By Morag M. Kersel

Department of Anthropology

DePaul University

October 2011

In October of 2002, it was announced that an Aramaic inscription (Ya’akov son of Yoseph, the brother of Yeshua) on nondescript limestone box, looted from a cave in Jerusalem and held in the private collection of long-time collector Oded Golan, might be the earliest known archaeological reference to Jesus. As news of the inscription was released, the details of the ossuary’s (secondary burial bone box) archaeological context were sketchy at best, calling into question the authenticity of the find for many scholars. At the initial press conference announcing the existence of the inscribed ossuary, Hershel Shanks, editor of Biblical Archaeological Review, stated that the owner purchased the ossuary in the early 1990s from an antiquities dealer in Jerusalem’s Old City for between US $200 and US $700. Later it was claimed that the piece was purchased in the 1970s for around $200. This recanting of the original date may seem insignificant, but the date of purchase is central to determining ownership – if anyone can really own the past. If in fact the ossuary was acquired in the early 1990s – just over twenty years ago – without proper documentation, it belongs to the State of Israel rather than Golan. The Antiquities Law 5738-1978 of Israel established a law, which among other things vests ownership of cultural heritage found after the benchmark date of 1978 to the State of Israel. At the same time, the law established a legal trade in antiquities: it is legal to buy and sell artifacts from collections (private, museums and existing shop inventories) established before the Antiquities Law of 1978. After that date, all newly discovered antiquities are the property of the state.

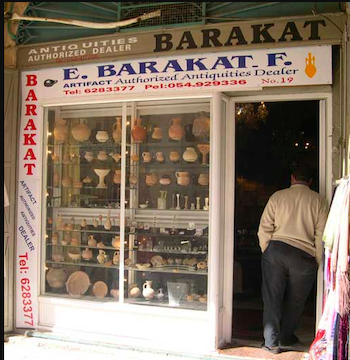

Every day in the Old City of Jerusalem or Tel Aviv or Jaffa it is possible to buy an artifact and take it home, even if home is a third floor walk up in New York. Tomorrow any one of us could go into a licensed shop in the Old City and buy an ossuary, with or without an inscription. The legal trade in antiquities in Israel is a legacy of earlier Ottoman legislation that made provisions for the legal movement of archaeological material within the Empire. In 1948, in order to maintain a sense of normalcy, the newly established State of Israel adopted the antiquities ordinances of the British Mandate, which also supported a trade. Promoted and endorsed by luminaries like Teddy Kolleck and Moshe Dayan, the legalized trade became enshrined in the antiquities law enacted in 1978. Law makers and politicians like Kolleck and Dayan were avid collectors of Holy Land material and they, along with the Palestinian families who had been in the antiquities business for generations, had a vested interest in wanting the trade to continue. These lobbying efforts and influential elements resulted in the situation today where a tourist can enter a licensed shop, buy an artifact and leave with an export license and even a certificate of authenticity (which may or may not be worth the paper on which it is printed). But where do the ossuaries, oil lamps, and oinochoe (wine jugs) for sale in the streets of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv come from?

For the last ten years, I have attempted to answer just that question – how artifacts go from the ground to the consumer in the Holy Land. My PhD research, collected during a year in Jerusalem (2003-2004), led me to conclude that illegally excavated and stolen material was entering the legal market at a regular rate. Many of the artifacts for sale in the legal market have falsified records of ownership and archaeological findspot. Looters illegally excavated items, which enter well-organized networks of trade allowing them to be laundered along the way, only to be sold to unsuspecting tourists and collectors with a clean bill of sale in a state sanctioned shop.

Ossuary for Sale in

the Old City,

Jerusalem

When Oded Golan inquired about provenience (archaeological findspot) of the “James Ossuary,” the dealer stated that it came from Silwan, a Jerusalem neighborhood dotted with tombs from the first century CE. The tradition of ossuaries has been archaeologically documented for this period in the Silwan area, but because the “James Ossuary” was purchased on the market, we will never know its true archaeological context or whether there were associated finds that would support the claims of authenticity and refute the allegations of forgery. For many scholars, the debate will never be resolved in a satisfactory manner. Research from the Middle East and other areas of the world amply illustrates the connection between the demand for archaeological material and the looting of archaeological sites to meet growing demand. I use the “James Ossuary” by way of illustration not because it might be the earliest tangible archaeological evidence for Jesus of Nazareth – but to demonstrate the destructive influence that the looting of archaeological sites and the subsequent trade in antiquities, whether legal or illegal, has on our collective knowledge of the past.

Comments (8)

If the "James" ossuary had been properly excavated by trained archaeologists, they would have been able to present the evidence from the excavation. That evidence might have indicated whether the claim that the ossuary actually once held the bones of James the brother of Jesus was true or not. Because it was simply taken from the ground without any records, we will never know. So much for the illegal (and legal) trade in antiquities! Thanks for the powerful essay!

#1 - Paul Flesher - 10/19/2011 - 21:51

It is not true that we can not know the provenance of the ossuary. When the tomb in Talpiot, Jerusalem, was excavated in 1980, there were 10 ossuaries and one "came up missing." The elemental analysis of the James ossuary and the nine that the IAA didn't lose matched perfectly. It is a scientific surety that the James ossuary came from Talpiot. The author must not comprehend the science which so often is the case in archeology.

#2 - Eliyahu Konn - 10/21/2011 - 00:47

on the criticism of the author; cf what joe zias notes, especially in regards to a photo Oded Golan produced: http://www.joezias.com/tomb.html

#3 - david meadows - 10/22/2011 - 16:17

@ Comment No.2: "..a scientific surety that the James ossuary came from Talpiot." This statement is either intentionally deceptive, or indicates a poor understanding of science. Similarity of elemental analyses of these ossuaries is unsurprising, as we would expect them to be made from the same rock formations. In no way does this prove that the ossuaries came from the same tomb. There is, however, one way to prove that: archaeological excavation with documentation (notes, photos, drawings, etc). Without this, you have a looted artifact.

#4 - Yorke M Rowan - 10/23/2011 - 18:11

As for comment #4 on the analysis of the patina on the James ossuary and the possible connection to the Talpiot tomb, see the following, "The Connection of the James Ossuary to the Talpiot (Jesus Family Tomb)" Ossuaries bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/JOT

Editors

#5 - Editors - 10/23/2011 - 21:12

Yes you are right we all own the past.

But I am sure that after 10 years of your research you will agree

with the sad knowledge that since 1967, 90-95% of the small artifacts discovered in Israel including Judea and Shomron are unprovenanced (looted) and sold in the markets to collectors and museums.

Do you, as well as commentator #4 want to neglect 90% of the history of the people that lived in Israel- Canaan? Discarding gigantic amount of significant artifacts? Even the IAA and their allies are publishing looted artifacts (e.g. the ossuary of ‘Miriam Daughter of Yeshua Son of Caiaphas).

Do you know that most of the "big" discoveries came from looting and are the exhibits of all the Museums all over the world including the DSS?

Geo-bio-chemical scientific evidences strengthen the contention that the inscription of the James ossuary is authentic. Needless to say that philological and epigraphical studies on James Ossuary also indicate an authentic inscription.

Amnon Rosenfeld (geologist; archaeometrist)

Geological Survey of Israel

Jerusalem, Israel

#6 - Amnon Rosenfeld - 10/23/2011 - 23:08

In my opinion the author has missed the whole point of the court case. The question was whether or not the inscription was forged, as the antiquity authorities had originally claimed. The basis for their claims has clearly been shown to be completely flawed and unscientific.

#7 - Dave Lightbody - 10/25/2011 - 11:38

In response to commenter #7, I think you miss the author's main point. The article draws on the example of the court case--not, to provide a case summary thereof, but--to link a very public case to the issues arising from her "less public" doctoral research, which need airing. It goes without saying that the court case is limited in its scope to specific legal claims at issue. Then again, not having read the judicial decision, I wonder whether any obiter plainly intersect with the larger issues entailed by the author's research? Anyone?

#8 - Camilla Von - 10/25/2011 - 17:32