See Also: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Caesarea Maritima. Caput Judaeae, Metropolis Palaestinae (Brill, 2011)

By Joseph Patrich

Institute of Archaeology

Hebrew University of Jerusalem

October 2011

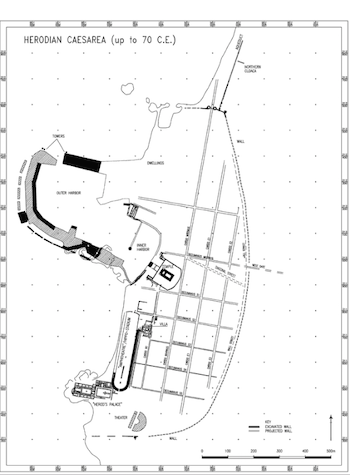

features: the diagonal street, suggested by

Jewish Antiquities 15.349, and the peripheral

“wall street,” suggested by the Rabbinic sources,

Mishnah Oholot 18:9 and Tosefta Ahilot 18:13)

(Drawing: A. Iamim).

Caesarea Maritima was founded by Herod in 22-10/9 BC on the site of a deserted Hellenistic coastal town called Straon’s Tower. According to Josephus Flavius (Jewish War 1.408-15; Jewish Antiquities 15.331-41), Herod established an elaborate harbor there. It was called Sebastos, a city with streets laid in a grid pattern. The city, like the harbor, were named after the emperor Caesar Augustus, Herod’s patron in Rome. In the city, Herod erected a temple which he dedicated to Rome and Augustus, a theater, and an amphitheater, as well as a royal palace - basileia. All the Herodian structures were built of local kurkar stone coated by a layer of polished white stucco, the “white stone” praised by Josephus. Marble was first imported after 70 CE under the Roman regime.

Caesarea served as the main harbor and capital city of Herod’s kingdom and of the later Roman province of Judaea / Syria Palaestina, the seat of the Roman governors and financial procurators of the province. Vespasian made Caesarea a Roman colony in 71 or 72 CE, and Alexander Severus (222-235 CE) raised it to the rank of metropolis. In the Byzantine period, it was the capital of Palaestina Prima and a Metropolitan See, subordinate to the Patriarch of Jerusalem since the mid-5th century. In the second and third centuries, it was the hometown of a Jewish academy headed by Rabbi Oshaiah and Rabbi Abbahu and of a Christian academy headed by Origen and Eusebius; it was the town of origin of Procopius, the notable historian in the court of the emperor Justinian in the 6th c. The Arab conquest in 640 brought a sharp decline of urban life that might have started already following the Persian conquest of 614. Islamic and Crusader Qaisariyah was a small town of marginal importance, located around its decaying harbor.

In recent years (1992-2002), excavations have tremendously augmented previous archaeological information on the site, mainly on the temple platform and the southwestern zone. Our information on the northern and eastern sectors of the city is more meager. Underwater work also augmented previous knowledge of the harbor and its gradual demise.

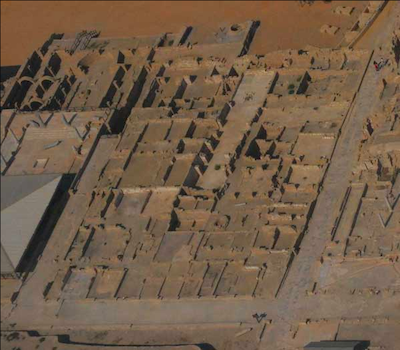

The Harbor was a huge enterprise, compared by Josephus to Piraeus, with many quays and anchorage spots. It was constructed of huge stones, including materials imported from Italy, using Roman technology. The outer mole and breakwater, on the south and west, penetrated ca. 400m into the sea, enclosing the outer and intermediate basins; the inner basin was rock cut into the land incorporating the enclosed harbor (limen kleistos) of the Hellenistic Straton’s Tower. The entrance, flanked by three colossal statues on either side, was from north, at the west end of the north mole. Several inscribed lead ingots found in 1993 over the northwestern end of the mole suggest that this section of the pier was submerged already at the end of the first century CE due to tectonic slumping. The harbor underwent a large scale of reconstruction by the emperor Anastasius (491-518 CE), but by that time, the inner harbor was already silted, giving new ground for the construction under Arab dominion of a new neighborhood of dwellings.

12/12/1944 (Survey of Israel – MAPI).

Walls and Gates: Two semi-circular city walls are still recognizable in aerial photographs beyond the rectilinear shorter line of the Arab-Crusader wall. The inner line is Herodian and the outer is Byzantine. The Herodian wall had a northern gate flanked by two circular towers. The southern end of this line was exposed in the recent excavations to the south of the theater, with a circular tower attached to its external face. The Byzantine wall encompassed a semi-oval area of 1500x830m - two to three times larger than before. The road system that had emerged from the city suggests the probable location of the gates. The northern Byzantine gate was destroyed by the sea; the southern gate, originally embedded in the scaenefrons of a theater, was uncovered blocked by marble statuary to protect against the final attack of the Muslim army in 640. A Greek inscription mentioning a bourgos was uncovered near the conjectural location of the eastern gate. A monumental arch referring to Caesarea as a metropolis was located nearby.

In the 6th or 7th century, an inner fortress (kastron) with semi-circular towers was constructed around the theater that already went out of use.

The Street System and Urban Plan: Archaeology confirmed Josephus’ account that Herod laid down a well-planned grid of streets with a sophisticated sewage system underneath. The recent excavations in the southwestern zone uncovered at least four successive street levels, sticking to the same urban plan. The insulae of the grid system were 65 x 95 m in dimension; those in the northern zone might have been longer. The orientation of the temple platform overlooking the harbor was slightly offset to this grid pattern.

Temples: Of the many temples suggested by the city coinage, inscriptions, and statuary, only three temples yielded architectural remains. On top of the temple platform, dominating both city and harbor, the foundations and scattered architectural members of Herod’s temple to Roma and Augustus were found. The podium was constructed on top of a U-shaped elevated platform, leaving an open esplanade below, to the west, in a lower terrace, along the eastern mole of the inner harbor. The Imperial cult is also attested by two inscriptions, one mentioning a Tiberieum and the second a Hadrianeum.

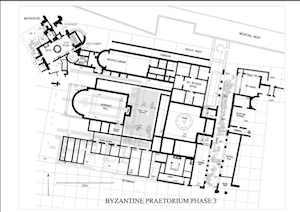

In the southwestern zone, a Mithraeum was installed in the third century in one of the vaults underneath the audience hall in the praetorium of the financial procurator. The shrine of the western hippodrome/amphitheater was dedicated to Kore. The cult of the local Tyche, identified as Isis Euploia since the days of Hellenistic Strato’s Tower, was still celebrated in the first half of the 4th c. CE. This deity, depicted in monumental statuary as well as on small objects such as figurines and gems, was conceived as the genius of the Roman colony. Her annual feast was March 5th – the date of Navigium Isidis – the beginning of the sailing season in the Mediterranean after the winter storms.

Phase 3 (Drawing: A. Iamim)

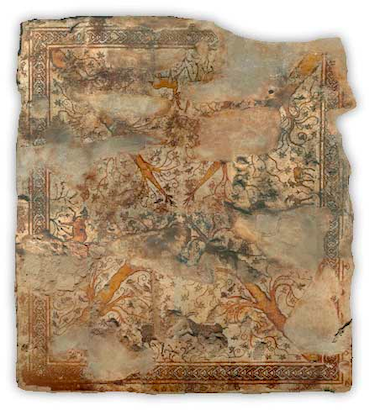

Palaces and Praetoria: Herod’s palace, constructed on a promontory to the south of the harbor, was enlarged and elaborated, becoming the praetorium of the Roman governors. In 77/78 CE, a second praetorium was constructed by the emperors Vespasian and Titus in the first urban insula to the south of the harbor for the use of the financial procurators of the province that was elevated in rank and governed by a legatus augusti pro praetore of a senatorial rank. This palace later became the residency and officium of the Byzantine governor. The two praetoria had vast courtyards and gardens and elaborate bathhouses. Two other palatial mansions were constructed in the Byzantine period in the southwestern zone between these two praetoria. The northern one, exposed in its entirety, had an elaborate bathhouse in a good state of preservation. It was constructed in the fourth century over a Roman first-century “villa” that extended over a vaster area. The second, constructed in the sixth century, had a two-story peristyle courtyard with a triconch triclinium. In a lower terrace, on the west, a garden and a fountain were installed, leading to a private beach. A unique opus sectile workshop with magnificent designs was uncovered in one of the side rooms of this Byzantine palace.

Dwellings of a more regular type, yet quite spacious, were uncovered in several locations, mainly in the northwestern zone.

Sports Arenas: Herod’s theater is located at the southern end of the city, to the east of his palace. Herod’s amphitheater, uncovered in the recent excavation along the sea, between the palace and the harbor, turned out to be a hippo-stadium, appropriate for athletics as well as for chariot races (see fig 1-fig 2). The arrangement of the starting gates - five on either side of a central wide gate and lanes that run parallel to the longitudinal axis of the arena, indicate that the races established by Herod followed the Olympian tradition of chariot racing, rather than that of the Roman circus, with its factions. Later transformations in the arrangement of the starting gates, with lanes arranged radially, had adhered to the Roman style. At the final phase - perhaps early in the third century - the arena was truncated, and the hippo-stadium was converted to an amphitheater. This was deserted later in that century due to erosion by the sea waves.

Later in the Roman period, presumably in the second or third century, a “canonical,” oval, Roman amphitheater (recently excavated) and a Roman circus, constructed under the emperor Hadrian (117-138 CE), were installed in the northeastern and southeastern zones respectively. The Roman circus, with an obélisque decorating its spina, continued to be in use to Byzantine times. According to Malalas, Vespasian converted a Jewish synagogue into a vast odeum. Its location is so far unknown.

Other monuments and buildings are mentioned in the literary sources - both Greco-Roman and Rabbinic - and in the inscriptions: a tetrapylon, porticoes, stoas, and colonnaded streets (platea), a dome-like structure overlaying a public thoroughfare, and market places. A sigma-shaped market building of Roman and Byzantine date was exposed in recent excavations on the southern side of the temple platform.

Nymphaea Bath Houses and Latrines: An elaborate nymphaeum, with three niches holding statues, adorned the northwestern projections of the temple platform. A network of lead and terra cotta pipes led water to the street and private fountains, and latrines were dispersed throughout the city, like the one found in the cardo-dcumanus intersection in the southwestern zone. According to Malalas, Antoninus Pius erected a public bath at Caesarea. The “baths of Cornelius” – where the first Gentile was baptized by the apostle Peter, are mentioned in a 4th-century Christian itinerary. All bathhouses uncovered so far in Caesarea are associated with palaces and villas; they are not the huge thermae of the Roman imperial style.

Izdarechet)

Warehouses and Horrea: As a maritime city and provincial capital, the city was provided with plenty of warehouses and horrea for both import-export trade and for stocking food staffs in adequate quantities to prevent inflation of prices. Warehouses of several types were uncovered in the southwestern zone and around the harbor, mostly dated to the late Roman and early Byzantine periods. These are long vaulted horrea and “courtyard” and “corridor” warehouses. Particular features of these warehouses are vast halls with crude mosaic floors that held vast dolia and under ground granaries revetted by walls of well-drafted blocks imbedded in a thick layer of oily lime mortar.

Of the various synagogues that existed in Caesarea, only one was exposed in the northern part of the city, the site of Strato’s Tower. Another Jewish synagogue was converted by Vespasian to an odeum.

Several Christian Buildings associated with New Testament events and with the persecutions of martyrs are mentioned in the Byzantine itineraria: the houses of Cornelius and Philip, the chamber of the four virgin prophetesses - Philip’s daughters, the burial place of the martyrs Pamphilus and Procopius, and the latter’s chapel. More chapels and churches are known from literary sources. However, only two churches have so far been exposed. By ca. 500 CE, an octagonal church, decorated and revetted in marble, had replaced Herod’s temple of Roma and Augustus on the temple platform. Access from the west was by means of a monumental staircase raised over a broad vault. The western end of this staircase was founded on a platform of huge stones laid inside the inner harbor, adjoining the edge of the Herodian mole. The staircase was flanked on either side by six elongated vaults erected over the lower Herodian esplanade. A second, simpler staircase had an approach from the south.

An apsidal structure exposed to the south of the deserted Herodian hippo-stadium, overlaying the northeastern part of the Roman praetorium, interpreted as a Christian basilica, was rather a Samaritan synagogue. A martyrs’ chapel was installed in the pagan shrine (sacellum) of the truncated hippo-stadium where Christian martyrs were allowed to pray to wild beasts.

The Water Supply System: The Roman city got its water supply from the north by means of two aqueducts. The high level aqueduct reached the city as a double arcade carrying two channels. The later, western one is dated by inscriptions to the reign of Hadrian. The lower level aqueduct is a masonry tunnel, ca. 1.20m wide and 2.00m high, that got its water from an artificial lake constructed at the late 3rd century near the outlet of Nahal Tanninim to the Mediterranean. A Byzantine terra cotta pipeline reached the city from the north. A network of lead and terra cotta pipes running under the paved streets led the water to various public amenities: fountains, nymphaea, bath houses, latrines, and gardens. The palaces and rich mansions benefited from a running water supply as well. By the late Byzantine period, the water supply system deteriorated, and wells replaced the pipelines to some parts of the city.

The extra mural territory was densely settled and cultivated. Dwellings and suburban villas with mosaic floors were encountered in several locations.

The necropolis extended on all three sides around the city wall, but mainly to the east, as is attested by burial caves, burial inscriptions, and sarcophagi. A new Roman cemetery in which cremation in amphorae was the practice was uncovered in the recent excavations next to the southern end of the Herodian city wall on the outside.

Selected Bibliography

L.I. Levine, “Roman Caesarea: An Archaeological-Topographical Study” [Qedem 2] (Jerusalem 1975).

L.I. Levine, Caesarea Under Roman Rule (Leiden: Brill 1975).

L. Vann (ed.), “Caesarea Papers. Strato’s Tower, Herod’s Harbor, and Roman and Byzantine Caesarea” [Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series number Five], (Ann Arbor, MI 1992).

A. Raban and K. G. Holum (eds.), Caesarea Maritima. A Retrospective after Two Millennia. (Brill: Leiden-New York-Köln 1996).

K.G. Holum, A. Raban, J. Patrich (eds.), “Caesare Papers II” [Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series ] 1998).

Kenneth G. Holum, Jeniffer A. Stabler, and Edward Reinhardt (eds.), Caesarea Reports and Studies (Oxford: BAR Int. Ser. 1784, 2008).

A. Raban, The Harbour of Sebastos (Caesarea Maritima) in its Roman Mediterranean Context (Oxford: BAR Int. Ser. 1930, 2009).

J. Patrich, Studies in the Archaeology and History of Caesarea Maritima: Caput Judaeae, Metropolis Palaestinae. (Brill: Leiden-New York-Köln 2011).