With few scientific arguments to buttress their position, they [minimalists] proposed an imaginary, alternative history of biblical Israel and Judah. Instead of fostering a discussion between two competing paradigms based on the interpretation of data, the minimalists resorted to rhetoric and demagoguery, ignoring both the relevant archaeological data and the Bible.

See Also:

A Reply to R. Arav’s Review of Khirbet Qeiyafa Vol. 1

A Brief Note for Yosi Garfinkel

“The End of Biblical Minimalism?”

Essays on Minimalism from Bible and Interpretation

By Yosef Garfinkel

Institute of Archaeology

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

July 2012

I. Introduction

Conventional scientific procedure follows a logical pattern. In order to test a scientific hypothesis first one gathers the data, then analyzes it, and finally arrives at conclusions. It is legitimate to propose a new working hypothesis, to test it against the data, and if all known facts support the hypothesis, to propose a new interpretation. Such a new interpretation is commonly called a “synthesis” or “paradigm.” The accumulation of new data is the fuel that keeps science going. New data challenge old interpretations and create a necessity for new understandings. Sometimes different interpretations may be suggested, and different paradigms may exist side by side for a rather long period. New data may shed light on such debates and discredit competitive paradigms.

This is how biblical archaeology developed from the beginning of systematic excavations in Israel. Today, however, in some circles the paradigm has become more important than the data: when new data clearly show that an old paradigm is wrong, the scholars who created the flawed paradigm sometimes reject the new data and desperately attempt to keep the old paradigm alive. Articles reflecting such thinking are symptomatic of “paradigm-collapse trauma” and consist of groundless arguments, masquerading as scientific writing through footnotes, references and publication in professional journals. These articles recall a defense attorney quibbling over minutiae in an attempt to distract the jury from the main accusations against his client. Thus, not only were these scholars wrong to begin with, but they persist in reiterating the same error.

II. Biblical Minimalism and Pseudo Biblical Minimalism

There have been many competitive paradigms in the field of biblical archaeology over the years, but in the 1980s radically different ideas began to emerge. At first, the overemphasized connection with biblical tradition was criticized, and it was proposed to change the discipline’s name: from biblical archaeology to Syro-Palestinian archaeology. The name of the journal Biblical Archaeologist, published by the American Schools of Oriental Research, was changed to Near Eastern Archaeology. A further development was the rise of the so-called biblical minimalists, a movement that developed under the influence of post-modernism, embodying the hermeneutics of suspicion and deconstructionism. This movement questions the historicity of the biblical narrative largely by challenge the legitimacy of the Bible’s portrayal of the historical development of the Davidic dynasty. Particularly relevant to our discussion is the biblical narrative relating to the 10th century BCE, the period known as the United Monarchy. The so-called minimalist school claims that since the Hebrew Bible was written hundreds of years after the time of David and Solomon, the description of that era must be regarded as a literary composition unrelated to authentic historical facts.

Since the archaeological record was inconclusive, the minimalists assumed that the biblical account of the rise of the Davidic dynasty was a myth. The minimalists violated the conventional scientific procedure of moving in a logical progression from the data, to analysis and then to conclusions. Although the marginalization of large portions of the biblical narrative was not supported by the data, minimalist scholarship was unimpeded. With few scientific arguments to buttress their position, they proposed an imaginary, alternative history of biblical Israel and Judah. Instead of fostering a discussion between two competing paradigms based on the interpretation of data, the minimalists resorted to rhetoric and demagoguery, ignoring both the relevant archaeological data and the Bible. As an example, minimalists proposed that the Siloam Tunnel and its inscription be dated to the Hellenistic period, thereby repeating precisely what they accused the biblical writers of doing: creating a purely imaginary mythological/literary history.

This situation changed radically in 1993 and 1994, when several fragments of an Aramaic stele dated to the 9th century BCE were found at Tel Dan. This text specifically mentions a king of Israel and a king of the “House of David.” Reference to the House of David has subsequently been identified in the Mesha Stele, also dated to the 9th century BCE. Thus, there is at least one, possibly two clear references to David only 100–120 years after his reign. This is substantial evidence that David was both a historical figure and the founder of a dynasty, contrary to the minimalists’ claims.

The collapse of the minimalist paradigm is not surprising, since from the beginning it was based more on sensationalism than on sound methodology. The panicked reaction of the minimalists led to ideas that now appear preposterous, as reflected in the following article titles: “House of David Built on Sand,” “Did Biran Kill King David?” or “Eponymic Referent to Yahweh as Godfather.” But even worse, it was claimed that the Dan inscription was nothing but a forgery. The old paradigm had become more important than the new data. From my perspective, this was the point where, in certain circles, biblical archaeology was manipulated and turned into brutal biblical archaeology. By this I refer to a situation in which archaeology and biblical studies cease to be concerned with the past and instead, have been contorted to manipulate current academic politics or as a vendetta to defend injured egos.

The Tel Dan stele ended the first phase of the debate regarding the historicity of the Hebrew Bible. It showed that the mythological/literary paradigm was flawed. To dismiss the historical account of the Davidic monarchy as pure myth was untenable and nothing but unfounded post-modern ideology criticism (for a detailed discussion, with references, see Garfinkel and Ganor 2009:3–18; Garfinkel 2011a). The attacks by Prof. Davis on my recent article in Biblical Archaeology Review are a faint echo of the golden era of the minimalists, before the Tel Dan stele was found.

After the collapse of the mythological paradigm, the minimalists developed a new strategy: the low chronology paradigm. This approach attempted to lower the dating of the transition between Iron Age I and Iron Age II. This transition was traditionally dated to c. 1000 BCE (according to what is commonly referred to as high chronology). The new proposal dated this transition to c. 925 BCE (and is commonly referred to as low chronology). What was achieved by this? The Iron Age I in Judah and Israel was a period of agrarian communities organized along tribal lines. The subsequent period, the Iron Age II, is characterized by an urban society structured around a centralized state. Low chronology places urbanization only at the end of the 10th century BCE, effectively negating the possibility that David and Solomon were rulers of an organized kingdom, and making them mere local tribal leaders (Finkelstein 1996). In addition, low chronology argues that urbanism began in the northern kingdom of Israel while Judah only became a state toward the end of the 8th century BCE.

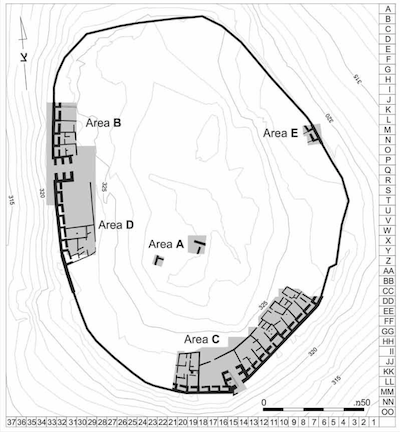

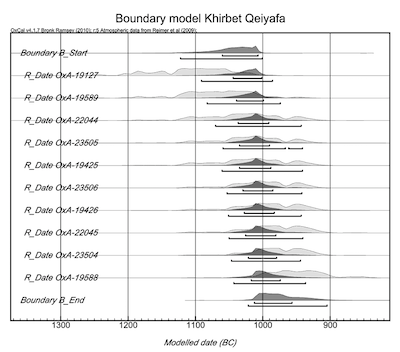

Our current excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa have far-reaching implications for the heated debate on the transition from Iron Age I to Iron Age II. To date we have excavated approximately 20% of the city and have uncovered a heavily fortified city with a casemate city wall, two gates, two gate plazas, 10 houses and three cultic shrines (Figs. 1–2). The dating of the city is based upon 10 olive pits tested at the Oxford University laboratories, and indicates that the city existed between 1020 to 980 BCE (Garfinkel and Ganor 2009; Garfinkel, Ganor and Hasel 2010, 2011, 2012). These new data entirely contradict arguments favoring the low chronology, which puts urbanization in Judah over 300 years later (Fig. 3).

Since publishing the results of our excavations, eight different articles have been published by Tel Aviv University scholars, challenging our data and attacking our interpretations: Na'aman (4 articles), Finkelstein and Piasetzky (1 article), Finkelstein and Fantalkin (1 article), Singer-Avitz (1 article), Dagan (1 article). All these articles focus specifically on Khirbet Qeiyafa. In addition to these, another article dealing with the Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon was published in the journal Tel Aviv (Rollston 2011), which is an organ of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University and edited by Israel Finkelstein.

I have no problem with scholars who suggest alternate interpretations of data from this or any other site. This is a healthy process in every scientific discipline. The fact that the Khirbet Qeiyafa excavations are the concern of so many scholars is a sign of the site’s importance. To the best of my recollection, never before has such a site, one of the smallest biblical cities in Israel, ever received so much attention. So scholars, please keep on writing: the more the merrier!

The Khirbet Qeiyafa excavations have invalidated the low chronology. Because there is no data to support the outdated low chronology paradigm of 1996, Finkelstein has attempted to overcome the fresh data in a variety of ways. A close look at each of the publications that criticize our interpretation or data reveals serious methodological flaws:

1. Following the second season of excavations Dagan (2009) argued that the entire Iron Age city dates to the Hellenistic period. This idea was based on pottery sherds collected during a surface survey that he carried out at the site nearly 20 years earlier. Archaeological strata and buildings buried deep in a site should clearly not be dated on the basis of surface sherds (Garfinkel and Ganor 2010).

2. Singer-Avitz (2010) argued that the pottery uncovered in the fortified city of Khirbet Qeiyafa should be classified as late Iron Age I rather than early Iron Age II. She presents three typological criteria as the basis for her analysis of the pottery. Later in that article she contradicts her own three criteria (Garfinkel and Kang 2011).

3. Finkelstein and Piasetzky (2010) dealt with the four radiometric dates from Khirbet Qeiyafa available at the time of their writing. They took the highest date and the lowest date and dated the city between these: 1050 to 925 BCE, thus ignoring accepted procedure, which calls for age determinations based upon a number of dates rather than single ones (Garfinkel and Kang 2011).

4. Finkelstein and Fantalkin (2012) recently claimed that we do not understand what is going on at Khirbet Qeiyafa at all, criticizing methodological shortcomings in both our field work and our interpretation of the finds. This article is divided into two sections. The introduction is a vicious attack on every possible aspect of the excavations. The second half suggests that Khirbet Qeiyafa was built by King Saul and destroyed by Pharaoh Shoshenq I.

Ignoring the emotional outburst of the introduction, the authors’ concept is quite simple: the city was built by one king who is mentioned in the biblical narrative and was destroyed by another king who is mentioned in the biblical narrative. This is precisely the old-fashioned approach of W.F. Albright, Y. Yadin, B. Mazar and Y. Aharoni, who freely associated kings and archaeological strata, even when lacking any hard evidence. Finkelstein and Fantalkin have no concrete data to justify associating Khirbet Qeiyafa with King Saul and they simply ignore the radiometric datings from Khirbet Qeiyafa that indicate the city was destroyed decades before Shoshenq I. As the authors are empty handed, and do not have any data to connect the site to either King Saul or Pharaoh Shoshenq I, they resort to rhetorical and demagogic measures. Their article clearly displays the symptoms of paradigm-collapse trauma—literary compilations of groundless arguments, masquerading as scientific writing through footnotes, references and publication in a professional journal.

The amusing title of this article: “Khirbet Qeiyafa: An Unsensational Archaeological and Historical Interpretation” is misleading. Is talk about a kingdom of King Saul less sensational than the idea of a Davidic kingdom? Aside from the Bible, do we know anything about King Saul? Is he mentioned in any extra-biblical source? Is there proof that he existed? Why is the biblical tradition of the kingdom of Saul more realistic than that of King David? In any case, we would be happy to unearth a royal inscription of King Saul at Khirbet Qeiyafa, and would be delighted to uncover a victory stele of Shoshenq I at our site. For the time being, however, we prefer to base our interpretation of the history of Khirbet Qeiyafa on the available evidence from our excavation, rather than engage in such wild speculation.

Following the publication of the above articles by Finkelstein and Piasetzky and Singer-Avitz, we submitted a response to Tel Aviv. It is standard practice for a journal that publishes criticism of a scholar’s work to print their response. This request was rejected by the editor, Professor Finkelstein. In lieu of a response in Tel Aviv, we responded to the attacks in an article in the Israel Exploration Journal (Garfinkel and Kang 2011). This appears to be a case of a scholar using his power as a journal editor to continue publishing articles against the Khirbet Qeiyafa excavations while censoring scholarly responses to these attacks. Finkelstein’s credibility as an objective and unbiased editor of a scientific journal is in jeopardy.

What emerges here is clearly an acute reaction to paradigm collapse, in which certain scholars are unable to deal with new data that challenge or invalidate their paradigm. I believe they have mistakenly ignored, distorted, and even manipulated the data, engaged in personal attacks, and have used their professional and editorial power in a questionable manner. The end result debases biblical archaeology.

As more and more data accumulated from our excavations, Professor Finkelstein’s position has become less and less plausible. He has tacitly admitted this by making a serious tactical retreat in the right direction. In 1996 he placed the beginning of the Kingdom of Judah in the late 8th century BCE, but recently argues that Judah became a kingdom at the end of the 9th century BCE (Finkelstein 2012), a hundred years earlier!

III. Khirbet Qeiyafa: An Unsensational Archaeological and Historical Interpretation

Any interpretation of the evidence from Khirbet Qeiyafa must consider the following facts (Garfinkel and Ganor 2009; Garfinkel, Ganor and Hasel 2010, 2011, 2012):

1. Location: Khirbet Qeiyafa is located at the western end of the high Shephelah and controls the entrance to the Elah Valley, the main route from the coastal plain to the hill country, Jerusalem, and Hebron.

2. New settlement: The city at Khirbet Qeiyafa was built on bedrock rather than over the ruins of a Canaanite city from the Late Bronze Age, unlike Late Bronze Canaanite cities, which are always built on top of Middle Bronze Canaanite cities. Why did this location suddenly become important in the late 11th–early 10th centuries BCE?

3. Massive fortifications: The site has an especially impressive casemate wall that incorporates megalithic stones weighing up to eight tons. Similar construction is unknown in Late Bronze Age Canaanite cities, nor is it evident at hundreds of smaller Iron Age I sites in the hill country (commonly known as “Israelite settlement sites”). The building tradition in Philistia used brick rather than stone, as can be seen from walls unearthed at Ashdod, Ashkelon and Ekron. Moreover, casemate walls are unknown in the Land of Israel in either Late Bronze Age Canaanite cities or Iron Age Philistine sites.

4. Two gates: Khirbet Qeiyafa has two gates, one in the west and the other in the south (Figs. 4–5). The gates are of identical size and consist of four chambers. This is the only known example from the Iron Age of a settlement with two gates in the Northern or the Southern Kingdom.

5. Urban planning: The dwellings at Khirbet Qeiyafa adjoin and are incorporated into the wall, with the casemate constituting the back room of every house. Such planning is currently evident at four additional sites: Beth-Shemesh, Tell en-Nasbeh, Tell Beit Mirsim and Tel Sheva. All these sites are dated to Iron Age II and are located in the south of the Land of Israel, in the Kingdom of Judah. In terms of its dating, Khirbet Qeiyafa precedes them all, attesting that this planning concept was already formulated in the late eleventh century BCE. Casement walls are also known at northern sites such as Hazor and Gezer, but at those sites, such walls are freestanding and do not abut dwellings.

6. Pottery vessels: The assemblage of local ware is relatively simple and includes a small number of vessel types: shallow rounded bowls, shallow carinated bowls, kraters with an inverted upper part and 2–6 handles, simple juglets, black juglets, simple jugs, strainer jugs, cooking pots with an inverted rim, baking trays, and storage jars that usually had a fingerprint on one of the handles. Most of the vessels lack ornamentation. Very rarely, red slip appears on a bowl or jug, which sometimes also features irregular hand burnishing. All these are typical characteristics of the pottery of the early Iron Age IIA (Garfinkel and Kang 2011).

7. Concentrated production of jars and the marking of their handles: Dozens of storage jars were discovered at Khirbet Qeiyafa, generally with one or more handles marked by a fingerprint. By the middle of the 2012 excavation season, about 600 such handles had come to light. Petrographic examinations indicate that all the jars originate in the vicinity of Khirbet Qeiyafa. This suggests the beginning of a central administration that was fully developed later, as attested by the royal (lmlk) jars.

8. Diet and food preparation: Thousands of animal bones were found at the site, including goats, sheep, and cattle. No pig bones were discovered. Almost every house contained a baking tray – a shallow bowl with a charred inner side, indicating that it had been placed over an open fire with the dough draped over the rough outer side.

9. Commercial ties: Finds from the site suggest the import of items from varying distances:

(a) 10–20 km away: Pottery vessels of the Ashdod Ware type were imported from Philistia. The ornamentation of these vessels typically includes red slip on the face as well as painted horizontal white and black lines. These relatively small vessels, with a volume of up to two liters, were apparently used to transport specialty products such as spices, medicines or special drinks.

(b) 100–150 km away: basalt vessels including both simple implements such as grinding stones and grinding plates as well as a finely crafted and polished bowl and a basalt altar decorated with a floral pattern.

(c) Cypriot imports: A number of pottery juglets that originated in Cyprus were discovered at the site. They are embellished with black bands and concentric circles painted on a white background. (Vessels of the black-on-red family characteristic of the late 10th century BCE were not found at the site).

10. Script: An ostracon found at Khirbet Qeiyafa contains five lines with a total of some 70 letters. The letters are written in an archaic style, in the Canaanite writing tradition (also known as proto-Canaanite script). A good deal of the writing is unclear, making it difficult to decipher. The inscription includes words such as “do not do” (al ta‘as), “judge” (shofet), “slave” (‘eved), el (god), Baal (Baal), and “king” (melekh). According to the epigrapher Haggai Misgav, based on the word ta‘as (to do), the language of the inscription is Hebrew. This is the longest extant inscription from the 12th–9th centuries BCE in the region.

11. Figurines: Three cultic rooms uncovered at Khirbet Qeiyafa contained an assemblage of ritual paraphernalia: stone altars, basalt altars, pottery libation vessels, shrine models, benches, basins and drainage installations, seals and scarabs. We found none of the human or animal figurines that are frequently found at Philistine or Canaanite ritual sites.

12. Dating: Based on 10 14Carbon readings of olive pits, the site dates to the late 11th and early 10th centuries BCE.

13. End of settlement: The site was destroyed suddenly, as attested by the hundreds of items found on floors or in the debris of collapsed buildings: pottery vessels, stone vessels, metal tools, scarabs and seals. Who destroyed the site?

14. Abandonment of the site: Khirbet Qeiyafa was abandoned following its destruction, and was not settled again until the late Persian period. Why did its inhabitants not rebuild the site, and why did it not become a multi-strata mound?

The data uncovered at Khirbet Qeiyafa clearly indicate that the site was occupied by a Judean population. Various characteristics of material culture uncovered at Khirbet Qeiyafa continue in the subsequent period at the classic sites of the kingdom, in layers dated to the 9th and 8th centuries BCE (Garfinkel, Ganor and Hasel 2011; Garfinkel 2011b, Garfinkel 2012):

1. Typical Judean urban planning, with casemate city wall and abutting houses.

2. Typical Judean cooking habits with baking trays and no pig bones. These are in sharp contrast to Philistine population.

3. Typical Judean administration with hundreds of impressed jar handles. This concept is well-known in the later royal (lmlk) jars and rosette jars of the 8th and 7th centuries BCE.

4. Cult rooms with an absence of cult images. This is in sharp contrast to the rich iconographic assemblages known from Canaanite and Philistine temples, or sites in the northern Kingdom of Israel.

5. Hebrew inscriptions.

The cumulative weight of the data indicate that the population of the site was not Philistine, Canaanite or people from the northern Kingdom of Israel. With its dating and location in the Elah Valley, the site marks the beginning of a new era: the establishment of the biblical Kingdom of Judah.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Jason Stanghelle for discussing various aspects relating to this article with me and for his careful editing of its text.

Figures

1. Aerial photograph of Khirbet Qeiyafa at the end of the 2011 excavation season.

1. Aerial photograph of Khirbet Qeiyafa at the end of the 2011 excavation season.

2. Map of the Iron Age city of Khirbet Qeiyafa, at the end of the 2011 excavation season. Note the casemate city wall, two gates, two gate plazas and houses. The openings of the casemates are always on the side farthest from the gate. Adjacent to each gate is a gate plaza. In the south, the gate plaza is situated to the left of the entrance while in the west it is situated to the right of the entrance. There is a cult room in each of the buildings bordering the gate plaza, situated next to the plaza. The biblical expression “gate bamot” may refer to this phenomenon.

2. Map of the Iron Age city of Khirbet Qeiyafa, at the end of the 2011 excavation season. Note the casemate city wall, two gates, two gate plazas and houses. The openings of the casemates are always on the side farthest from the gate. Adjacent to each gate is a gate plaza. In the south, the gate plaza is situated to the left of the entrance while in the west it is situated to the right of the entrance. There is a cult room in each of the buildings bordering the gate plaza, situated next to the plaza. The biblical expression “gate bamot” may refer to this phenomenon.

3. Ten 14Carbon dates were obtained from burnt olive pits found in the destruction layer of Khirbet Qeiyafa. The age determinations show that the city was constructed at Khirbet Qeiyafa in the second half of the 11th century BCE and existed into the 10th century BCE. The graph also shows (in the upper row) the average beginning date for all the samples and (in the lower row) an average final date for all of the samples. These averages enable us to establish the time limits for the existence of the city between 1020 and 980 BCE.

3. Ten 14Carbon dates were obtained from burnt olive pits found in the destruction layer of Khirbet Qeiyafa. The age determinations show that the city was constructed at Khirbet Qeiyafa in the second half of the 11th century BCE and existed into the 10th century BCE. The graph also shows (in the upper row) the average beginning date for all the samples and (in the lower row) an average final date for all of the samples. These averages enable us to establish the time limits for the existence of the city between 1020 and 980 BCE.

4. An Iron Age gate in the western side of the city.

4. An Iron Age gate in the western side of the city.

5. An Iron Age gate in the southern side of the city.

5. An Iron Age gate in the southern side of the city.

References

Dagan, Y. 2009. Khirbet Qeiyafa in the Judean Shephelah: Some Considerations. Tel Aviv 36: 68–81.

Finkelstein, I. 1996. The Archaeology of the United Monarchy: an Alternative View. Levant 28: 177–187.

Finkelstein, I. 2012. The Great Wall of Tell en-Nasbeh (Mizpha), The First Fortifications in Judah, and 1 Kings 15:16-22. Vetus Testamentum 62:14–28.

Finkelstein, I. and Fantalkin, A. 2012. Khirbet Qeiyafa: An Unsensational Archaeological and Historical Interpretation. Tel Aviv 39: 38–63.

Finkelstein, I. and Piasetzky, E. 2010. Khirbet Qeiyafa: Absolute Chronology. Tel Aviv 37: 84–88.

Garfinkel, Y. 2011a. The Birth & Death of Biblical Minimalism. Biblical Archaeology Review 37/3: 46–53.

Garfinkel, Y. 2011b. The Davidic Kingdom in Light of the Finds at Khirbet Qeiyafa. City of David Studies of Ancient Jerusalem 6:13*–35*.

Garfinkel, Y. 2012. The Settlement History of the Kingdom of Judah from its Establishment to its Destraction. Cathedra 143:7–44 (Hebrew).

Garfinkel, Y. and Ganor, S. 2009. Khirbet Qeiyafa Vol. 1. The 2007–2008 Excavation Seasons. Jerusalem.

Garfinkel, Y. and Ganor, S. 2010. Khirbet Qeiyafa in Survey and in Excavations: A Response to Y. Dagan. Tel Aviv 37:67–78.

Garfinkel, Y., Ganor, S. and Hasel, M. 2010. The Contribution of Khirbet Qeiyafa to Our Understanding of the Iron Age Period. Strata: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israeli Archaeological Society 28: 39–54.

Garfinkel, Y., Ganor, S. and Hasel, M. 2011. Khirbet Qeiyafa Excavations and the Rise of the Kingdom of Judah. Eretz-Israel 30: 174–194 (Hebrew).

Garfinkel, Y., Ganor, S. and Hasel, M. 2012. Footsteps of King David in the Valley of Elah. Tel Aviv (Hebrew).

Garfinkel, Y. and Kang, H.-G. 2011. The Relative and Absolute Chronology of Khirbet Qeiyafa: Very Late Iron Age I or Very Early Iron Age IIA? Israel Exploration Journal 61: 171–183.

Rollston, C.A. 2011. The Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon: Methodological Musings and Caveats. Tel Aviv 38: 67–82.

Singer-Avitz, L. 2010. The Relative Chronology of Khirbet Qeiyafa. Tel Aviv 37: 79–83.

Comments (17)

I come to this interdisciplinary feast with a background primarily in philosophy - and Anglo philosophy at that, rather than the exciting French kind. So perhaps I lack a wedding garment.

The idea of competing paradigms, or general attitudes to a research topic, arose from the work of Polanyi and Kuhn, who wished to resist the purely 'falsificationist' ideas of Popper. Popper, spurred by Hume's remarks about continuity over time, says that if your hypothesis predicts something that doesn't happen you must give it up and try another one, otherwise you cut yourself loose from reality. Polanyi, Kuhn and others, all somehow reflecting Kant, find ways of resisting the full stringency of Popper's demands: there are good reasons, they say, to stick for a while to a generally productive approach - Our Paradigm - even when it runs into anomalies.

I think most people would say in moderate terms 'maybe for a while but not for ever'. An implication of this moderate position would be that it's not so terrible for conflicting paradigms both to be pursued for a while. Maybe both - or all - the conflicting paradigms of Biblical Archaeology have had some predictive successes.

Thus far we may be irenic and accommodating, perhaps. On the other hand I don't think we can for ever escape the Popperian question 'What overall set of facts or discoveries would you accept as showing that your basic approach is wrong?'

There's also the slightly more congenial question 'What would constitute overwhelming anomalies facing the rival paradigm?' I would quite like to hear these questions answered by the contending schools of thought discussed here.

Even more basically, what exactly are these paradigms or basic propositions? We see an awful lot of rejection - 'you misunderstand!' - by everyone of propositions ascribed to them by everyone else. What do we take the Bible to say and with which of its alleged assertions is issue taken?

#1 - Martin - 07/28/2012 - 13:14

Part 1

It is symptomatic for Josef Garfinkel's response that his literature does not include just one work by these minimalists, only some articles by people from Tel Aviv University, mostly Israel Finkelstein. But Finkelstein is not a minimalist but sees his position as in the middle.

Accordingly and against his own idea about scholarship ("In order to test a scientific hypothesis first one gathers the data, then analyzes it, and finally arrives at conclusions") he does not collect any information about "minimalism" before he makes his assumptions about it. So his attack on minimalism is uninformed. He brings in some old horsed like the Siloam-debate from the mid 1990s, and makes it a symbol for the whole direction of minimalism, although only one minimalist supported the idea and has later left it. The Tel Dan Stele (not "several fragments" but only three!): Garfinkel mentions without precise reference a few contributions to the debate from the mid-1990s (was this the moment when he gave up reading anything?). What happened since then he simply ignores. But to accept the problems with this inscription, such as the letter in the top line that goes down the broken side, are ignored. My conclusion from about 2000 that sufficient evidence has not been procured to persuade people who believe in the inscription as genuine still stands.

In total his attack on minimalism, which is so ill-informed that it will be ignored, reminds me of a line in James Barr's Fundamentalism from 1977: Don't read Wellhausen. Read (conservative) books about Wellhausen.

His hanging the minimalists out as being influenced by post-modernism is simply nonsense. There are studies that have shown that minimalists have been pretty modern, and their thinking modern. Post-modernism came later. It is revealing for the standard of discussion about the origins of Judaism that is found in some quarters in Israel, which totally ignores hermeneutic changes in the world at large. Rather than representing modern scholarship, Garfinkel seems to belong the dinosaurs of the past.

Most of the article has to do with the running controversy between the archaeologists from Tel Aviv and those from the Hebrew University. This part of the debate I will leave to the specialists, although I have similar reservations to the idea of Saul as the prime mover as Garfinkel seems to have.

#2 - NPLemche - 07/28/2012 - 14:42

Part 2

What Garfinkel has no idea about, is the ongoing debate of history and cultural memory. The Bible is representing cultural memory if anything, and provides a foundation legend for the Jewish people. Memory is not obliged to keep the facts strait. Modern history is, but this was hardly the demand in ancient times (read Herodotus and the debate about him already found in ancient literature). As cultural memory the Hebrew Bible represents sentiments and "memory" belonging to the time when the various books were reduced into writing. That it was not in the 10th century (Gerhard von Rad redivivus) is almost everywhere accepted by biblical scholars.

Garfinkel is living in a world that is no more. Scholarship has changed almost everywhere. The German-like methods he defends are not even in vogue in Germany anymore. Biblical archaeology is a discipline with a lot of problems. Although Hershel Shanks claims that I argue that biblical archaeologists are "low life" (recently in BAR), I did not state that but it was a conclusion that came into mind reading the introduction to a Scandinavian archaeologist and the reactions to his study on biblical archaeology as a waste of time. The Scandinavian archaeologist found that a waste of time, and Garfinkel must know that our archaeological tradition is second to none (beginning with Wilhelm Thomsen, who got the idea of dividing the past into the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages). The reason was epistemology, and that biblical archaeology was here displaying ideas from the past and some "Blut und Boden" ideology which is really disturbing. In Ben Gurion's days, archeologists were the servants of his dreams about an exclusively Jewish state. I believe this has changed in many ways in modern Israel, but it is still the job of national historians and archaeologists to write national history.

NP

#3 - NPLemche - 07/28/2012 - 14:42

NPLemche began his comment by criticizing Garfinkel for his lack of (academic) literature citations. I can't help but wonder if he has any citations (academic or popular) to back up his statement that "archeologists were the servants of [Ben Gurion's] dreams about an exclusively Jewish state." Personally I can't think of any of the major early-20th-century excavators who qualify.

NPLemche also believes the Bible "provides a foundation legend..." Again, I doubt he can provide any scientific basis for this overtly subjective statement. He's essentially demonstrating Garfinkel's point about critics "creating a purely imaginary mythological-literary history."

One point upon which I doubt Garfinkel, is the allegation that Finkelstein rejected his Tel Aviv Journal rebuttal (to protect his bias). I have no problem believing all the miracles recorded in the Bible, but have a hard time believing Finkelstein is a biased editor, or that his editorial credibility is in jeopardy.

#4 - G.M. Grena - 07/29/2012 - 04:05

This is poor stuff. I note merely that for the third time,despite being told otherwise, he asserts that the Tel Dan steal mentions a king of the house of David, which is incorrect. The word king is a conjecture. Someone who believes that a factual correctness is not important should keep quiet abut scientific method.

#5 - Philip davies - 07/29/2012 - 08:24

@Grena

Malamat in his youth belonged here. I have one of the titles from these meetings. I always had a good relationship to Malamat so I trusted what he said about the sociology of scholarship in Israel.

As to the second statement of Mr Grena, I have written I believe thousands of pages about this so I don't find it necessary to document more than I have already done. So Mr Grena, the market is free for you to look for yourself.

That you as little as Garfinkel has any idea of what is going on when it comes to modern historians and their interpretations is a sad fact. Read LeGoff, Pierre Nora, or for that matter Ricoeur, Derrida, and their critics... just in case that you missed something.

You should also read a few things by Liverani, such as his study of the letters of Rib-Adda. Instead of doing the relevant readings you proceed with these stupid mantras of past scholarship. Thus Garfinkel's methodology, his approach to interpretation is simply something belonging to the past. It is not a matter of being post-modern or not, it is simply a matter of being part of the world today.

Nothing is simple.

NPLemche

#6 - Niels Peter Lemche - 07/29/2012 - 20:47

Dear NPLemche, can you provide an independent, contemporary document that substantiates your assertion that "Malamat in his youth" acted in the capacity of a servant to Ben Gurion in the role of an archeologist for an exclusively Jewish state, presumably by directing a significant excavation at a time when so many British, American, & European teams were given permission to excavate by the same archeological authority? If so, which site(s) did he excavate? Who funded his excavations? Or are you just, in the words of Garfinkel, "creating a purely imaginary history"?

Dear Philip davies, thanks for commenting on the scientific method. Since the Dan Stela fragments contain 4 instances of the word for king ("MLK"), AND since these fragments represent only a small portion of the original text, AND since one of these instances appears with the name "Israel" in the line immediately above the phrase "House of David", AND since the exact phrase "BYT DVD" appears 14 times by multiple OT writers in the context of kings of Judah (& Israel), Garfinkel's "conjecture" is scientifically rational. You, on the other hand, are guilty of the Special Pleading fallacy because I'm sure you don't hold other inferences to the same level of skepticism (e.g., since you don't believe the Bible contains a revelation from God, you probably believe the first forms of life came from non-life, for which there is no scientific evidence whatsoever). Please correct me if I'm wrong (& please don't embarrass yourself further by committing an Argumentum ad Populum fallacy).

#7 - G.M. Grena - 07/30/2012 - 05:17

Mr Grena,

Isn't wonderful that you have found a forum where you can continuously offing the establishment!

We--the professionals owe you no explanation of anything. You will never join a peer review committee taking up for a review anything we have written.

For this time, you can get an answer, and I would like to see your reaction: Next to me I have a little book published in 1964 by Malamat, Organs of State Craft in the Israelite Monarchy, Jerusalem 1964:

It has the following introduction:

"The following lecture was presented on Aug. 22, 1963 by Prof. Abraham Malamat at a meeting of the Bible Study Circle in the home of the former Prime Minister, Mr. David Ben-Gurion and with the active participation of the President of the State of Israel, Mr. Zalman Shazar. The meeting was presided over by Justice of the Supreme Court Prof. M. Silberg. We present herewith the lecture and accompanying discussion (as translated from the Hebrew), with a few minor changes and some additional footnotes.

I see no further reason to continue this debate with you, and your attack on Philip Davies as a non-believer in your version of the Gospel (or whatever it is) is extraordinary (to phrase it mildly). I don't understand why your message was accepted.

In other list of scholars you would have been banned from them because of such a mail..

Niels Peter Lemche

#8 - Niels Peter Lemche - 07/30/2012 - 15:40

If the law of conservation of matter applies then each life form comes either from other earlier ones, ie by evolution, or from inanimate matter acquiring a new role, perhaps because God breathes the breath of life into it. Whether either of these developments, astonishing to the human spirit as both are, would actually be a demonstration of divine providence is a question that many would regard as beyond the reach of science, since there are no crucial experiments to test it. (My 'many' would include Karl Popper and Charles Darwin at least in some moods.)

Are there crucial experiments to test rival theories of biblical history, making the evaluation of these theories a genuinely scientific matter? If so, what are they and what gives them their crucial status?

I'd be sorry to see this discussion become a discussion of the intellectual history of Zionism and anti-Zionism, which can be discussed elsewhere. However, I don't think there's much doubt that our views of history(I mean the views of all of us) are influenced by our view of politics.

There really is a distinction between a plausible conjecture and an observed fact. This distinction is rather crucial to Popper-style philosophies of science. I must say, getting away from my partial comfort zone in philosophy, that I think it overwhelmingly plausible to suppose that there was a House of David in the relevant place and time: but of what that implies I am not, for what that's worth, so sure.

#9 - Martin - 07/30/2012 - 16:28

As Martin pointed out this is not the proper venue to discuss Zionism or modern nationalism. It is Lemche and his ilk who drag this constantly into the discussion of Early Israel.

NP Lemche wrote "In Ben Gurion's days, archaeologists were the servants of his dreams about an exclusively Jewish state." and "Malamat in his youth belonged here."."

G M Grena challenged him about that, asking him to show evidence that Malamat conducted any excavations.

Since Malamat was not an archaeologist Lemche didn't have such evidence. Instead he cited M.'s participation in BG's well known biblical discussion group.

As for the rest of his answer to G M Grena - a noticeable feature among the minimalists is their ad hominem attacks on those who do not take their positions seriously.

Is this a manifestation of their religious anti-biblical dogmatism?

Since Lemche proudly applies the term 'Fundamentalist' to some of his critics, he surely would not mind being called a 'dogmatist'?

Since Lemche said he was a friend of Malamat and accepted his opinions on Israeli scholarship, why did he not also learn fromn Malamat his valid approach to Early Israel based on thorough knowledge of Mesopotamian sources? And after doing that, he could do the same with regard to Kitchen and his very thorough knowledge of Egyptian sources?

Uri Hurwitz

Uri Hurwitz

#10 - Uri Hurwitz - 07/30/2012 - 19:07

Dear Dr. Lemche, you picked a bad time & place to brag about the honor of being on a peer-review committee (for reasons not directly related to our current discussion, but they'll be obvious after the next issue of Tel Aviv gets published; for now I'll refer BI readers to my August 2010 "Considering" article). Thank you for the published reference from 1964 documenting that Malamat was one of multiple archeologists serving Ben Gurion's dreams, unlike the many archeologists that preceded "Ben Gurion's days" who excavated objectively, not knowing what they would find. I stand corrected, & you are under no obligation to ever respond to me again. I do not have a copy of the booklet (none for sale or in local libraries), but I trust you that it not only proves your point, but proves that I was mistaken to challenge your statement as if it were some sort of non-scholarly, anti-Semitic hyperbole.

Dear Martin, the law of conservation of matter cannot account for the appearance of matter (or anti-matter for that matter as a matter of fact), so it cannot inform us about the origin of life since life is obviously beyond the realm of matter. Why? Because immediately after something dies, it consists of the exact same matter (including DNA) before it died, yet it's very different, isn't it? Animate matter can acquire inanimateness (death), but not vice versa.

#11 - G.M. Grena - 07/31/2012 - 04:42

Mr Grena probably does not know classical Hebrew or Akkadian. If he did, he should know that the formula mlk plus byt plus name never occurs in any text in an ancient Semitic language. We never get, for example, mlk byt )mry. But if he wants to follow an argument that assumes byt dwd refers to Judah, he can read my own recent work on this. Since no king or kingdom of Judah is mentioned in Akkadian or Palestinian texts until the 6th century, it seems scientific to doubt that it existed as such. We certainly have melek plus ysr)l in the Tel Dan stela, so why not mlk yhwdh? Don't we think this is something worth exploring instead of explaining away (which is the standard fundamentalist route). On the Siloam inscriptiion, I see that Reich and Shukron now want to date it a century earlier than Hezekiah, which poses serious problems for traditional epigraphy ad for historical scenarios. Do keep up with your reading, please! And suppress your reactionary instinct in favour of some critical reflection. You might then be taken more seriously.

#12 - philip davies - 07/31/2012 - 07:37

Genesis or birth is the process (so long as there's conservation of matter) whereby matter is gathered and made to work in a certain organised form, destruction or death is when that organising form ceases to operate. In advanced organisms the blood and the breath that were moving are now still. Hence Aristotle's dictum that the soul is the form of the body.

Perhaps you and I, Professor Grena, think that there is more to the soul than this and that divine providence is at work in matters of genesis and destruction.

For the definition of science, which is a central topic on this thread, I think we should attend to the difference from things that can be scientifically tested and things that cannot. People conventionally test for life vs. death by looking at the movement or stillness of blood and breath: that is a physical and scientific test. Whether the soul flees to heaven and whether God will wipe away all our tears are questions for philosophical, religious and poetic, not for scientific debate.

Some of the ancients drew elaborate analogies between individuals and societies. Certainly both are organised beings. The debate about Biblical History is presumably a scientific debate about whether particular forms of human organisation existed and about what records and what traces there are. At least I still hope it's that and not an exchange of religious polemics. For the purposes of scientific debate I would still like to ask the Popperian question. What would show each of the different views to be mistaken?

Look! I've got back to the original topic. Well, you may not agree.

#13 - Martin - 08/01/2012 - 15:03

To Davies #12. You wrote " Since no king or kingdom of Judah is mentioned in Akkadian or Palestinian texts until the 6th century, it seems scientific to doubt that it existed as such."

From Sennacherib's Prism As for Hezekiah the Judahite, 19who did not submit to my yoke: forty-six of his strong, walled cities, as well as 20the small towns in their area,... Hezekiah) himself, like a caged bird 28I shut up in Jerusalem, his royal city.

I guess Judean history begins in the 8th century now?

#14 - Jose Castro - 08/05/2012 - 15:57

Now Judahite is an ethnicon and not a political name, just to set it right. So Davies is still right. There is no mentioning of a state called Judah in the 7th century (my old teacher in Akkadian Trolle Larsen translates it as "Jew", "Hezekiah the Jew"). In the Wiseman chronicle about the conquest of Jerusalem in 597, the name of the city is not mentioned but it is substituted by "the city of Judah". Here Judah is presumably a political name.

This does not mean that there was no Judah in the 8th or 7th century only that Judah is not attested as a political name. In Sennacherib's annal it could be a geographical name, saying that Hezekiah was from Judah, although most will be satisfied with the simple solution that he was from the state of Judah.

NPLemche

#15 - Niels Peter Lemche - 08/07/2012 - 05:06

Not so fast.

And this from Sennacherib.

"I devastated the wide province of Judah, the strong proud Hezekiah, its king, I brought in submission to my feet." Luckenbill AR 2 148 from

Hallo, William W., James C. Moyer, and Leo G. Perdue. Scripture in Context II: More Essays on the Comparative Method. Winona Lake, Ind: Eisenbrauns, 1983, 149. Don't have access to Luckenbill to check.

#16 - Jose Castro - 08/07/2012 - 07:06

Checked it,

rap-šú na-gu-ú lIa-ú-di: Luckenbill The Annals of Sennacherib p. 77.

You are right, in 701 Judah more than a city, I suppose that "l" stand for mat.

NPLemche

#17 - Niels Peter Lemche - 08/07/2012 - 18:48