When English translations smooth over the objectifying language or the action verbs that imply force and coercion are involved in biblical “marriage” relationships, we have been misled. As much as I wish to support loving couples choosing to marry today, I also wish to be clear about how differently these ancient people wrote and thought about the dynamic between paired-up people in their day.

See also Marriage in the Bible: What Do the Texts Say? (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2023).

By Jennifer G. Bird, PhD

Public Biblical Scholar

JenniferGraceBird.com

May 2024

One of the more surprising aspects of this conversation about what the Bible says about marriage is the element of misleading translations. There are four verbs in the Hebrew that are used to refer to some form of pairing up. There is also a fifth kind of a category, when using the Hebrew term baal, or lord, to refer to the role that the man is to take in relation to the woman.[1] We will look at the meanings and implications of these verbs so that you can decide for yourself if the relationships in question, based on the action taken to create them, look or sound like a “marriage” does to you, today. There is also the matter of the labels that are used for men and women, in both primary testaments of the Christian Bible, to differentiate between when they are paired up from when they are not. In fact, there is no distinction!

Why does any of this matter? When we read a line or passage in the Bible that uses marriage terminology, but the original did not have such a category or use such differentiating terms, are we not being slightly misled? If the Hebrew or the Greek simply calls a couple a man and woman but the English in both cases calls them a husband and a wife, do you see how there are subtle, or even blatant, relational biases that these labels communicate to the reader? It turns out that the language we use to clarify relational statuses does matter to most people; it has an impact on what they imagine is happening in that relationship and what kinds of dynamics are at play within it.

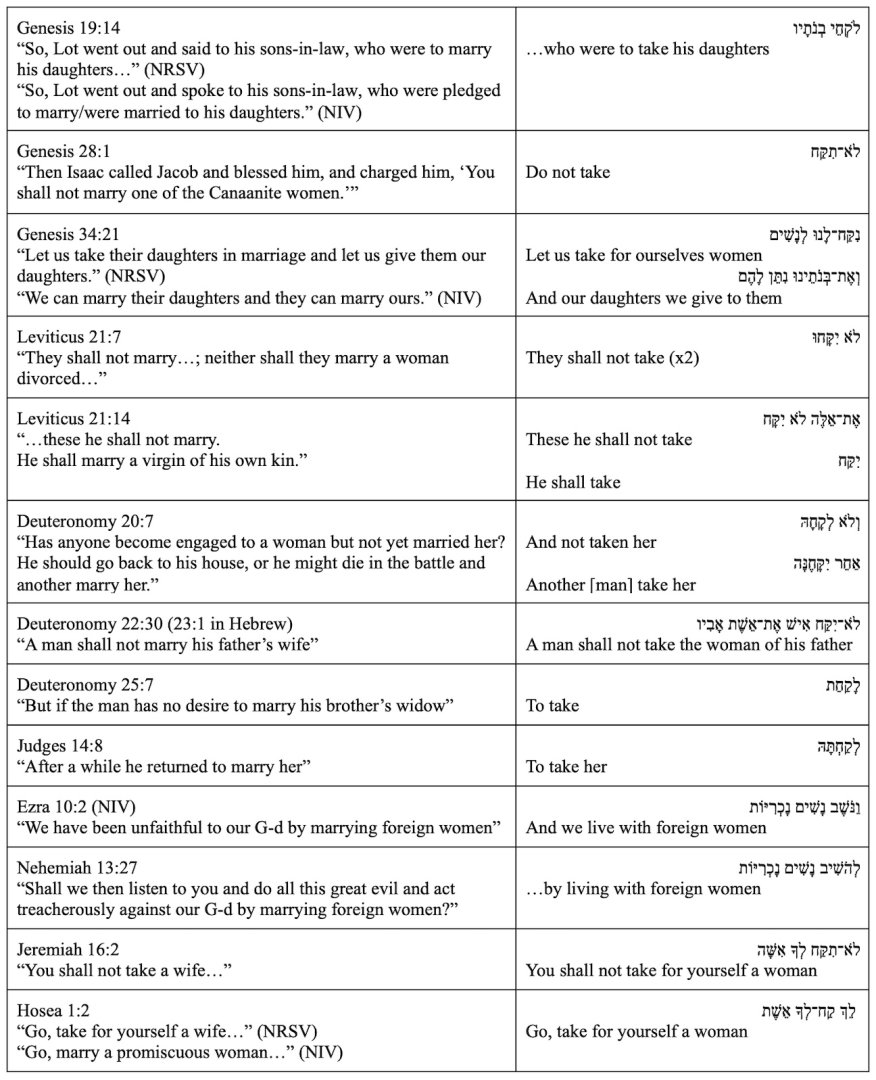

When the verb in the Hebrew, lqch, is used in relation to a man acquiring a wife, in our terms, you will see in the English some form of the verb “to marry.” The thing is, lqch simply means “to take.” It also turns out that lqch is the most common verb used (of the four mentioned above), so it is worth our time to sort this out a bit. The best way to see what is going on here is to see a list of passages that consistently use “marry” in the more than 50 English translations as compared to ones that translate the same verb, lqch, into English using “take.” Please take a few minutes to process the content in the two following charts. In both, in the left-hand column you will see the verse and one or two common English translations of it. In the right-hand column you will see the Hebrew (in case either you are familiar with it, or you would like to compare the forms) and a wooden translation of it. The main point here is to sit with how differently their language implies they were thinking of this relationship and the initiating of it than we tend to today.

Table 1: “Take” Translated as “Marry”

You might wonder if this “take” rendered as “marry” is all that big of a deal, since people often use this language during wedding ceremonies: “Do you take [enter name] to be your lawfully wedded husband/wife?” But it is an important issue, since in the ancient context, the taking was by the man, and was an exchange between the men involved. A man would take a woman from her father after paying the father for her in some way. If a woman happened to be depicted as going along with this exchange, you might want to keep in mind who wrote these stories and who benefitted from them. To be clear, in not a single instance is the woman given a voice or a choice in the matter.

But the distinction is perhaps made clearer when we see that the same verb in the Hebrew, when used in any other situation, is consistently translated as “take,” as the next table indicates.

Table 2: “Take” Translated as “Take”

There are three other verbs used in the Hebrew Bible that are consistently translated with marriage language, chtn, nsa, and yshb. That last one is the easiest to describe, as it suggests that a person is forced or compelled to live with another. A kind rendering of it might be a parallel to when a couple lives together for seven years in California (USA), for instance, they are then considered legally married. It is called a common law marriage. In the context of the Hebrew Bible, it is most common in Ezra and Nehemiah, referring to how men yshb-ed with women, caused women to live with them, when they had returned from exile in Babylonia.

The verb nsa is a bit unsettling in this context, I must warn you. Its primary definition is “to lift or take away by force or with strength or power” (BDB, 669). Even with the best of intentions behind this forced removal, it seems to me that it is quite different from the mutually entered into relationship that people usually think of marriage being today. Both of Elimelech and Naomi’s sons nsa women in Moab, and Solomon’s son King Rehoboam acquired women using the lqch and the nsa means.

Finally, there is the verb chtn and its noun cognates. This one is a bit tricky to explain, in part because in the biblical storyline it is not entirely clear what is happening. But what is certain is that the chtn is referenced when one party is from a people other than the Hebrews/Israelites, a people that did not practice circumcision. That is the concern, what did the penises of the people involved look like. The suitability of the match was focused on which god the people belonged to and worshiped. While this is often still a concern today, that people of two different religious traditions might struggle in a marriage together, there is no reason to suggest that this verb form and its noun cognates reflect a concern for mutual respect of the other’s choices. The Hebrew Bible is extensively caught up in the business of endorsing the worship of one particular god over all of the others in the region. This form of pairing up is a nod to this concern as well.

When we look at the four verbs involved in a pairing up situation in the Hebrew Bible, we have men taking women; we have a man forcefully removing a woman from her people to have her for himself; we have men forcing women to live with them; and we have a concern for perpetuating the worship of the god of the Hebrew Bible. None of these actions, it seems to me, is talking about two people choosing to pair up, based upon love, and/or being some form of mutually respected partners in the process. In other words, what these ancient stories tell us is that these ancient people were concerned about different things in these coupling scenarios than we tend to be today. Their language about it all speaks volumes. I think we should be clear about the gap between what they were interested in, or concerned about, and where our concerns lie today.

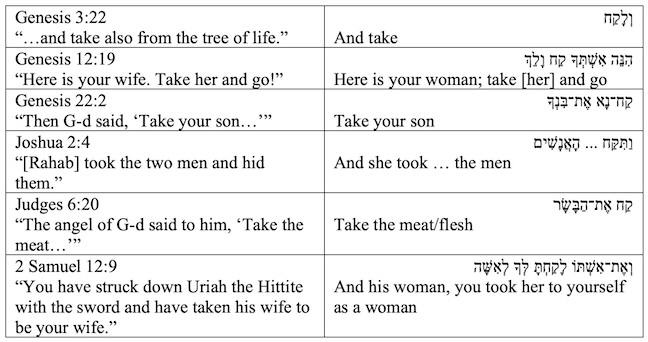

The same is true, then, for the way that men and women are talked about, in both primary testaments of the Christian Bible. We, today, have many ways to talk about people in terms of being in a couple or formally married; we have labels to indicate these distinctions. In contrast, what we see in biblical texts, in the original languages, is no indication that they wanted or needed to make such distinctions. A woman was a “woman” prior to being taken in by a man, and still called a “woman” thereafter. The same was true of a man prior to taking a woman and after. There was not, yet, terminology to indicate the change in status that we are accustomed to seeing and using today. All this tells us is that they were thinking of people and pairing up quite differently than we tend to today.

The most powerful example in the Hebrew Bible of why this matters (for most Christians) is contained in Genesis 2:24, “Therefore, a man will leave his father and mother and cling to his woman, and the two will be into one flesh.” Every English translation, but one, calls the woman “his wife”[2] instead of “his woman.” They all layer onto the text the idea that these two will “be married” before they come together and have some physical intimacy. Please consider all of the reasons that a translation committee might make such a leading translation choice. Please also consider how powerful it has been for millions of people to read and be informed by that choice.

What you will find in the next table is a comparison between language used today and language in biblical texts in terms of the labels ascribed to men and women, pre- and post-pairing. In the left-hand column you will see “pre-pairing” and “post-pairing.” The next column has some of the terms that people use to indicate those statuses today. Next are the terms in the Hebrew Bible used for men and women in the two groups, pre- and post-pairing up. In the final column you will see the terms used in the Greek of the Newer Testament for the same.

Table 3: Pre- and Post-Pairing Up

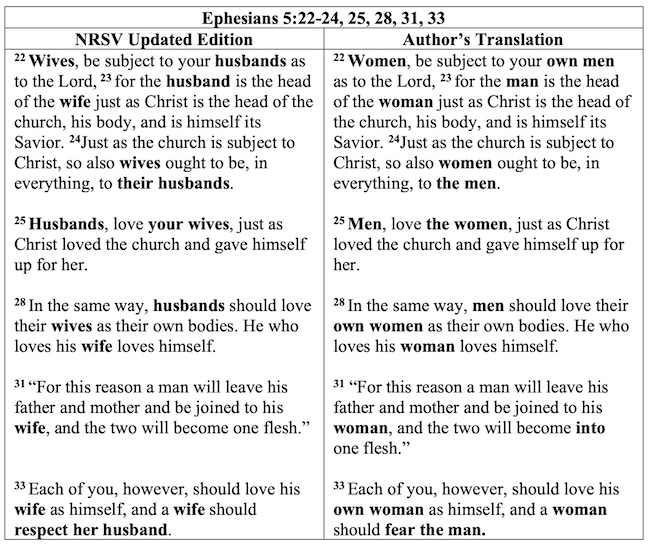

You are not alone if you prefer to see these distinctions being applied, if a table such as this one is a bit abstract. That is why you will see in the last table, in the left-hand column, a typical translation of selections from Ephesians 5 and, in the right-hand column, my own rendering of the same verses. Simply put, I am trying to highlight for you the impact it has on many of us when we change out the married language for the more raw original terminology. After taking a few minutes to process this next table, I wonder if you will consider that we could (or perhaps should) make the same change every time we see “husband” or “wife” terminology in both testaments of the Christian Bible: we could switch them out with “man” and “woman,” instead.

Table 4: Ephesians 5 Translation Comparison

These matters of terminology made a significant difference for me when I first encountered them and considered how often they happen in the Bible. It seems to me that when the translations smooth over the objectifying language or the action verbs that imply force and coercion are involved, we have been misled. As much as I wish to support loving couples choosing to marry today, I also wish to be clear about how differently these ancient people wrote and thought about the dynamic between paired-up people in their day. Please do mind the gap.

[1] It is important to note that we do only see hetero-presenting couples talked about as married in the Bible. Parts 1 and 3 of this series are aimed at helping people make a distinction between what the biblical texts endorse and what is “allowable” today, in terms of marriage.

[2] The one translation that does not use “wife” is a Jewish translation that simply transliterates the Hebrew letters instead of making a decision about how to render it.