The Deuteronomic History and the Book of Chronicles are contemporary historiographies that were produced by different scribal guilds (one in Babylon and one in Jerusalem) that nevertheless have a common institutional ancestor in the Deuteronomic school of the Babylonian exile. The split occurred when the Deuteronomic school returned to Jerusalem with Zerubbabel to provide scribal support for the rebuilding of the temple and its cult, leaving what became the Chronistic school in Babylon. These two schools continued to interpret their once common source in ways that is quite similar to how oral traditions develop allowing multiformity, thereby producing the two contemporary historiographies. Then the two schools with their different historiographies came into contact later when Ezra and other Chronistic scribes returned to Jerusalem.

By Raymond F. Person, Jr.

Ohio Northern University

Professor of Religion; Chair

Department of Religion & Philosophy

September 2011

The consensus models that have informed biblical studies for many years have been under assault for the past twenty years or so. For example, Martin Noth’s understanding of the Deuteronomistic History (Deuteronomy–2 Kings) has been challenged from various angles, including dating the final Deuteronomistic redaction later. The breakdown in the consensus model has been significantly influenced by various methodological approaches, including text criticism’s insistence of textual plurality as the norm in the ancient world and the study of oral traditions and literature with its roots in oral traditions. In The Deuteronomic History and the Book of Chronicles: Scribal Works in an Oral World,1 I build upon my earlier work dating the Deuteronomic History to the Persian period, taking seriously these two methodological approaches.

The consensus model has stated that the relationship between the Deuteronomistic History and the Book of Chronicles is sequential, with the Deuteronomistic History preserving preexilic and exilic materials using Standard Biblical Hebrew as the primary source for the later Book of Chronicles, which is a major postexilic revision of Samuel–Kings and other sources in the language of Late Biblical Hebrew. Thus, any place that the Book of Chronicles lacks material found in Samuel–Kings must be a deliberate omission of the earlier material and any place that the wording in parallel passages differs must be deliberate substitutions of the earlier material, all of which betray the distinctive theology of the Chronicler.

I directly challenge this consensus, concluding rather that the Deuteronomic History and the Book of Chronicles are contemporary historiographies that were produced by different scribal guilds (one in Babylon and one in Jerusalem) that nevertheless have a common institutional ancestor in the Deuteronomic school of the Babylonian exile. The split occurred when the Deuteronomic school returned to Jerusalem with Zerubbabel to provide scribal support for the rebuilding of the temple and its cult, leaving what became the Chronistic school in Babylon. These two schools continued to interpret their once common source in ways that is quite similar to how oral traditions develop allowing multiformity, thereby producing the two contemporary historiographies. Then the two schools with their different historiographies came into contact later when Ezra and other Chronistic scribes returned to Jerusalem.

Although from our modern perspective, the Deuteronomic History and the Book of Chronicles differs significantly, this would not necessarily be the case from the perspective of the ancient Israelites. From the comparative study of living oral traditions and texts in primarily oral societies, we can see how traditions can allow for what from our modern highly literate perspective appears to be significant theological and historical variations, while nevertheless valuing the tradition in all of its multiformity so that what appears to us to be contradictory can be understood from their perspective as complementary. In that sense, the broader tradition cannot be represented by any one text but requires the collective voice of all of the texts to represent the fullness of the same tradition. Thus, any one text must be understood as an imperfect instantiation of the broader tradition.

When we take seriously this perspective gained from the comparative study of oral traditions, we can see more clearly the multiformity within each of these historiographies as well as in their relationship. Within the Deuteronomic History, such multiformity is quite obvious in the textual plurality of Samuel–Kings—that is, the textual variants among the Masoretic Text, the Septuagint, and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Within the Book of Chronicles, such multiformity is found in the tensions between the genealogies in 1 Chronicles 1-9. Since each of these historiographies contain such multiformity within them, I explored the possibility that the purported differences between Samuel–Kings and Chronicles do not necessarily represent theological conflicts between the Deuteronomic school and the Chronistic school, but simply represent how the same broader tradition developed independently in these two scribal schools, leading to two historiographies, both of which are faithful representations of the same theological tradition.

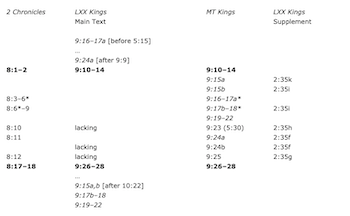

In The Deuteronomic History and the Book of Chronicles, I devote an entire chapter to the discussion of multiformity in oral traditions and within both the Deuteronomic History and the Book of Chronicles. I then devote a chapter each to applying this perspective to the synoptic material and the non-synoptic material. Here I provide only one example of this approach from the synoptic material, specifically 1 Kings 9:10–28//2 Chronicles 8:1–18. For my analysis of this material, I drew significantly from the work of the text critic, Julio Trebolle.2 Trebolle noted how text critical analysis of the Kings passage in combination with the Chronicles passage illuminates the textual history of this material. His analysis can be summarized in the following table:3

What Trebolle called the “triple textual tradition”—that is, Chronicles, MT-Kings, and LXX-Kings agreeing in content and order—is bolded. Those verses that are found in both LXX-Kings and MT-Kings but in different orders are italicized.

Trebolle insisted that the textual plurality evident within the textual traditions of Samuel–Kings as well as between Samuel–Kings and Chronicles points to the ancients’ acceptance of such multiformity. However, it might be helpful to look at this material assuming a unilinear textual history, since it is possible that these various texts are expansions of a shorter common written source. If this is the case, then the common source concerning Solomon’s interactions with Hiram contained 2 Chr 8:1–2, 17–18//1 Kgs 9:10–14, 26–28 (the material agreeing in content and order). The expansion in LXX-Kings occurred either before or after the common source (given in order of occurrence: 9:16–17a, 24a, 15, 17b–18, 19–22) or in the Supplement (2:35). The expansion in MT-Kings and MT-Chronicles occurred within the common source (2 Chr 8:3–12; MT-1 Kgs 9:15–25).

However, from the perspective of the important role of multiformity in primarily oral societies, the assumption that each text developed in some unilinear direction may be too simplistic. That is, if any one text is considered to be an imperfect instantiation of the broader tradition, such an early common source (possibly 2 Chr 8:1–2, 17–18//1 Kgs 9:10–14, 26–28) was not considered to preserve the tradition in its fullness. Therefore, although in one sense additions were made to later texts, these additions may nevertheless have been present within the broader tradition as preserved in the collective memory of the community and, therefore, in a real sense are not additions at all. Rather the textual representation of the broader tradition expanded in order to record in writing what had already existed in the tradition. Since the tradition valued multiformity, different texts could faithfully represent the tradition, even though the textual additions occurred in different locations. The different locations of these textual additions simply mirrored how the narrated events are not necessarily fixed in a particular linear order in the broader tradition as preserved in the collective memory. If this is the case, then each of the extant texts of 1 Kings 9:10–28//2 Chronicles 8:1–18 can be understood as faithfully representing the broader tradition although imperfectly. Furthermore, the tradition in its fullness is best represented by understanding the collective tradition as found in all of the extant texts, although this too would be imperfect, since not all ancient texts have been preserved and we do not have access to whatever was in the collective memory but was never written down.

Trebolle’s chart provides a helpful summary at the macro-level of analysis for these texts. However, the chart might create a false impression that would minimize the multiformity between Kings and Chronicles. Therefore, I want to address this possible misreading by briefly analyzing one passage in the “triple textual tradition,” 1 Kgs 9:10–14//2 Chr 8:1–2.

MT-1 Kings 9:10–14MT-2 Chronicles 8:1–2

10At the end of twenty years when Solomon built the two houses, the house of the Lord and the house of the king, 11Hiram, king of Tyre, supplied Solomon with wood of cedar and cypress and with gold, all that he desired. Then King Solomon gave to Hiram twenty cities in the land of the Galilee. 12But when Hiram came from Tyre to see the cities that Solomon had given him, they did not please him. 13He said, “What are these cities that you have given to me, my brother?” He called them, “the land of Cabul,” as it is until this day. 14But Hiram had sent to the king a hundred and twenty talents of gold.1At the end of twenty years when Solomon built the house of the Lord and his house, 2Solomon rebuilt the cities that Huram had given to Solomon and he settled there the sons of Israel.

Both texts describe Solomon’s building projects and mention Solomon’s building of the temple and the palace. They include references to Hiram/Huram who provided material and workers for both projects (see 2 Chr 2:3–18). Both contain references to the twenty cities that changed hands between Solomon and Hiram/Huram with some possible variation. Kings explicitly notes that Solomon gave the twenty cities to Hiram as a gift but that Hiram possibly returned them to Solomon as unworthy cities; Chronicles could be assuming knowledge of the same tradition, but that is not clear. Thus, the multiformity that we see at the macro-level also occurs at the micro-level—that is, these texts display variety in the order of the narrated events and in their wording of even the common material. However, this variety does not necessarily require theological conflict or even different historical reconstructions from the perspective of the ancients. Where we see conflict the ancients may not have.

Hopefully, this one example illustrates well why I am convinced that too often modern biblical scholars are quick to postulate theological and historical conflict on the basis of what from our modern, highly literate perspective appears to be significant differences, but from the perspective of ancient Israelites who lived in a primarily oral society may be understood as inconsequential variations that simply represent the multiformity and breadth of the broader tradition as preserved in texts and more importantly in the collective memory.

Notes

1 Raymond F. Person, Jr. The Deuteronomic History and the Book of Chronicles: Scribal Works in an Oral World (Ancient Israel and Its Literature, 6; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2010).

2 Julio Trebolle, “Kings (MT/LXX) and Chronicles: The Double and Triple Textual Tradition,” in Reflection and Refraction: Studies in Biblical Historiography in Honour of A. Graeme Auld (eds. Robert Rezetko, Timothy H. Lim, and W. Brian Aucker; Leiden: Brill, 2007), pp. 483-501.

3 Trebolle, “Kings (MT/LXX) and Chronicles,” 495.