A discussion of the importance of the Israelite house architecture in understanding women's social, economic and religious activities.

By Elizabeth Willett

Hebrew Bible translation consultant

SIL International

April 2003

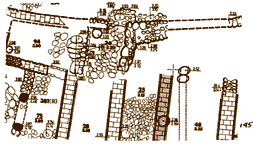

Knowledge of the architectural plan of Israelite houses provides the context for a discussion of women’s social, economic, and religious activities within its ambience. The usual Israelite house consisted of three long rooms separated by pillars and a rear broadroom. The side rooms were often cobbled or paved and the central room served as a courtyard. The massiveness of the pillars and remains of stairways indicate that some Israelite houses included second stories or work-worthy roofs. While Stager (1985) and Holladay (1992, 1997) suggest that families lived upstairs due to cramped ground-floor rooms and ethnographic parallels, others like Herzog (1997) hold that at sites like Beer-sheba the rear broadroom served as the family bedroom, while an extra front room facing the street functioned as kitchen.

Ethnographic and historical studies on the division of labor by gender demonstrate that men’s activities characteristically center on food production and community leadership, while women tend to manage the household economy, including food storage and preparation. Because the household is woman’s domain, she manages directly or indirectly all of its contents. However, items connected with processes of food preparation and storage—grinding stones, ovens, cooking pots, storage jars, and food particles—remain particularly visible in the archaeological record.

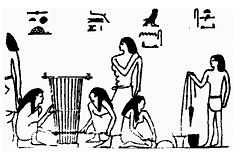

In the subsistence agricultural setting of early Israel, when there was little craft specialization, women spun thread and wove textiles for their family households. Even in industrial contexts weavers and spinners were always women. Biblical descriptions like Proverbs 31 and 2 Kgs 23 attest that Israelite women assumed the responsibility of weaving textiles and producing clothing for their families and deities. Ancient Near Eastern texts, stone reliefs, and paintings also portray women as spinners and weavers.

In the subsistence agricultural setting of early Israel, when there was little craft specialization, women spun thread and wove textiles for their family households. Even in industrial contexts weavers and spinners were always women. Biblical descriptions like Proverbs 31 and 2 Kgs 23 attest that Israelite women assumed the responsibility of weaving textiles and producing clothing for their families and deities. Ancient Near Eastern texts, stone reliefs, and paintings also portray women as spinners and weavers.

Needles, loom weights, food storage vessels, cooking pots, dishes, and food remains define women’s work areas in Israelite houses. These feminine implements frequently occur together with incense altars and female figurines in house rooms and courtyards. Often jewelry and accessories that Israelite women used to deflect evil forces accompany their household weaving and cooking tools. The Israelite period houses at Lachish, Tell Masos, Tell el-Far'ah, Beer-sheba, and Tell Halif provide examples of cultic artifacts and furniture Israelite women employed in household rituals.

Needles, loom weights, food storage vessels, cooking pots, dishes, and food remains define women’s work areas in Israelite houses. These feminine implements frequently occur together with incense altars and female figurines in house rooms and courtyards. Often jewelry and accessories that Israelite women used to deflect evil forces accompany their household weaving and cooking tools. The Israelite period houses at Lachish, Tell Masos, Tell el-Far'ah, Beer-sheba, and Tell Halif provide examples of cultic artifacts and furniture Israelite women employed in household rituals.

Women’s Protection at Lachish

The most interesting finds from houses along the street from the city gate and south of the palace in eighth century BCE Iron Age Lachish (Tufnell 1953) consisted of the female figurines and jewelry that accompanied women’s household items. Each dwelling contained at least one piece of jewelry, most of it related to apotropaic function through Egyptian mythology and ethnographic parallels. The contents of House 1008 included a female figurine with a draped headdress and an imitation cowrie amulet, along with clay spindle whorls, burnt fibers, and cooking and storage vessels. Modern Middle Eastern cultures use cowrie shells as amulets to deflect the evil eye from infants because the shells look like eyes. House 1002 held another eye amulet—a bone sacred eye scarabaeid—as well as lamps and women’s weaving and cooking tools. In addition to a loom beam, loom weights, and a dyeing vat, House 1003 had a lamp, a chalice, and cooking pots, together with a blue faience bead. Women wore blue and green stones to avert evil, especially the evil eye.

Besides cooking pots, House 1032 produced six beads, one of them gold, a faience Nefertum amulet, a carnelian spacer and a shell fragment, also apotropaic devices. People regularly choose red as a color for apotropaic motifs because they believe it deflects demons and evil eyes. In addition, they think demons fear jewelry made of gold or other shiny metals. Locus 1031 showed two more eye amulets Israelite women wore to protect themselves and their newborn infants—a blue faience imitation cowrie amulet and a bone pendant with ring-and-dot designs. In Locus 1033 lay a hand-modeled goddess head from a vessel and two Egyptian Twenty-sixth to Twenty-second Dynasty scarabs. These rooms in eighth century BCE Lachish houses south of the palace confirm the importance of magic jewelry and female figurines in the everyday lifestyle of ancient Israelite women.

Many of the houses or shops along Road 1087 leading into the town from the gate are only partially excavated, however what is reported for them is similar to what we know about the houses south of the palace. Each group of rooms had at least one figurine or amulet. Along with conventional household goods like loom weights, a lamp, a cooking pot, bowls, jars, jugs, a ploughshare, and an ox goad, House 1089 contained two bone fan-handles pierced for suspension, one with circle and dot designs, and a steatite scarab. In House 1078 lay a figurine with a curled wig and pointed cap, a lamp, a cooking pot, and storage jars, and in House 1080 a pendant, a cooking pot, and kitchen bowls and jars. In addition to a saddle quern and grinders, lamps, a cooking pot, bowls, juglets, and jars, House 1040 presented a green faience quadruple divine eye amulet and a bone disk pierced for suspension. Similarly, House 1043 had a bone disk with circle designs, pierced for suspension, accompanied by evidence of women’s cooking activity in the form of burnt olive stones and cooking vessels.

The bone disks pierced for suspension from a necklace or possibly from the house doorway, as well as the bone pendants and fan handles with ring-and-dot designs, the green faience quadruple eye, and the sacred eye scarabaeid, all manifest Israelite women’s concern for protecting themselves and their children from evil eye and the child-stealing demons. The beads, faience deity amulets, and figurines come from feminine weaving and cooking contexts. They illustrate the religious jewelry Israelite women wore and the images they placed in their homes to protect themselves and their children. Modern Middle Eastern women combat the same fears about the evil eye and child-stealing demons with similar eye amulets—blue beads, cowrie shells, and shiny metal objects.

The bone disks pierced for suspension from a necklace or possibly from the house doorway, as well as the bone pendants and fan handles with ring-and-dot designs, the green faience quadruple eye, and the sacred eye scarabaeid, all manifest Israelite women’s concern for protecting themselves and their children from evil eye and the child-stealing demons. The beads, faience deity amulets, and figurines come from feminine weaving and cooking contexts. They illustrate the religious jewelry Israelite women wore and the images they placed in their homes to protect themselves and their children. Modern Middle Eastern women combat the same fears about the evil eye and child-stealing demons with similar eye amulets—blue beads, cowrie shells, and shiny metal objects.

Tell Masos

The structures and artifacts in several dwellings at Tell Masos suggest that early Israelites maintained household shrines. The presence in Room 307 of the four figurines typical of votives deposited in the Hathor temple at Timna demonstrates that the residents of House 314 depended on an established relationship with a personal protective goddess whom they worshiped in their home in addition to or instead of in a public sanctuary. They probably used the hearth and mud brick structure with ash residue, as well as the courtyard bench, for metalworking and associated religious rituals invoking the family goddess. Room 331 which residents entered near the courtyard bench held three incense burners, three lamps, a bead, a large number of shells from the Red Sea, and a Canaanite-Phoenician style ivory lion head. The lion symbolized and accompanied the powerful protector goddesses of the Egypto-Canaanite pantheon, so its presence with the incense burners and lamps in Room 331 implies that a woman with a newborn child slept there and protected herself and her newborn with shells and beads and by burning oil and incense to welcome the goddess and to deflect the presence of jealous spirits.

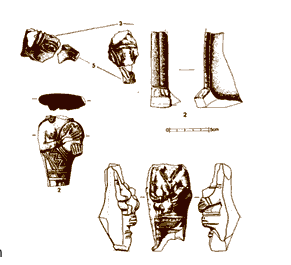

The conspicuous benches, careful plastering, and body sherd paneling suggest that Room 169 in House 167 functioned as a shrine because plastered and decorated walls with benches around them are defining architectural features of domestic cult rooms in the southern Levant. Several artifacts discovered in the room itself and in and around House 167 hint at luxury votive offerings, and a bone scarabaeid carved with animals and a limestone lion head are connected with the goddess Asherah. At the center of House 42’s outer court next to an ash pit stands a .5 m. high structure with an attached bench. No accompanying artifacts indicate that residents employed the structure in technological activities, and it resembles offering podiums that furnish cult areas in the Levant. A cooking pit, cookpot, jugs, and bowls indicate that a woman prepared food in the area near the elevated structure. The bone amulet with ring-and-dot designs, the chalice fragment, and the decorated stand suggest women’s household religious ritual to deflect demonic forces.

Throughout the late seventh to early sixth century BCE Area G rooms at Tell Masos excavators found female and animal figurines, lamps, and a furniture model among women’s textile production implements such as spindle whorls, needles, and pins, as well as food storage and preparation vessels like cooking pots, bowls, storage jars, and kraters. The presence of ritual artifacts in the environs of women’s implements illustrates the importance of household religion to Israelite women’s daily life.

Tell el-Far'ah

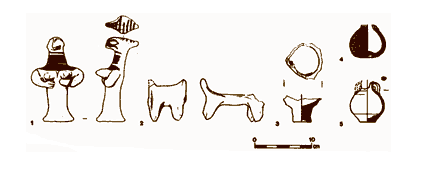

Most of the Israelite dwellings from the tenth century Level 7b at Tell el-Far'ah, biblical Tirzah, included either a female or an animal figurine in their household commodities. Horse figurines, often accompanied by arrowheads, came from several buildings in the southern section of the residential district as well as from the defense fosse and the open space facing the city gate. While the war goddess symbolism of horse figurines labels those from public find spots as amulets for military men, those from houses must have fulfilled a purpose similar to the protective figurines that guarded Mesopotamian houses (Lichty 1971; Black and Green 1992). The ivory pendant, flute-player amulet, female figurine fragment, model sanctuary, and the beads and pierced disk from Houses 187, 149B and 161 from the western edge of the settlement show that Israelites did not confine their religious thoughts and activities to public temples. The bovine heads, the cow nursing calf motif, the beads and blue jewelry plaque, the woman with tambourine figurine, and even the lamp from Houses 176, 427, and 436 represent women’s religious beliefs and rituals their wider ancient Near Eastern heritage associated with fertility and a mother’s protection. No specifically male accoutrements accompany these votive artifacts; on the other hand, items like household pottery and the spindle whorl confirm women’s interest in them.

Biblical and other ancient Hebrew texts like the Khirbet el-Kom and Kuntillet Ajrud inscriptions imply that Asherah acted as Israel’s protective goddess. Mention of Asherah occurs in the biblical context of the death of King Jereboam I’s son while he was living here at Tirzah. The prophet Ahijah informs Jereboam’s wife that her child will die and God will punish Israel because they have made “asherahs” (1 Kgs 14:15); then “Jereboam’s wife went away back to Tirzah, and as she crossed the threshold of the house, the boy died” (1 Kgs 14:17). Israelite figurines, including those in Tirzah, represented Asherah, who not only partnered with El/Yahweh in providing children, but also protected them and their mothers from infant mortality and short female life span. This provides the background against which the prophet Ahijah reprimands Jereboam’s wife for making images of Asherah and allows her child to die.

The northeastern section of the tell is particularly rich in cultic finds. In addition to House 427 where the excavators discovered bovine and female figurines, House 436 included several luxury votive objects, House 442 contained an incense burner and Cypriot bowls, and their neighboring House 440 produced a nursing female figurine, a harnessed horse head from a zoomorphic vessel, an alabaster pendant, six beads, and another female with tambourine figurine from the beaten earth floor of its courtyard near a 3 m. long stone bench, as well as a model sanctuary.

Several of the houses in Level 7 at Tell el-Far'ah have courtyard alcoves that connote niches where women repeated prayers and incantations, poured libations, and burned oil and incense to the protecting household goddess. Women’s cooking installations predominate in these courtyard areas where excavators also found fragments of female figurines, zoomorphic libation vessels, and women’s textile-producing tools. The Israelite houses from tenth century BCE Tell el-Far'ah demonstrate women’s religious agency in their households.

Several of the houses in Level 7 at Tell el-Far'ah have courtyard alcoves that connote niches where women repeated prayers and incantations, poured libations, and burned oil and incense to the protecting household goddess. Women’s cooking installations predominate in these courtyard areas where excavators also found fragments of female figurines, zoomorphic libation vessels, and women’s textile-producing tools. The Israelite houses from tenth century BCE Tell el-Far'ah demonstrate women’s religious agency in their households.

Tell Beer-sheba

The eighth century BCE Israelite houses in Tell Beer-sheba Stratum 2 provide several examples of cultic artifacts in women’s cooking, food storage, and weaving areas. Front Room 94, the site of a woman’s oven and cooking pots, held a lamp and a fragment of a zoomorphic figurine. Stationing a figurine to guard the entrance and lighting a lamp to attract the beneficent deity and deflect evil ones are rituals Near Eastern women habitually practiced.

Courtyard 36, itself a kitchen, borders both Room 94 on the north and Room 25 on the south, where excavators found a female figurine, miniature lamp, and model couch. Architectural structures that resemble offering shelves line the sides of Courtyard 36 where it adjoins these two find spots of figurines and lamps. Domestic kitchens in front rooms near the street, because they give entrance to the living and work space on the roof and to the rear bedrooms and food storage, afford natural places for household shrines that honor the deity who guards against potentially damaging evil eyes and spirits that attempt access to the house.

Courtyard 36, itself a kitchen, borders both Room 94 on the north and Room 25 on the south, where excavators found a female figurine, miniature lamp, and model couch. Architectural structures that resemble offering shelves line the sides of Courtyard 36 where it adjoins these two find spots of figurines and lamps. Domestic kitchens in front rooms near the street, because they give entrance to the living and work space on the roof and to the rear bedrooms and food storage, afford natural places for household shrines that honor the deity who guards against potentially damaging evil eyes and spirits that attempt access to the house.

A krater with horizontal loop handles labeled Ø∆H “consecrated” belongs to a front room shrine of House 76. A cosmetic stick, stone pendant, mother-of-pearl, loom weights, as well as food remains and containers mark this area as the domain the mistress of House 76 traversed on her way from her cooking and weaving area to the food storage in casemate Room 66. The room combination 44-145 contained an oven, 30 clay loom weights, a jar inscribed with lwm, cooking pots and a figurine fragment. The long central Room 48 of Building 25 contained another figurine fragment, beads, a bracelet, loom weights, a decorated amphora, a button, cooking pots, and a large number of bowls and storage jars. The women’s jewelry, textile production tools, and cooking equipment that surround the figurines in these Israelite houses affirm that women owned them and incorporated them in their household religious rituals.

The Room 25 pillar-base figurine has a flattened head and striped neck similar to the Ashdoda figurine—a combination of female figurine and offering table in which the head and chest of the goddess form the back of the throne or chair, while the seat of the chair is her lap (Dothan 1971). Similarly shaped “seated female” figurines with offering-table laps come from Assyrian Assur. The Ashdoda derives from Mycenaean black and white striped “divine nurses.” One form stands on a pillar base and supports a child; another form seats a goddess on a throne-chair with arms down to hold a child at its waist.

Model furniture that represents the lap of the child-protecting goddess appeared with figurines and incense burners in Houses 25, 808 and 430. Additional figurines occurred with lamps. These cultic artifacts from women’s work areas at Tell Beer-sheba indicate that women positioned images of the family protective goddess near vulnerable entrances to their dwellings, provided her with votive offerings, and burned incense and oil to invoke her aid.

Tell Halif (Lahav)

At Tell Halif (Lahav), the Field 4 team exposed the remains of a household shrine in Stratum 6B. Elements of the shrine mixed with ordinary household pottery in the ground floor rear broadroom of a late eighth century four-room house. On floor G8005 of the room the molded head of a female pillar-base figurine accompanied a ceramic fenestrated incense stand. The household shrine room architecture revealed two phases. Residents modified its initial purely domestic nature by blocking doorways and constructing insulating walls or offering benches to create a more sacred space in its second phase. These apparently cultic structures and artifacts occupied women’s workspace in the private Israelite house. Many household clay vessels and stone and bone utensils dominated the room. An oven outside the room, fish bones, and carbonized remains of grapes, cereals, and legumes indicate that this was a woman’s food preparation and storage area. This Israelite house shrine at Lahav affords another excellent example of an incense-burning altar and a female figurine associated with a woman’s work area.

Israelite Women and House Cult

Israelite women baked in ovens in courtyards that opened onto the street. As in other ancient Near Eastern cultures, women protected themselves from forces that attempted to attack them and their children. They placed figurines that represented and invoked protective deities in front kitchens or courtyards of their houses near doorways that provided access to the roof and interior living and work areas. For example, figurines and clearly votive vessels came from front Rooms 93, 94, and 443 and the remaining front half of House 25 including Rooms 25, 48, and 145 at Beer-sheba. Entrance Courtyards 36 at Beer-sheba, 314 and 42 at Tell Masos, and 440, 355, 327, and 436 at Tell el-Far'ah include elevated structures that may have served as offering places for house divinities. Figurines came from near most of these structures, especially at Beer-sheba and Tell el-Far'ah. For example, excavators found figurines in the same loci as alcoves or benches in Courtyards 440, 355, and 327 at Tell el-Far'ah and in loci adjoining Courtyards 436 at Tell el-Far'ah, 36 at Beer-sheba, and 314 and 42 at Tell Masos.

In many cases incense burners or lamps accompany figurines in Israelite houses to purify the house rooms from evil and to invoke protective deities. The lamps and incense burners take various forms: chalices, fenestrated clay offering stands, miniature votive lamps, normal lamps, clay models that represent the child-protecting goddess’s lap, as well as small limestone incense altars. Depending on the time period, all of these occurred in Israelite living spaces with deity figurines and women’s implements.

Overall, women managed Israelite household economies, but they were specifically responsible for food storage and preparation as well as clothing production. Women’s other major contribution consisted in childbearing and education. Figurines and incense burners in rear broadrooms protected sleeping mothers and their newborn infants from mythological flying night demons. Rear storage and sleeping rooms at Tell Masos (307, 331, and 169), Tell el-Far'ah (442) and Tell Halif (G8005) contained evidences of household cult including incense burners or elevated offering structures that invoked deities who protected women and their infants while they worked and slept. Apotropaic amulets and accessories, especially in sleeping rooms, also testify to women’s concerns with protecting their infants from child-stealing demons. For example, apotropaic jewelry accompanied incense burners and chalices in rear broadrooms of Tell Masos Houses 314 and 42 and Tell el-Far'ah House 442, and women’s food storage and preparation artifacts in several other rooms including Tell Beer-sheba casemate Rooms 63 and 66 and Courtyard 48 and Tell el-Far'ah Houses 440, 161, and 436. In each Lachish III house archaeologists found apotropaic jewelry and figurines among assortments of women’s cooking and weaving tools.

These Israelite period houses at Lachish, Tell Masos, Tell el-Far'ah, Beer-sheba, and Tell Halif reveal the cultic artifacts and furniture Israelite women employed in protective household rituals. Family shrines and neighborhood cult rooms in the ancient Near East provide parallels that help to interpret the cultic structures, artifacts, and jewelry these Israelite houses exhibit.

Elizabeth Willett has a Masters degree in linguistics from the University of North Dakota and Masters and Doctorate degrees in Near Eastern Studies with minors in the History and Culture of Ancient Israel and Near Eastern Archaeology from the University of Arizona. She is a Hebrew Bible translation consultant with SIL International.

Article Comments

Often I will read a post and…

Often I will read a post and think great post! ...

Thank you for sharing valuable information for us

Unfortunately, "Bibliography" does not appear. Could it be supplemented to see the cited literature for further information?