By Katia Cytryn-Silverman

The Institute of Archaeology

and The Dept. of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Photos by David Silverman

Aerial by Yuval Nadel

April 2010

Tiberias is located on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, some 150 km north of Jerusalem via the Jordan Valley (or almost 200 km if travelling via the Sea Route), and approximately 160 km from Damascus. The city topography is best described by the Jerusalemite geographer of the tenth century, Muqaddasī:

“Ṭabariyya is the capital of Jordan and a city of Wādī (the Valley of) Kan‘ān. It is situated between the mountain and the lake, cramped, with suffocating heat in summer, and unhealthy.”

Tiberias, named after the emperor Tiberius, is believed to have been founded by Herod Antipas, son of Herod the Great, as his capital in 19 AD. During the second century, when the city was under direct Roman rule, the construction of a temple honoring Hadrian (a Hadrianeum was begun in the city center, never to be completed.

In the third century, Tiberias flourished: not only was it granted the status of a Roman colony, but it also became the capital of the Jewish people when the Sanhedrin and the Patriarchate moved there from Sepphoris. Here the Palestinian Talmud was compiled. During the sixth century, “Yeshivat Eretz Israel,” the supreme religious institution for the Jews in Palestine and the Diaspora, was established in Tiberias, where it continued to flourish well into the tenth century, when it moved to Jerusalem. Even then Tiberias continued to serve as a center and a home to the Massorites (who dealt with the correct vocalization of the Holy Scriptures), Hebrew grammarians, poets, and preachers.

From the fourth century onwards, Christian life gradually developed in Tiberias, though apparently with a difficult start. According to a passage in Epiphanius’ guide to pilgrimage dated to the last quarter of the seventh century, Count (Comes) Joseph from Tiberias, a Jew converted to Christianity and a protégée of Constantine (reigned 306-337) planned to build a church at the site of the unfinished Hadrianeum. Local Jews often disrupted his work; eventually he built a small church at the site of the temple, left the city and settled in Beth Shean. By the Late Byzantine period, nevertheless, Tiberias was clearly listed as a bishopric, and according to the Commemoratorium of the sixth century, it had five churches and one convent.

Ṭabariyya, as it is called in Arabic, was conquered by the Arab armies in 635. According to al-Balādhurī (d. ca. 892), the terms of surrender guaranteed a smooth and peaceful change of government:, the Arab conquerors taking possession only of those houses and houses of prayers in Tiberias which had been abandoned, and profiting from the taxation of goods. The commander Shura Rasana, to whom the city surrendered, also allotted the location where the mosque for the Muslims was to be erected.

Ṭabariyya was chosen as the capital of Jund al-Urdunn, ultimately to the detriment of Baysān/ Scythopolis. It is not clear, nevertheless, when exactly this shift of capitals took place.

Despite its historical significance and numerous excavations conducted since the 1930s, little was published until recently on the archaeology of Tiberias.

In the 1950s, salvage excavations by B. Ravani took place in the area to the south of modern Tiberias, where a sports center was to be built. A multi-phased bath-house, together with a portion of the city’s main south-north street-the cardo, and a pillared building (identified until recently as a covered market of the Byzantine period), were uncovered in the course of these excavations.

In the 1960s, further work took place along the lakeshore uncovering the remains of a sizeable basilical structure, whose erection was attributed to the Byzantine period (4th century) and was originally identified as a church, an identification no longer accepted. This basilica building drew the attention of Prof. Y. Hirschfeld of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who resumed excavations in this important site in the 1990s. His work was unfortunately cut short due to his passing away in 2006. Hirschfeld, together with K. Galor of Brown University, believed that in its main phase, this building was used as the seat of the post-70 “Sanhedrin.” According to this much disputed view, after the latter was dispersed in 358 by Roman emperor Theodosius, the building was adapted to serve administrative purposes of the government.

South of this site are the remains uncovered in 1973-1974 by Prof. G. Foerster of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His works defined the southern limits of the Byzantine city, and produced a clear stratigraphy, together with a good chronological sequence for the material finds – especially those from the Islamic layers, all carefully studied and eventually published in 2004 by D. Stacey.

The main feature exposed by Foerster was the city’s southern gate and the starting point of the cardo, going back to the Roman period. The walls attached to the towers were dated to the Byzantine period, while structures encroaching upon the Roman street were dated to the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. These remains have recently been re-exposed and are now part of the Berko Archaeological Park of Tiberias.

The changes which took place in the city of Tiberias from its inception until its Islamization in the seventh century are hinted at by the finds from the excavations mentioned above, as well as from the salvage excavations carried out in the past years by the Israel Antiquities Authority. Yet, apart from the Anchor Church on Mount Berenice, the remains of a sixth century synagogue, a fifth (?) century church and a small mosque (?), we are still far from knowing about the thirteen synagogues mentioned in the fourth century (Bavli, Berakhot 8a, 30b) and the five churches mentioned in the sixth century (Commemoratorium). Tiberias in 724, i.e., during the reign of Hishām b. ‘Abd al-Malik (r. 724-743), mentions that “There are a large number of churches and Jewish synagogues there.”

Likewise, little was known about Tiberias’ congregational mosque, mentioned by al-Muqaddasī:

“The mosque is large and fine, and stands in the marketplace; its floor is laid in pebbles, and the building rests on pillars of joined stone.”

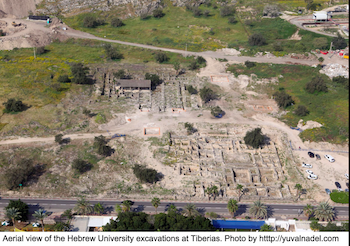

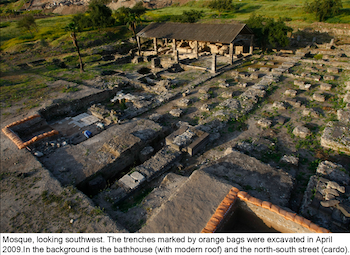

Since Spring 2009, the author, together with a staff of students of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, workers and volunteers from Israel and abroad, have been excavating the center of the ancient city. The project is investigating the partially excavated pillared building, previously identified as a Byzantine market, and now thought to be a congregational mosque.

Today, several sets of bases can be seen among the remains, relating to various stages of this building. The main set consists of basalt bases incorporating Jewish tomb doors dated to the Roman period (2nd-3rd centuries).

This layout of the mosque is comparable to that of the Great Mosque of Damascus, the capital of the Umayyads, to which the pillared building in Tiberias seems to be connected by both common proportions and similar decorative programs.

The findings from our excavations allow the reconstruction of the heart of the Islamicized city, which sometime after its conquest by the Arabs in 635 became the provincial capital of Jund al-Urdunn.

The 2009 excavations confirmed the reinterpretation of the “covered market” as an Early Islamic mosque: the mosque's prayer niche was identified, as were its south-eastern corner, and the western and the northern walls enclosing its courtyard. A series of floors are testimony to the building’s continuous use from the eighth through the eleventh centuries, while a collapse of roof-tiles teaches us of the building's demise.

Part of a geometric mosaic was uncovered under the remains of the mosque’s south-eastern corner. The study of this mosaic, composed of large tesserae, reminiscent of late Byzantine-Early Islamic examples, will shed light on the unsettled chronology of some comparable church mosaics in the region.

During the coming seasons (April 25-May 14, 2010 and October 3-29, 2010), our project aims to better our understanding of the relationship between the mosque and its surroundings. Due to the centrality of the mosque within its urban context, we plan to determine its connection to elements which were partially exposed in previous excavations, such as: the cardo, the basilical structure, an ‘Abbāsid street, a possible administrative complex and a Byzantine church.

To learn more about this exciting project, as well as options for volunteering, please visit:

http://archaeology.huji.ac.il/Tiberias

or contact:

tiberiasexcavation@yahoo.com