Mesopotamian Ruins and American Scholars

Two Years Later: Some Lobbying Successes But the Devastation of Iraq's Cultural Heritage Continues

By Francis Deblauwe

The 2003- Iraq War & Archaeology Project

August 2005

After the conquest of the Iraqi capital Baghdad in April 2003, the world witnessed in astonishment and shock as the National Museum was looted and vandalized for several days while the US military did not lift a finger to protect it. This museum is the premier repository of Mesopotamian artifacts of which it holds the largest collection in the world. Even more importantly though, these are mostly excavated and documented pieces, indispensable for true archaeological research, unlike many in other museums that are without clear provenance or context. In the end, the Museum was secured and through the efforts of Iraqi police, US and Coalition law enforcement, and international efforts some of the stolen artifacts were recovered. Especially noteworthy was the return of the Lady of Warka sculpture, the Warka Vase, and the Bassetki statue. An estimated 13,000 pieces are still missing. The many tens of thousands of archaeological sites throughout Iraq have not been so lucky: their looting and destruction has not even begun to abate since 2003. The Sumerian heartland in southern Iraq has been hit the hardest. Whole "tells" or ruin mounds have been reduced to pockmarked moon landscapes due to the frantic digging activities of looters, e.g., Tell Jokha (ancient Umma), Ishan Bakhriyyat (ancient Isin), etc.

The reaction in the US to the events of 2003 has been mired in controversy. After the intial confusion in the media during which it was feared the National Museum had been robbed bare, a number of conservative, pro-Iraq War political commentators falsely claimed that hardly anything had been taken. In other words, the museum theft story supposedly had been just a ploy by Ba'athists to make the Bush administration look bad. Western archaeologists and scholars had been either willing or naïve participants in this fraud, so it was said. It is hard to believe but this myth is still being repeated every so often. In general, the US academic community reacted with horror and anger. Notwithstanding serious pre-war efforts to educate both the Pentagon and the State Department about their responsibilities toward the heritage of Iraq once the war would begin, it was apparent that the commanders on the battlefield had not been instructed to safeguard archaeological and cultural sites. The one positive effect from the consultations was that Coalition airplanes did manage to avoid bombing sensitive heritage sites.

Once the damage to the National Museum, the tells of Mesopotamia and other parts of Iraq's cultural heritage became apparent, scholars redoubled their lobbying efforts with the US Congress. Many professional organizations ranging from the Historians of Islamic Art to the American Anthropological Association, the American Association of Museums, and the American Library Association passed resolutions and other statements of concern. Never before were so many Assyriologists interviewed by the national media. The Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) led the charge to try to close as many of the legal loopholes as possible. Initially, it supported the "Iraq Cultural Heritage Protection Act" (proposed by Rep. Phil English) in the US House of Representatives over the weaker "Emergency Protection for Iraqi Cultural Antiquities Act of 2003" (by Sen. Charles Grassley) in the US Senate. However, for reasons of political strategy and expediency, both were dropped in favor of a combined Senate/House "Emergency Protection for Iraqi Cultural Antiquities Act of 2004" which the AIA was instrumental in helping to become law in November 2004. This law gave the US President the authority to impose restrictions to prevent the import of cultural materials that had been illegally removed from Iraq since August 1990. Substantial resistance from collector and antiquities dealers interest groups had to be overcome, but the momentum was on our side this time.

Mesopotamian archaeologists and other concerned academics have fortunately been lucky to enjoy a surge of support for their cause among the American public at large, especially in 2003. I have contributed to this by starting in early April 2003 a web site called "The 2003- Iraq War & Archaeology" (http://iwa.univie.ac.at). It has offered and still provides a balanced, knowledgable and exhaustive but still accessible one-stop reference place for documentation and information to scholars, policymakers, and journalists as well as the interested public. The main part consists of reviews/summaries of web articles (published in English, French, German, Dutch, Italian, etc.) and other information with the occasional comment or annotation. I have been updating it almost on a daily basis for two years now, archiving articles as I went along. In light of the confusion surrounding the looting of the National Museum early on in 2003, I included an educated guess of the losses to offer some common-sense guidance. I base this on all the sometimes contradictory and constantly changing information available publicly as well as via private channels. Later, I added a list of archaeological sites that are known to have been looted and/or damaged (currently at least 37). These quickly became the numbers of reference for a lot of journalists. I have also given many interviews by and responded to umpteen requests for information from journalists. There have been times when I was really touched by some of the reactions, e.g., T. & S.F., personal e-mail, May 25, 2003: "Thank you so much for maintaining your fantastic website ... My wife and I are following your postings closely, and especially your estimate of the scale of damage to the National Museum, now thankfully down to 8% loss. Compared to the 100% early estimates, which had Susan in tears for several days and myself in a dumb fury, your objective appraisal has done much to calm us down and enable us to focus on the reality of the situation, which is still so extremely horrific but at least *comprehensible*."

The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago has been very active in US academia proper concerning the efforts to protect the heritage of Mesopotamia in these times of calamity. In April 2003, Dr. Clemens Reichel's team started the "Lost Treasures From Iraq" web site (http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/iraq.html). It contains a growing database of the artifacts of the National Museum in Baghdad to help in the recovery of the missing objects and to use as an educational resource for schools and the general public. Each artifact is briefly but expertly described and illustrated. As of April 19, 2005, a total of 1,150 items had been entered and work is ongoing. The site also provides photographs of Iraqi archaeological sites, bibliographies, etc. His colleague Chuck Jones has been moderating a mailing list, "Iraqcrisis," which has greatly facilitated the exchange of information and the discussion of strategies between archaeologists/historians/linguists and librarians/conservation specialists/heritage experts, between Mesopotamian and Islamic specialists, between academics, government/military and private-sector people.

The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago has been very active in US academia proper concerning the efforts to protect the heritage of Mesopotamia in these times of calamity. In April 2003, Dr. Clemens Reichel's team started the "Lost Treasures From Iraq" web site (http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/iraq.html). It contains a growing database of the artifacts of the National Museum in Baghdad to help in the recovery of the missing objects and to use as an educational resource for schools and the general public. Each artifact is briefly but expertly described and illustrated. As of April 19, 2005, a total of 1,150 items had been entered and work is ongoing. The site also provides photographs of Iraqi archaeological sites, bibliographies, etc. His colleague Chuck Jones has been moderating a mailing list, "Iraqcrisis," which has greatly facilitated the exchange of information and the discussion of strategies between archaeologists/historians/linguists and librarians/conservation specialists/heritage experts, between Mesopotamian and Islamic specialists, between academics, government/military and private-sector people.

Prof. Elizabeth Stone (Stony Brook University, New York) headed the component of the USAID-Iraq HEAD program that was tasked with developing and enhancing archaeological studies and practice in Iraqi universities. In the summer of 2004, a training workshop was held in Amman for 55 Iraqi faculty, graduate students, and members of the Department of Antiquities. The goal was to allow them to catch up with developments in their fields that have taken place over the past two decades when they were cut off from the world beyond Iraq. Several Iraqi students also were given the opportunity to come and study in the US. The one-year program was unfortunately not renewed. Furthermore, a comprehensive project intended to gather and bring online cuneiform texts, the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI; http://cdli.ucla.edu) had already been initiated in 2000 by the team of Prof. Robert Englund (University of California, Los Angeles) and Dr. Peter Damerow (Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Berlin). These written documents have always been infuriatingly scattered all over the world and hard to access for research. Even the largest and most important collections, i.e., the cuneiform tablets of the National Museum in Baghdad, the British Museum in London, and the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul are very incompletely published. The CDLI therefore presented a giant step forward in making a large corpus of Mesopotamian texts widely available for free through an intuitive database interface on the web. Fortunately, as far as we know, the superb cuneiform-tablet collection survived the looting of the National Museum in Baghdad almost intact. As of May 6. 2005, the CDLI includes as many as 7,610 cuneiform documents from the Museum.

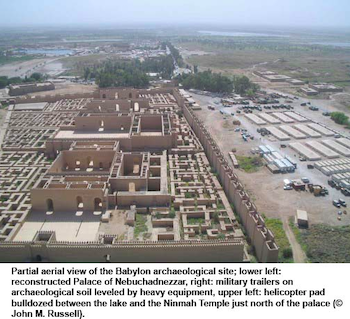

Special mention goes to Prof. John Russell (Massachusetts College of Art, Boston) and Prof. Zainab Bahrani (Columbia University, New York) who, in succession, from 2003 to 2004 served as Senior Advisors to the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) and the Ministry of Culture in Iraq. They spoke up on behalf of the cultural heritage of Iraq with the Coalition military and bureaucracy. They also were crucial for improving communication between the CPA and the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH) of Iraq and facilitating contacts with international cultural donors and sponsors. The circumstances under which they had to work were however deteriorating steadily and their Dutch successor, René Teijgeler, has not been replaced since he left early this year. Volunteers to risk life and limb in Iraq are hard to come by. Nowadays, all a Western archaeologist ends up doing is sitting around in his/her Baghdad hotel and hoping (s)he does not get blown up on his way to a meeting with Coalition, SBAH, or other Iraqi government officials. The National Museum is closed down shut, awaiting better days. Venturing out to archaeological sites out in the desert is tantamount to asking to be kidnapped. Not exactly the stuff academic dreams are made of! So this leaves us here in the safety of our homes with 24-hour electricity and water–unlike in Iraq–to plan for the future, a better future that surely must come around some day for Iraq. The Getty Conservation Institute and the World Monuments Fund have joined forces in an initiative aimed at training Iraqis to conserve, manage and protect their heritage sites according to the latest technology and methods. They too organized training seminars in Amman (Jordan). The American Association of Museums is involved in a program whereby staff of the National Museum in Iraq will come for study trips to US museums, and so on.

My own 2003- Iraq War & Archaeology web site has endured all this time, growing in volume, even though it has remained essentially a one-man endeavor without institutional support. Then in April, it was pulled from the web without warning. After tedious inquiries, I found out that the root cause was a threat of legal action by a lawyer representing a New York antiquities dealer. He had claimed that I was defaming his client by quoting a defamatory statement contained in an article published on a web site in the Netherlands. As readers of my site will know, I routinely excerpt sections of English-language articles, clearly marked with quotes. On every page of my site, I state that inclusion of an article does not necessarily mean that I agree with the content. Said article accused the dealer of smuggling a Neo-Assyrian relief stolen in Iraq into the US. I did not express an opinion on whether or not this accusation were true–I have no way of knowing. I try to offer a complete picture of the situation of archaeology in Iraq, warts and all. This means that I frequently include articles that contradict one another or are not always likely totally accurate. Due to the dearth of good, verified information from Iraq, I include some of this anyway within reason, and sometimes with an "editorial" comment when I am able to shed some light. In reaction, the university that hosted my site (University of Missouri) invoked a technicality to discontinue our relationship. I am happy to report that the Institut für Orientalistik of the University of Vienna (Austria) gallantly offered to host my site, an offer I gratefully accepted. I have learned that at least one more academic web site that had material referring to the same Dutch article purged this material after also receiving threats from the same lawyer. Another site chose to pre-emptively pull similar material before getting into any trouble. As I am not a lawyer, I cannot evaluate the validity of this legal complaint but the comments I have received seem to leave a lot open to interpretation. In other words, even though in my specific case, it could probably be argued that I should be allowed to post the way I did in the context of my site, the said lawyer, using the deep pockets of his client, could still take me to court. I would have to pay for legal representation and waste a lot of effort and time, effort and time I could not dedicate to keeping the plight of Iraq's archaeological heritage in the spotlight. And you could never be sure about the verdict, could you?