the emphatic infinitive absolute

The previous example already illustrates a second methodological difficulty. Rooker believes that the absence of kanas (כנס) in pre-exilic Hebrew in Isaiah 40-66 speaks in favour of this. This is invalid if one considers the distribution and notes that the verb occurs only eleven times in the Old Testament and is also very rare in post-exilic books. Even in the Chronicles, the verbs asaf (אסף) and ḳavats (קבץ) are used for “to gather” except for one example (similar to the book of Isaiah). Other post-exilic books such as Daniel (in the Hebrew part) or Ezra even use only these two verbs for gathering, as does Isaiah 40-66. Thus, upon closer examination of the distribution, this characteristic for Isaiah 40-66 cannot be considered a valid characteristic for pre-exilic Hebrew.

A critical examination of the distribution of a feature is therefore necessary in order to assess whether the feature, given its frequency in a book, actually constitutes a meaningful feature for dating it to a particular period. A second example from the book of Isaiah illustrates this point even more clearly: the emphatic infinitive absolute. In Hebrew, the verb form infinitive absolute is often used in such a way that a verb in infinitive absolute appears directly with its same verb root in a final form – this is referred to as the emphatic infinitive absolute.

Hays argues that the use of the emphatic infinitive absolute declined in post-exilic Hebrew (LBH). Since it appears several times in Isaiah 24 (vv. 3, 19, 20), this suggests pre-exilic Hebrew (CBH).[12] This development of the emphatic infinitive absolute can be seen primarily in prose texts: while in CBH the infinitive absolute is very often used to precede a finite verb of the same verb root, presumably to reinforce it, this usage declines significantly in LBH. Overall, the emphatic infinitive absolute is used about 500 times in the Old Testament. In the prose texts of undisputed post-exilic texts, there are only eleven occurrences of this usage.[13] In Chronicles, four of the passages have parallels in Samuel/Kings.[14] Thus, only three occurrences can be considered independent in Chronicles. This shows that individual occurrences of the emphatic infinitive in prose texts cannot yet be used as an argument for CBH, but frequent occurrences certainly can.

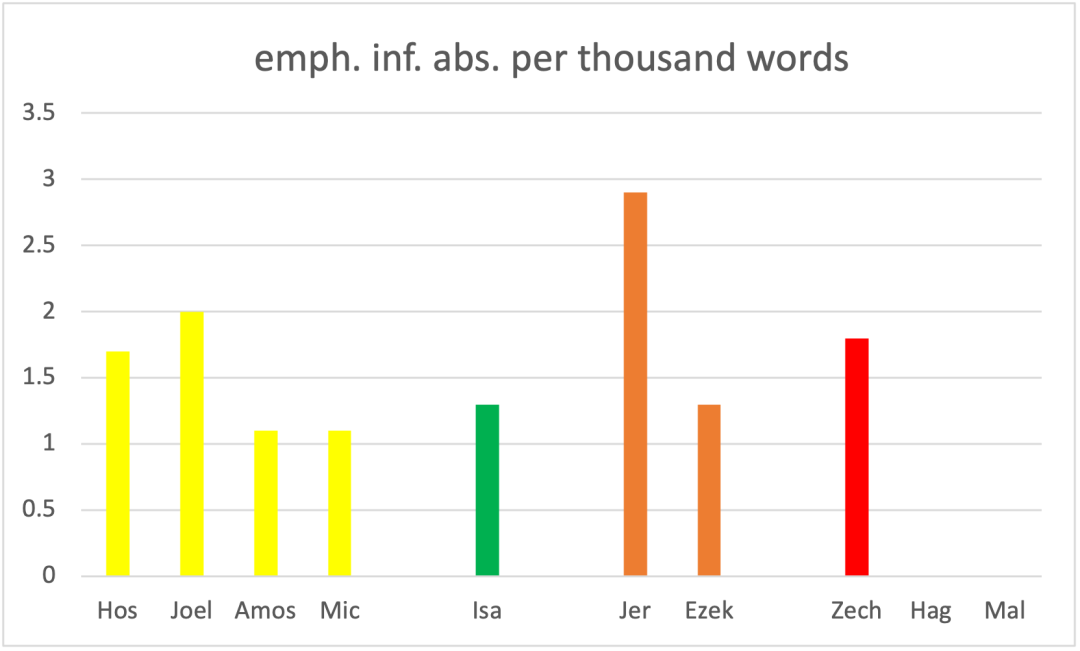

But what about prophetic literature? Below is a diagram showing how often the emphatic infinitive absolute is used per thousand words in some of the prophetic literature:

While Haggai and Malachi do not use the emphatic infinitive absolute at all, and Ezekiel has a rather low number of 1.3 per thousand words, there is one example in particular that significantly weakens this characteristic. In Zechariah, the emphatic infinitive absolute is used six times in this way, or 1.8 per thousand words.[16] Throughout the entire book of Isaiah, the emphatic infinitive absolute occurs 22 times (spread throughout the book).[17] Since the book of Isaiah has more than five times as many words as Zechariah, the occurrences in Isaiah per 1000 words are lower than in Zechariah: 1.3 per 1000 words in Isaiah and 1.8 per 1000 words in Zechariah. A comparison with Ezekiel, an exilic prophet, shows that the emphatic infinitive occurs 25 times, or 1.3 per thousand words, as in Isaiah.[18] Thus, the occurrence in the books of Isaiah, Ezekiel and Zechariah is very similar (also to the other prophets I have used for comparison), and the use of the emphatic infinitive absolute cannot be used as a chronological linguistic feature for CBH in prophetic books as it can in prose texts. The mere frequency of this construction does not necessarily imply that these chapters must have been written at a different time, as such examples can always occur due to random distribution and accumulation.

What does this mean? The distribution of features must always be questioned critically and also in relation to genre. In this example, it has been shown that, although the emphatic infinitive absolute is used significantly less frequently in prose texts in the Old Testament after the exile, in prophetic texts we see little difference between the (possibly) pre-exilic prophets, Isaiah, Ezekiel and Zechariah. Jeremiah uses the emphatic infinitive absolute most frequently in relative terms among the prophetic books. Haggai and Malachi do not use it at all, but this is not particularly noticeable due to their short form, since even in the book of Isaiah, for example, there are several chapters without the infinitive absolute. Once a counterexample is found, the feature ceases to be meaningful and remains, at best, a weak indicator. In this case, Zechariah (and other prophets often classified as pre-exilic) uses the infinitive more frequently than Isaiah per thousand words. Therefore, this feature cannot be used to date Isaiah or parts of the book to the pre-exilic period.

1.3. Alternative explanations are not sufficiently considered, using the example of a preference for plural forms

A third major methodological issue is the insufficient consideration of alternative explanations for linguistic variation. Just because there is a noticeable distribution or shift in a feature does not necessarily mean that it is chronologically determined. The differences may also be due to dialects (regional language differences), sociolects (language differences of certain social groups) or idiolects (personal style preferences). In addition, a linguistic feature may be related to the chosen genre, as we saw with the latter feature in 1.2. It is also always necessary to consider whether a feature that appears is possibly an archaism (imitation or adoption of an older style), whether there has been an update (the linguistic feature has been adapted to the later style in a text revision), or whether an older text tradition has been included. An example where a linguistic difference is noticeable but should not be explained chronologically is the plural form of ḥaṭat (חַטָּאת) (“sin”). Scholars have repeatedly observed that in post-exilic Hebrew, the plural form is preferred for some nouns.

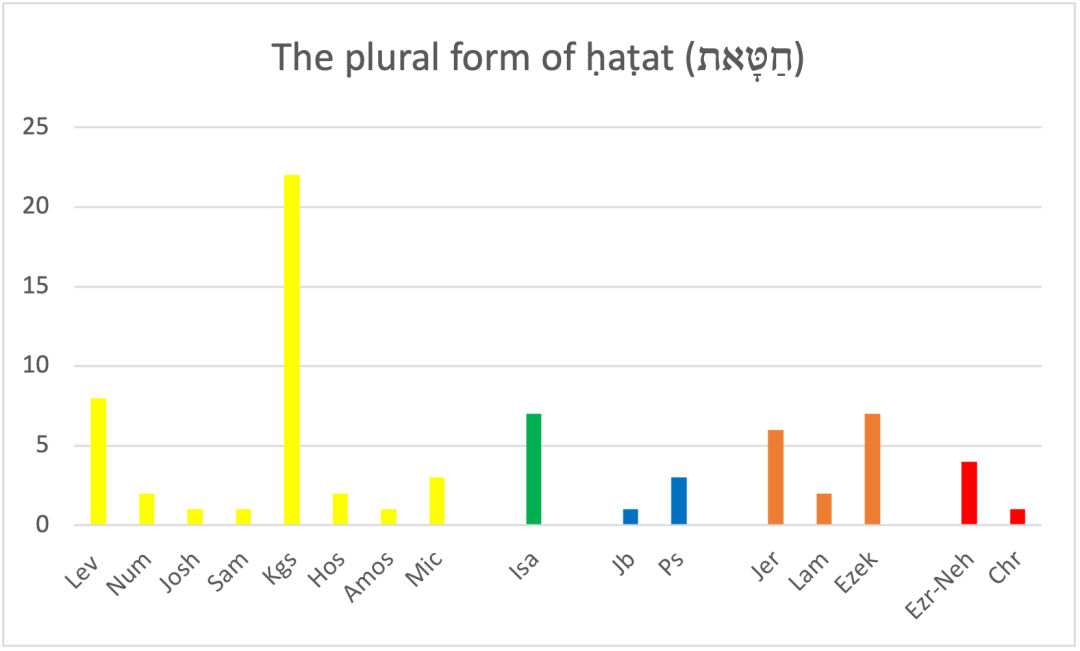

For Isaiah 40-66, Hays cites the noun ḥaṭat (חַטָּאת), which always appears in the plural in Isaiah 40-66: 40:2; 43:24-25; 44:22; 58:1; 59:2, 12.[19] It is certainly striking that the noun appears in the singular only in Isaiah 1-39 (4x) and in the plural only in Isaiah 40-66 (7x).[20] This distribution is conspicuous and requires explanation. Can the distribution best be explained chronologically – i.e. that Isaiah 1-39 can be classified linguistically as pre-exilic and Isaiah 40-66 as post-exilic?

What is the distribution of the plural form of ḥaṭat (חַטָּאת) in the Old Testament?

The plural form of ḥaṭat (חַטָּאת) occurs 71 times in the Old Testament, but mainly in pre-exilic Hebrew. It appears only five times in undisputedly post-exilic books (once in Chronicles and four times in Ezra-Nehemiah), but most frequently in the book of Kings (22x). Therefore, there is no evidence from this plural form to derive an indication of LBH. For the striking distribution in the book of Isaiah and the difference between Isaiah 1-39 and Isaiah 40-66, an explanation other than the chronological one must be sought, since the plural form of ḥaṭat (חַטָּאת) is not used more frequently in LBH. There may be a contextual explanation for why the author changed. Or it may be due to an idiolect: if two different authors had written Isaiah 1-39 and 40-66, this could also explain the difference. A detailed discussion of this lies beyond the scope of this article. However, it has been shown that the plural form of ḥaṭat (חַטָּאת) in Isaiah 40-66 cannot be an indication of post-exilic Hebrew, and an alternative explanation must be found for the striking difference within the book of Isaiah.

This example again demonstrates that the distribution of the feature as a whole has not been carefully examined. Although it is striking that there is a change from the singular to the plural of ḥaṭat (חַטָּאת) between Isaiah 1-39 and Isaiah 40-66, overall there is no shift from pre-exilic to post-exilic Hebrew in this noun. Thus, the change in Isaiah must be explained differently and an alternative explanation sought.

1.4. Interim conclusion

The examination of three representative linguistic features in Isaiah has shown that the methodological foundations of linguistic dating require far greater precision than is often assumed. First, the dating of individual features is deeply dependent on prior assumptions about the chronological placement of other biblical books – assumptions that are frequently unstated and rarely tested. Second, even supposedly clear linguistic markers lose their force when their overall distribution, frequency, and genre sensitivity are examined critically. Third, linguistic variation can arise from multiple factors other than chronology, including genre, dialect, sociolect, idiolect, archaism, updating, or the incorporation of older textual traditions. Taken together, these observations reveal that a substantial proportion of the linguistic arguments traditionally used to date Isaiah do not withstand close scrutiny. Yet this does not invalidate the potential of linguistic dating altogether. Rather, it highlights the need for more carefully articulated assumptions, more nuanced evaluation of the strength of features, and more systematic consideration of alternative explanations. With these difficulties in view, the next step is to ask how linguistic dating might continue to be practiced responsibly. In the following section, I propose three methodological refinements designed to address the problems identified so far – clarifying assumptions, assessing the strength of features more rigorously, and integrating alternative explanations into the interpretive process. These steps, taken together, offer a pathway toward a more reliable and fruitful application of linguistic analysis in the dating of biblical texts, including the book of Isaiah.

2. Three proposed solutions for how the linguistic dating method can continue to be fruitful in the future

The first part highlighted three common methodological difficulties of linguistic dating: unclear assumptions, distribution of linguistic markers, and alternative explanations. In this section, I would like to present three proposed solutions for how these methodological weaknesses can be avoided in the future in order to conduct linguistic dating on a better basis.

2.1 Clarifying assumptions and adopting flexible models as safeguards against cognitive closure

Since linguistic dating is always based on assumptions, these should be clearly stated. Which biblical (or non-biblical) books are assigned to which era in order to discover linguistic features that differ chronologically? It also helps to keep models flexible, which is becoming increasingly easier thanks to computer analysis. For example, if 20 linguistic features are examined in Isaiah, it is possible to consider retrospectively: Under which assumptions are these features meaningful or meaningless, and for which period do they speak? For example, the verb כנס may indicate post-exilic Hebrew if both certain Psalms and Ecclesiastes are also dated to the post-exilic period. As soon as one of the Psalms or the book of Ecclesiastes is not post-exilic, the verb can no longer be an indication of post-exilic Hebrew due to its overall rarity.

If one takes into account the dependence of the characteristics on the dating of certain books, one can consider in retrospect: Under what conditions do which characteristics speak for which epoch? What linguistic challenges do certain dates pose? And which dates result in the most “uniform system” possible?

In my dissertation, I used the example of Isaiah 40-66 to show that pre-exilic, exilic and post-exilic dating of most of the text presents certain linguistic challenges that need to be explained. Depending on how other books are dated, these linguistic features can be explained and classified more easily or with greater difficulty. If one dates Isaiah 40-66 as pre-exilic, one must deal with a few linguistic features that tend to favour a post-exilic date. However, these are all also linked to the dating of controversial books.

I have examined this from every angle and will show here just one example of how this is possible:

If one wishes to classify large parts of Isaiah 40-66 as post-exilic, there are certain difficulties with some linguistic features that tend to appear in pre-exilic Hebrew (again, depending on other dating, of course). 17 such features have been confirmed in my work and tend to favour pre-exilic Hebrew in Isaiah 40-66. For example, if one were to classify large parts of the book of Proverbs as post-exilic, this would greatly weaken or completely eliminate six of these 17 features, because they would then also be found in the post-exilic Proverbs. If one were to classify many of the Psalms as post-exilic, this would affect four more features. This shows that all linguistic features that could indicate a specific date are strongly dependent on the dating of other books. If Isaiah 40-66 is dated to the post-exilic period, but many of the “controversial” books are dated to the pre-exilic period (such as Proverbs or many of the Psalms), then difficulties arise with the language in Isaiah 40-66 that need to be explained. However, if one dates Proverbs and many of the Psalms, as well as Ruth and Job, for example, to the post-exilic period, there are hardly any linguistic difficulties in classifying Isaiah 40-66 as post-exilic. However, due to the many “classical” pre-exilic features found in Isaiah 40-66, one would then have to consider whether the chronological division into CBH (pre-exilic Hebrew) and LBH (post-exilic Hebrew) is tenable at all.

The guiding principle should therefore always be: What are my assumptions? What linguistic features for dating arise from them? And in retrospect, we must consider: How do these features change when the assumptions shift? Are there variants in which a coherent linguistic development model emerges and others in which the linguistic differences are, at least so far, more difficult to explain?

In my dissertation, I came to the conclusion that, based on the book of Isaiah and specifically Isaiah 40-66, the division into CBH and LBH must be fundamentally questioned if Isaiah 40-66 is classified as post-exilic. On the other hand, a pre-exilic classification of Isaiah 40-66 can best be justified from a linguistic point of view if books such as Job, Ruth, Proverbs, Zephaniah and many of the Psalms are also classified as pre-exilic – if this is not done, a pre-exilic classification of the book is rather challenging from a linguistic point of view. Classifying some of the debated books, along with Isaiah 40-66, as pre-exilic would better demonstrate pre-exilic linguistic features and a chronological development of the Hebrew linguistic styles CBH and LBH.

2.2. The significance and strength of the characteristics must be examined and determined in order to be able to make a reliable assessment at the end

The second methodological weakness can be remedied by critically examining whether, depending on both the underlying assumptions and the frequency with which the feature occurs, a linguistic feature can be said to indicate a particular era.

It can also be helpful to assign different levels of significance to the linguistic features, as not every linguistic feature is equally meaningful. For example, if a word that is used more frequently in the pre-exilic period but also in the post-exilic period appears several times in the section under investigation, this is only a weak indication of a pre-exilic date. On the other hand, if a word that is only found in the pre-exilic period also appears in the section under investigation, this is a very meaningful argument. In my study, I have divided the features into four categories based on forensic linguistics: from “very significant” to “significant,” “less significant” to only a “weak indication” (or none at all, in which case these features can be discarded). I assigned numbers (from 1 to 4) to this classification in my work so that I could summarise retrospectively how strongly all the characteristics together support classification in a particular era. Of course, it is impossible to assign an exact significance to a linguistic feature; for example, a linguistic feature with a strength of four is not exactly four times as significant as a linguistic feature with a strength of one. So does it make sense to divide them into four different strengths? Yes, because even if linguistic features cannot be assigned an exact significance, it is still possible to say roughly whether a feature is only a weak indication, not very significant, significant or very significant. In contrast to the previous approach, in which features were usually simply counted, without regard to their relative strength, the division into four different categories is definitely more accurate. For example, my study has shown that (depending on assumptions, of course) in Isaiah 40-66, 17 linguistic features with a strength of 42 point to pre-exilic Hebrew, while 7 linguistic features with a strength of 15 point to post-exilic Hebrew. It would be incorrect to conclude from this that Isaiah 40-66 is best classified as exilic, since features of both periods do not appear in the same way in the exilic period – but I cannot go into this in more detail here.

2.3. All alternative explanations should be examined and weighed up

To address this third methodological challenge, in the future, for each linguistic feature examined, consideration should be given to the extent to which an alternative explanation is conceivable.

The first thing to consider is: Could the feature have been easily archaicized or updated? For example, in the case of syntactic or some grammatical features whose shift was not yet complete, archaization and deliberate imitation are very unlikely, as it cannot be assumed that the author at the time was aware of this subtle shift in language. If this is considered for each feature, it is possible to reflect afterwards on whether a large proportion of the features identified can be explained by archaization. If only a few of them can be explained well by archaization, this is not a good objection to the language classification.

Secondly, the question must be asked: Could the feature be traced back to the use of an older text tradition? To this end, it is always necessary to consider the extent to which linguistic features occur only in individual chapters or sections, and ultimately, when all the features have been compiled, it can be considered whether the chronological attribution is only meaningful for certain sections that may have been taken from earlier textual traditions. Generally speaking, nothing can be said about individual words, verses or smaller sections on the basis of the language alone. If, for example, earlier Hebrew features appear specifically in one chapter or section of Isaiah 40-66, this could well be explained by the use of an older text tradition at that point. If the pre-exilic features appear scattered throughout Isaiah 40-66, this alternative explanation is unlikely.

Finally, we must consider whether an alternative explanation is possible through dialect, sociolect or idiolect. This must be evaluated individually for each feature based on its distribution. For parts of the book of Isaiah, one could assume a southern Hebrew dialect or attribute some formulations to the dialect of an upper class, as the book of Isaiah probably belonged to this class. However, there is little supporting evidence for the former, and in the latter case, it is important to keep in mind whether a formulation or feature can be specifically attributed to this class. Sociolect is closely linked to genre. Therefore, it is always necessary to consider whether a feature is only applicable in prose texts or whether it actually applies to prophetic literature as well. With regard to idiolect, it must be considered to what extent the accumulation in parts of Isaiah could also be explained as idiolect due to its distribution throughout the Bible. In other words, based on its distribution in other biblical books, consider whether an alternative explanation for the feature is equally plausible. If, for example, a feature occurs only in Isaiah 1-39 and Amos, it is just as possible that it is due to the personal style of the two authors and does not necessarily indicate that they wrote at the same time. Only when several books from the same period frequently use a word or construction is a chronological explanation obvious.

3. Conclusion for Isaiah and outlook for linguistic dating

3.1. Linguistic dating of Isaiah

Although I remain methodologically cautious, my analysis suggests that the cumulative linguistic evidence aligns most coherently with a pre-exilic dating of Isaiah 40-66. This conclusion is not absolute; it depends on clearly stated assumptions about the dating of other biblical books. Nevertheless, when the strength, distribution, and possible alternative explanations for each linguistic feature are assessed together, a pre-exilic profile introduces far fewer difficulties than an exilic or post-exilic one. In fact, a post-exilic dating would require such extensive redating of other books that the traditional CBH/LBH distinction becomes unstable. For these reasons, a pre-exilic classification emerges as the linguistically most consistent model, even as I remain open to other outcomes.

3.2. Outlook for linguistic dating

What does this mean for the future of linguistic dating? In my research, I came to the conclusion that previous work has often been methodologically inconsistent or insufficiently rigorous, perhaps because people wanted to obtain very good or very consistent linguistic results. Nevertheless, in my view, linguistic dating has a future if the method is refined and the work is carried out thoroughly. It is essential, however, to remain open to all outcomes – including the possibility that no distinct chronolects can be established.

To better ensure this in the future, three methodological steps are very important: (1) The assumptions must be clearly stated, and it is important to review afterwards which assumptions and dates shift the linguistic results in which way. This allows us to consider how the “best” result is achieved purely linguistically. (2) It is important to critically examine the significance and strength of the characteristics and then classify them in a differentiated manner – not every characteristic is equally significant. If only two weak characteristics speak for a particular era, this must be dealt with differently than if there are two very strong characteristics that can hardly be explained in any other way. And (3) alternative explanations should be considered and weighed up for each feature. Could the feature also be explained by archaism, updating, recorded textual tradition, genre dependence, dialect, sociolect or idiolect? Once each feature has been classified, we can ultimately consider whether the majority of the features examined can be better explained in ways other than chronolect.

I hope that linguistic dating will not be discarded simply because of its past difficulties. When grounded in sound methodology, linguistic dating can and should continue to play a valuable role. It may well yield completely new results in the future. A unanimous consensus will likely remain elusive – as it so often does in human inquiry – on how Biblical Hebrew developed and how Biblical Hebrew can be used to date biblical books. Nevertheless, scholars should continue to reflect on how linguistic data can inform their models and dating hypotheses.

[1] Samuel Johannes Koser, Linguistic dating und das Jesaja-Buch: eine Untersuchung der sprachlichen Entwicklung des Hebräischen im Jesaja-Buch sowie ihre Auswirkung auf die Datierung des Buches und auf die Verwendung des Linguistic Dating im Allgemeinen. Doctoral thesis (2024), https://theoluniv.ub.rug.nl/712/.

[2] See Mark F. Rooker, “Dating Isaiah 40-66: What Does the Linguistic Evidence Say?,” Westminster Theological Journal 58/2 (1996): 304-312.

[3] See Shalom M. Paul, “Signs of Late Biblical Hebrew in Isaiah 40-66,” in Diachrony in Biblical Hebrew, ed. Cynthia Miller-Naudé und Ziony Zevit (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2012), 293-299.

[4] See Christopher B. Hays, “Linguistic Dating of Hebrew Prophetic Texts: A Quantitative Approach with Special Attention to Isaiah 24-27,” in The History of Isaiah, ed. Jacob Stromberg und J. Todd Hibbard (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2021), 69-114.

[5] See chapter 3 of my dissertation.

[6] See chapter 4.1. of my dissertation.

[7] See Rooker, “Dating Isaiah,” 310f.

[8] Isa 43:9; 49:5; 52:12; 57:1 2x; 58:8; 60:20; 62:9 (אסף) and Isa 40:11; 43:6, 9; 44:11; 45:20; 48:14; 49:18; 54:7; 56:8 3x; 60:4, 7; 62:9; 66:18 (קבץ).

[9] Isa 28:20; Esth 4:16; Neh 12:44; 1 Chr 22:2; Ezek 22:21; 39:28; Pss 33:7; 147:2; Eccl 2:8, 26; 3:5. Kanas (כנשׁ) is also found in this slightly altered spelling in Aramaic in Daniel.

[10] Ezra 7:28; 8:15; 10:1, 7, 9; Neh 1:9; 4:14; 5:16; 7:5; 13:11; 1 Chr 11:1; 13:2; 16:35; 2 Chr 13:7; 15:9, 10; 18:5; 20:4; 23:2; 24:5 2x; 25:5; 32:4, 6; Esth 2:3, 8, 19; Zech 10:8, 10.

[11] Ezra 3:1; 9:4, Neh 8:1, 13; 9:1; 12:28; 1 Chr 11:13; 15:4; 19:7, 17; 23:2; 2 Chr 1:14; 12:5; 24:11; 28:24; 29:4, 15, 20; 30:3, 13; 34:9, 28 2x, 29; Dan 11:10; Zech 12:3; 14:2, 14; Ezek 11:17; 24:4; 29:5; 34:29; 38:12; 39:17.

[12] See Hays, “Linguistic,” 90.

[13] Esth 4:14; 6:13; Dan 10:3; 11:10, 13; 1 Chr 4:10; 11:9; 21:17, 24; 2 Chr 18:27; 32:13.

[14] 1 Chr 11:9 – 2 Sam 5:10; 1 Chr 21:24 – 2 Sam 24:24; 2 Chr 18:27 – 1 Kgs 22:28. In another passage, a different verb is used, but also the infinitive absolute as in the parallel text (2 Chr 21:13 – 2 Kgs 18:33).

[15] Logos Bible Software.

[16] Zech 6:15; 7:5; 8:21; 11:17 2x; 12:3.

[17] Isa 6:9 2x; 19:22; 22:7, 17, 18; 24:3, 19; 24:20; 28:28; 30:19; 35:2; 36:15; 40:30; 48:8; 50:2; 54:15; 55:2; 56:3; 59:11; 60:12; 61:10.

[18] Ezek 1:3; 3:18, 21; 14:3; 16:4; 17:10; 18:9, 13, 17, 19, 21, 23, 28; 20:32; 21:31; 25:12; 28:9; 30:16; 31:11; 33:8, 13, 14, 15, 16; 44:20

[19] See Hays, “Linguistic,” 106.

[20] Isa 3:9; 6:7; 27:9; 30:1 and Isa 40:2; 43:24, 25; 44:2; 58:1; 59:2, 12.

[21] Logos Bible Software.

Article Comments

I think we largely agree: 1…

I think we largely agree:

1. If Isaiah 40-66 is dated post-exilic (or exilic), this raises linguistic difficulties for the CBH/LBH model.

2. If Isaiah 40-66 is dated pre-exilic, this can be better reconciled with the CBH/LBH model. However, this is only the case if some other books are also dated to the pre-exilic period (such as Zephaniah, Job, or some of the Psalms). If these are dated to the post-exilic period, a pre-exilic dating of Isaiah also presents some difficulties from a linguistic point of view.

3. I also agree with your comments on TBH: specific characteristics must be identified for TBH if characteristics are to be considered indicative of this period.

What could provide possible explanations for CBH-features if Isa 40-66 is dated to the post-exilic period? In my study, I evaluated each characteristic examined in Isaiah in terms of how easily it could be archaized or imitated. In addition, based on the distribution, I considered whether the inclusion of older text passages is plausible. In my opinion, neither of these approaches proved to be a plausible solution for Isa 40-66: some of the criteria are very difficult to archaize, and the features are distributed in such a way that it does not appear that a text block with older features has been included. (See 4.3.5. in my dissertation.)

Two questions arise that I would like to consider further:

- Would a relatively uniform linguistic system of CBH and LBH possibly emerge if we follow the more traditional dating?

- Are there alternative explanations if we assume that Isa 40-66 is post-exilic and CBH and LBH cannot be represented in this way?

Thank you for your…

Thank you for your engagement. Let me restate a few basic methodological issues that underlie my earlier comment, because they are essential for understanding why the linguistic–chronological model you are using is problematic.

1. Linguistic dating of biblical texts is intrinsically circular. Historical-linguistic analysis can only operate after the texts in question have been dated on independent literary-historical grounds. Otherwise, one first assigns a date to a book on literary or theological assumptions, and then uses those same assumptions to decide which linguistic features are “early” or “late.” This kind of literary–linguistic circularity is why traditional CBH/LBH chronologies appear uniform and coherent—because they were constructed that way in the first place.

2. Biblical books were not single-moment compositions. Dating an entire book to a single period is anachronistic. Hebrew Bible literature typically grew over long periods and went through multiple stages of redaction and transmission. Because the texts are so heavily edited, they simply do not resemble the relatively stable corpora on which normal historical linguistics usually operates. This means that the expectations of a uniform “CBH” or “LBH” linguistic system projected onto whole books do not match what we know about how these texts developed.

3. Linguistic features cannot be assigned absolute dates without external controls. Before any linguistic analysis can be chronological, there must be non-linguistic reasons to place a text (or a layer of a text) in a particular period. This is standard historical-linguistic procedure in every other field. With the Hebrew Bible, where textual growth and transmission demonstrably altered language over time, the need for prior literary dating is even more crucial.

4. Alternative explanations for mixed linguistic profiles are well known. You ask whether one could obtain a relatively uniform CBH/LBH system by assuming more traditional dates. Indeed, if one dates texts as desired and reasons in a closed circle, a tidy system naturally results. But there are well established alternative explanations for the distribution of features: textual growth, editorial revision, scribal updating, dialectal and stylistic variation, and demonstrable linguistic change during transmission. These factors account for the mixture of so-called “earlier” and “later” features far more adequately than rigid CBH/LBH typologies.

5. The wider literary and historical context must be considered. For texts such as Isaiah 40-66, the explicit references to post-exilic realities (e.g., Cyrus) already provide independent literary-historical reasons for placing these chapters in the Persian period. Linguistic features then need to be evaluated in light of that context, not used to override it.

In short, my point is not that linguistic analysis is useless; rather, it must be applied within a sound literary-historical framework and with full awareness of the complex, multi-stage formation and transmission of biblical books. Without these controls, linguistic conclusions rest on circular premises and cannot bear chronological weight.

I hope this clarifies why the traditional CBH/LBH chronological model is not methodologically viable and why your objections do not actually challenge the core issues at stake.

Thank you for your reply. I…

Thank you for your reply. I am not sure if my methodological improvements have been correctly understood in some respects.

Regarding point 1, I agree that linguistic dating faces the challenge of circularity. That is why I collected as many characteristics as possible, to see if I could produce the most coherent picture possible using a system. This is not proof, but an indication that this 'dating model' aligns relatively well with the linguistic findings.

Regarding point 2, I cannot agree with the general thesis that not a single book was composed at a single moment in time. This is clearly the case with many books, as stated in the texts themselves. For example, the historical books, such as Kings, Samuel and Proverbs, are clearly the work of multiple authors. With other books, however, it is controversial and open to debate how much can be attributed to a single author. In the case of the Book of Isaiah, for example, there are minimalists and maximalists: some attribute the entire book, or almost the entire book, to the pre-exilic prophet Isaiah. Others attribute nothing or almost nothing to this prophet.

However, this is precisely what I investigated methodically in my dissertation. I tested the extent to which the linguistic features could be explained by assuming multiple revisions or compilation of different sections. My assumption was that individual blocks in Isaiah 40–66, for example, contain more CBH because earlier texts were simply incorporated. However, this has not been confirmed. The CBH features in Isaiah 40–66 are completely irregular and widely scattered. At the very least, this is difficult to reconcile with text blocks from different periods.

Regarding point 3: that's correct – it is not possible to assign absolute dates without certain prerequisites. Any linguistic dating is based on assumptions about how other books (whether biblical or non-biblical) are dated. However, based on these assumptions, it is certainly possible to assign absolute dates, or, as I suggest, to retrospectively consider in which cases a uniform system emerges.

Re 4:

As a scholar, I believe that one should always be critical and question even established models. This is why I have tested a variety of models (literary-critical, editorial-critical, traditional and synchronous) in my work, to see how easily and to what extent the linguistic features identified can be incorporated into Isaiah. This is, of course, possible with every model. With some, however, it is more challenging than with others.

I know this does not correspond with the mainstream view today, but I was surprised at how few linguistic problems the traditional dating of the book presents with regard to Isaiah alone.

Your argument is: 'If one dates texts as desired and reasons in a closed circle, a tidy system naturally results.'

But that was not the case with Isaiah. I expected to find LBH characteristics in Isaiah 40–66 (i.e. linguistic features that also occur especially in the undisputed LBH books, such as Ezra, Nehemiah, Daniel, Esther, Chronicles, Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi). But that was not the case at all! To me, this was an exciting indication that the 'traditional' dating methods are not completely at odds with the language, as is sometimes claimed, but can in fact be combined with CBH/LBH. This is not purely circular reasoning, because the linguistic features that appear in the LBH books I listed could well support the LBH dating of Isaiah 40–66.

Re 5:

The language can never provide clues for a single name or individual verses. Therefore, the only conclusion that can be drawn is that the language is consistent with a broad pre-exilic dating of Isaiah 40–66. Dating most of it to the post-exilic period would raise a few more linguistic problems. The language says nothing about whether individual verses or the name Cyrus, for example, were added later, but of course this can still be assumed.

And one question remains: What is a good alternative explanation for the linguistic features and their distribution in Isaiah? I am open to specific suggestions =)

Thank you for the further…

Thank you for the further explanations. For me, the central issue is that linguistic dating cannot be reconciled with mainstream literary-critical scholarship: named authorship in biblical books is a discourse convention rather than historical evidence, and the MT reflects a long process of growth, revision, and linguistic updating. The distribution of linguistic features in Isaiah—both salient and non-salient—is readily explained as the cumulative result of successive authors, editors, and scribes over centuries rather than the product of a single compositional moment. I’ve appreciated the exchange, and this seems a good place to leave the discussion.

Whether "this seems a good…

Whether "this seems a good place to leave the discussion" or not, may be up to others, perhaps outside of this thread, but I will merely note that neither confident title claim is, as far as I know, generally accepted. The two, bold, titles:

"Refining Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts: Methodological Considerations for Future Use"

and

"Isn’t It Time to Break Up with Linguistic Dating? Rethinking Hornkohl’s Method—and What Comes Next"

For what little it may or may not be worth, with due respect, neither future/next thing prediction fully persuaded me.

Actually, I would disagree…

Actually, I would disagree with your description of what is “generally accepted.” One of our central points—both in the earlier article and in our broader work—is that the approach which elevates linguistic dating as the decisive criterion is not broadly embraced, either within biblical studies as a whole or across other historical disciplines. As we wrote:

“Continuing the theme of integration highlighted above, this is a subject we have explored and emphasized for decades. Yet many scholars remain entrenched in the conventional linguistic-dating paradigm, often overlooking the need for an approach that fully integrates historical, cultural, social, literary, textual, linguistic, and conceptual dimensions when tracing the compositional history of the Hebrew Bible.”

The issue is not that linguistic dating is the consensus in biblical studies — it isn’t. Rather, it persists as a significant and influential minority approach, one that continues to shape debate and methodology, despite its methodological limitations. And this stands in contrast with other historical disciplines, where linguistic evidence is generally treated as one strand among many, not as the primary or determinative factor. In that broader context, the insistence on linguistic priority appears even more anomalous.

As far as I know, in…

As far as I know, in biblical studies, "linguistic evidence is generally treated as one strand among many." Now. Robert Rezetko, you seem to be fighting one minority view with an opposite minority view. For me, on this, neither extreme, thank you.

It seems to me that an…

It seems to me that an approach seeking to integrate linguistic evidence with other dimensions of inquiry is not “extreme” at all, but rather balanced and moderate. We are hardly advocating an all-or-nothing stance—whether “all language” or “no language.”

Wouldn't it be helpful to…

Wouldn't it be helpful to discuss specific arguments?

In the end, it doesn't matter what a minority or majority currently thinks or what is extreme or not. As scientists, we are searching for truth and weighing up arguments. Sometimes even new arguments against a previous majority :-)

And based on my study, the result seems to me to be:

- Either CBH/LBH cannot be attributed to post-exilic and pre-exilic Hebrew – because several widespread CBH characteristics appear in Isa 40-66. If Isa 40-66 is dated to the post-exilic period, one must therefore justify and say that CBH could still be written after the exile (which is entirely possible). But then CBH and LBH in general simply do not indicate a chronological classification.

- Or one would have to reconsider whether a pre-exilic dating (of most of Isa 40-66 – smaller parts could of course have been added later – the language does not say anything about this) could also be a possibility.

Or are there objections to this? Both are possible, of course – one must consider which makes more sense in the overall picture. With the first solution, the question remains open for me: Is it plausible that there was no traceable chronological linguistic development? Or is there another option and linguistic features that trace a completely different development? So, for certain dates of the books in the Old Testament, is it possible to trace such a uniform linguistic development and linguistic features that are clearly distributed across different eras in other ways? Otherwise, what remains for me is the interesting finding that traditional dating of Isa 40-66 also yields a surprisingly coherent linguistic picture, for which I, at least, have not yet found a more uniform system.

I guess I would incline to…

I guess I would incline to the first of the two options you offer. However, I think that are other options, such as that the language of the Masoretic Text of Isaiah is not evidence of the language used by original authors of the various parts of Isaiah. The language of the biblical books in general was subject to widespread updating in scribal transmission, as we demonstrated in detail in Historical Linguistics and Biblical Hebrew.

Yes, that is one possibility…

Yes, that is one possibility. It does not seem obvious to me in Isaiah. I weighed up each individual feature and considered how likely an update or archaicisation would be. Several of the features in Isaiah 40-66 are complex in terms of grammar and syntax and are therefore very difficult (or almost impossible) to revise in an update. But that doesn't mean it's impossible. It just makes the option less likely.

I agree with your conclusion that the traditional distinction between Classical and Late Biblical Hebrew becomes unstable if Isaiah 40-66 is dated to the post-exilic period. The language of Isaiah 40-66 is indeed “anchored well” (Hurvitz) in Classical Biblical Hebrew. Where you and I differ is that I, with Young, Ehrensvärd, and others, regard the CBH/LBH dichotomy itself as already theoretically and methodologically unstable.

With respect to II(-III) Isaiah, I consider this material -- on the basis of historical, theological, and other criteria -- to have been composed in the exilic/post-exilic period, in line with the critical consensus. Accordingly, I view its language as a prime specimen of exilic/post-exilic Classical Biblical Hebrew. (See further my unpublished discussion here: https://www.academia.edu/25885221/2016k_Rezetko_Response_to_Rooker_Char….)

All of this, however, raises uncomfortable questions that cut in both directions and run counter to various forms of scholarly consensus. Scholars have long recognized the dilemma, and more recently some have attempted to account for the language of Isaiah 40-66 by classifying it as “Transitional Biblical Hebrew.” Yet, as you have hinted, this explanation is also unsatisfactory. Moreover, the very notions of Transitional Biblical Hebrew and “transitional language” more generally are themselves deeply problematic, both theoretically and empirically. (See further https://www.sbl-site.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/9781628370461_OA.pdf, esp. pp. 395-402; https://jhsonline.org/index.php/jhs/article/view/29350/21370, esp. pp. 29-38.)