Indications that the "Brother of Jesus" Inscription is a Forgery

By Jeffrey R. Chadwick

Associate Professor of Church History

Brigham Young University

jrchadwick@byu.edu

November 2003

Dr. Jeffrey R. Chadwick's essay, "Indications that the "Brother of Jesus" Inscription is a Forgery," was an early scholarly analysis of the so-called James ossuary inscription, written within a few months of the Ossuary's announcement to the world. Dr. Chadwick first submitted the essay for publication to Hershel Shanks' magazine, Biblical Archaeology Review. Although the magazine turned down the essay, Mr. Shanks argued against it in his book The Brother of Jesus, which he co-wrote with Dr. Ben Witherington III. Dr. Chadwick's essay has never been released to the public, so Bible and Interpretation offers it to the world here for the first time.

Article follows.

The so-called "Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus," first publicized in the popular magazine Biblical Archaeology Review,1 has gained world-wide notoriety as an archaeological artifact supposedly connected to Jesus of Nazareth. Mentioned in newspapers and magazines around the globe, it was featured in an hour long Easter program on cable television's Discovery Channel,2 and is the subject of a new book entitled The Brother of Jesus co-authored by Hershel Shanks,3 the editor of Biblical Archaeology Review. Were it not for the active involvement of Shanks, a dynamic individual who has arguably had as great an impact on the field of biblical archaeology as anyone now living, this ancient artifact would not be nearly as well known as it now is.

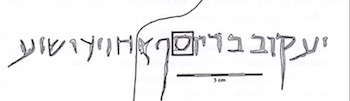

There can be no doubt that the 21 inch long carved limestone container is an authentic first century C.E. ossuary (bone box) which originated in the Jerusalem area. Nor can there be any doubt concerning the authenticity of the eleven letter Aramaic inscription on one of its broad sides reading Yakov bar Yosef— in English "Yakov son of Yosef." But I am convinced that a later addition to the inscription, tentatively identified as the Aramaic words ahui d'Yeshua, or "brother of Jesus," is a demonstrable forgery.

The combination of the original eleven letter inscription and the nine letter forged addition make a twenty letter phrase supposedly reading (in King James English) "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus." [An original drawing of the inscription appears at the top of this page.4] If it could be authenticated in its entirety, the impact of such a find would be spectacular. The discovery of a genuine first century written reference to Jesus of Nazareth and two other New Testament personalities would be of unprecedented significance in evaluating the historicity of Christian origins. But upon close physical examination, or even from the excellent photographs which appeared in Biblical Archaeology Review, two things are evident: (1) The pointed instrument that scratched the last nine Aramaic letters onto the ossuary was not the tool that carved the first eleven, and (2) the hands that formed the letters identified as ahui d'Yeshua or "brother of Jesus" were not the same ancient hands that carefully engraved Yakov bar Yosef . I will examine evidence for these conclusions below. But first, a word about the source of the find.

By now it is widely known that what I choose to call the "Yakov bar Yosef ossuary" is part of a private antiquities collection assembled by Oded Golan of Tel Aviv, Israel. Golan, an amateur archaeologist, attempted for a time to keep his identity anonymous. He possesses a large number of ancient artifacts purchased over many years from antiquities dealers all over Israel. Golan claims to have obtained the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary from a Jerusalem dealer sometime before 1978, but there is wide-spread suspicion that he obtained it much more recently. In either case, it is certain that the ossuary was not discovered as part of a legitimate archaeological excavation. It was, in fact, looted from an ancient tomb by modern antiquities thieves, and its original archaeological context and condition cannot be ascertained. Nor are the details known of just how the forged inscription was produced (although suggestions about this will be made later in this report).

Golan met French scholar Andre Lemaire in 2001 at a private party in Israel. After seeing photos of the ossuary, Lemaire concluded that the inscription must refer to the James in the New Testament who is called "the Lord's brother."5 Physical inspection of the ossuary itself confirmed this conclusion to Lemaire, and the result was his startling article in Biblical Archaeology Review of November 2002, claiming the discovery of an authentic first century C.E. inscription mentioning three New Testament personalities — Jesus of Nazareth, Joseph the husband of Jesus' mother Mary, and James (properly Yakov or "Jacob") the supposed "brother of Jesus."

After its initial publication, the ossuary was taken to Toronto, Canada and displayed at the Royal Ontario Museum in November of 2002 at the same time the American Schools of Oriental Research, the Society of Biblical Literature, and the American Academy of Religion were having their annual conventions in Toronto. It was during this exposition that I was first able to examine the inscription at close range, along with many other scholars. Unfortunately, when the ossuary was shipped from Israel to Canada, preexisting cracks in its limestone were aggravated, creating several breaks in the stone box. One break extended right through the inscription — ironically, right through the forged part. The breaks and cracks were repaired by conservators at the Royal Ontario Museum. However, the masking of the breaks obliterated one of the letters of the inscription (the alleged dalet), so that it is now necessary to refer to photographs of the inscription taken before November 2002 in order to completely evaluate its authenticity. (I recommend the close-up photograph of the inscription that appeared in Biblical Archaeology Review of November 2002, pages 26-27.) Upon its return to Israel in March of 2003, the ossuary was seized by the Israel Antiquities Authority, which is investigating Oded Golan in connection with a number of alleged irregularities concerning pieces in his collection.6

The epigraphic indications of forgery

In order to explore the epigraphic indications that the "brother of Jesus" portion of the inscription is a modern forgery added on to an authentic ancient inscription, it is necessary to engage in a far more detailed discussion of the actual shapes of all twenty letters of the inscription than has previously occurred. Lemaire himself explained that "details in the shape and stance of the letters are exceptionally important," and that "a mixture of letter shapes from different periods or different scribal traditions is a dead giveaway that an inscription is a fake."7 In the case of the ossuary in question, differences are stark between letter shapes of the original eleven letter inscription and the letter shapes of the nine letter addition. Upon careful comparison it becomes obvious that the person who formed the letters of the original Yakov bar Yosef portion of the inscription was not the same person who created the letters identified by Lemaire as ahui d'Yeshua or "brother of Jesus."

The person that inscribed Yakov bar Yosef was very careful in the formation of each individual Aramaic letter, and appears to have observed a set of rules in executing his letters, such as precise creation of angles, horizontal and vertical lines, careful sizing of yods, and extending of vavs. He was careful not only in the formation of each individual Aramaic letter, but also in duplicating his letters. Take his creation of the letter bet for

![where two bets are seen side by side [fifth and sixth letters from right] the bet denoting "v" at the end of Yakov [fifth from right] and the bet at the beginning of bar or "son" [sixth from right] are nearly identical](/sites/bibleinterp.arizona.edu/files/content/images/ip%202.png)

example. As seen in the figure above, where two bets are seen side by side [fifth and sixth letters from right] the bet denoting "v" at the end of Yakov [fifth from right] and the bet at the beginning of bar or "son" [sixth from right] are nearly identical, featuring not only the small upward serif at the left-hand side of the top line, but also a carefully measured tag or "tittle" which extends slightly to the right of the perpendicular meeting point of their vertical and bottom horizontal lines.

There are two other repetitions of letters in the original inscription — two yods and also two vavs. In each case, the ancient engraver made the second occurrence of these letters look similar to the first. The yod that is the first letter of the name Yakov [far right in the figure below] is same size as the yod that is the first letter of the name Yosef [second from right]. Though the downstrokes of both yods are perfectly vertical, the two letters are only half the vertical height of other letters in the name phrase, and there is a visible attempt at a serif at the top of each. By comparison, the

yods in the "brother of Jesus" addition are quite dissimilar. The yod of Yeshua [far left in the figure above], while handsomely created, is acutely diagonal rather than vertical, and extends well below the halfway point at which the yods of Yakov and Yosef end. The yod [second from left] in the word Lemaire identifies as "ahui" or "brother of" is also somewhat longer than the yods of Yakov bar Yosef, shows no attempt at a serif, and is indeed as different from the yod of Yeshua as it is from the yods of both Yakov and Yosef. In a short inscription of only twenty letters, for there to be no continuity of shape between the yods of the first part of the inscription and the yods of the second part of the inscription must be regarded with suspicion.

Consider also the four vavs of the inscription. The vav that serves as the "o" of Yakov [far right in the figure below] and the vav that serves as the "o" of Yosef [second from right] are both perfectly vertical, with serifs at their tops, and both extend slightly below the baseline of other letters in the phrase. By contrast, the vavs of "ahui" and Yeshua are notably different. Thevav of Yeshua [far left in the figure below] does not extend

below the base line of other letters, as do the vavs of Yakov and Yosef, and the attempt at a top serif is weak and indistinct. The vav of "ahui" [second from left] lacks any attempt at all of a top crown or serif, and extends only very slightly below the baseline, probably due to the fact that it was made with two different cutting strokes (more on this later). Even the untrained eye can detect the significant differences of shape between the two sets of vavs, differences that should not exist in a short, carved stone inscription performed by a single hand.

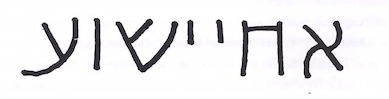

Stark differences also appear upon close examination of the letter ayin as found in Yakov and in Yeshua. The ayin that represents the "a" sound of Yakov [right side letter in figure below] was cut with its two upper lines extending in different diagonal directions, the right side line pointing diagonally upward to the right, and the left side line pointing diagonally upward toward the left. The right side line makes an oblique corner turn into its lower extension, and where the left side line intersects with the lower extension of the right side line, it does so at a perfectly perpendicular angle. By contrast, the handsomely cut ayin that represents the "a" sound

![[left side letter above]](/sites/bibleinterp.arizona.edu/files/content/images/bro%20of%20jes.jpg)

of Yeshua [left side letter above] has both upper lines pointing in the same direction, diagonally to the left. Where the right side line turns into its lower extension, it does so with a curve rather than an oblique corner. The connection of the left side line to the lower extension of the right line is not perpendicular, but occurs at an acute angle. While both ayins are attractively cut, they are clearly different in terms of style and shape. This should not occur in a stone cut inscription of only twenty letters, particularly where the first eleven letters were made so uniformly. Clearly, the two ayins were not made by the same person. Again, the evidence points to a second hand at work, adding the phrase "brother of Jesus" to the original name of Yakov bar Yosef.

This is not to say that the Aramaic letters of the "brother of Jesus" are not shaped in ways we should expect from the first century C.E., when Jesus lived. On the contrary, the shape of the het is generally correct, and both the shin and the ayin are particularly well formed, and correspond to general trends known from the period of Jesus. This may be what accounts, in part, for the acceptance which the entire twenty letter inscription has found in some scholarly circles. Among known authentic inscriptions from the first century there are variations in the way nearly all Aramaic letters were formed. In fact, the Dead Sea Scrolls demonstrate that a single scribe might indeed form his letters in somewhat different ways upon a parchment or papyrus document of some length. But it is important to remember that we are dealing with a short inscription of only twenty letters engraved into stone, not a lengthy document written with pen and ink. The question is not whether some of the letters of the phrase "brother of Jesus" look correctly shaped for the first century period. The question is were they were engraved by the same person who engraved Yakov bar Yosef. It is to be expected that a five word inscription engraved into a stone ossuary would feature letter shapes of the last two words that looked the same as letter shapes of the first three words. But in the case of the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary this did not happen, because the final two words were added later, by different hands.

The most problematic feature of the "brother of Jesus" addition, in my opinion, is the letter identified by Andre Lemaire as a dalet. It is the fifth letter from the left in the added on portion of the inscription. Under normal circumstances we could expect a Jewish Aramaic inscription from the first century C.E. to feature the letter dalet in a form similar to the letters bet and resh. As can be seen in the figure below, which features the bet of Yakov [far right] and the resh of the word bar [second from right] as they appear in the inscription, these letters should be expected to feature a vertical line on their right hand side, and a horizonal line running leftward from the top of the vertical line and ending in a slightly upraised serif. If the ancient hand that made the bets and resh of Yakov bar Yosef also carved a dalet, then we ought to expect it to look like the model dalet below [second from left] which is based on features of the resh and the bets of Yakov bar Yosef. Its right side line would be nearly perfectly vertical, and its top line nearly perfectly horizontal, with slight extensions where the lines meet at the upper right and an upward serif at the left end of the top line.

![this is not the case with the alleged dalet of the inscription [above figure, far left]](/sites/bibleinterp.arizona.edu/files/content/images/ip3.png)

But this is not the case with the alleged dalet of the inscription [above figure, far left]. The only somewhat vertical line slants upward toward the right, and the not nearly horizontal line at the top slants diagonally upward to the left and lacks any serif. It also fails to extend on the right beyond the not-so-vertical line, but instead meets that line at an acute angle well below its top point. The letter is entirely uncharacteristic of the work done in the name Yakov bar Yosef, and cannot reasonably be assumed to have been engraved by the same hand that carefully carved those first eleven letters. In fact, this crudely formed "dalet" doesn't even appear as neatly done as the letters of Yeshua, three of which are also clearly different from those of Yakov bar Yosef. Something is definitely wrong here. Obviously, more than one hand was at work in this inscription, which is a strong indication that the "brother of Jesus" was added later — a strong indication of forgery.

What about the patina?

At this point, readers may rightly ask themselves "But what about the patina?" A letter from the Israeli Ministry of National Infrastructures Geological Survey, addressed to Biblical Archaeology Review editor Hershel Shanks and published with Lemaire's article of November 2002, certified that the surface of the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary featured a patina of grey to beige color.8

In addition to "What about the patina?" however, three other good questions to ask might be "What, actually, is patina?" and "Where, exactly, was the patina?" and most notably "Where wasn't there patina?"

In archaeological terms, the word "patina" is used to describe various types of thin film or coating which accumulate on artifacts over time. Patina is caused by a variety of chemical reactions involving the material of which an artifact was made, the environment in which it was deposited, exposure to direct moisture or humidity in the air, and the various soil types of the Land of Israel. But there are different patinas. For example, an ossuary which sat for centuries in a cave near Jerusalem, exposed to dust from the region's red, iron and calcium rich soil, but moistened only by the humidity of cave air, would develop patina different from that of a glass vessel buried in the sands of the coastal plain or a ceramic lamp buried in the volcanic soils of a tel near Lake Kinneret (the Sea of Galilee). Some patinas begin forming on artifacts very soon after they are deposited in a stationary situation. Some patinas are also easily removed by chemical treatment, washing, or scraping.

The Israeli Geological Survey analysis of the patina and a small amount of soil attached to the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary suggested that the limestone box had been left in a cave environment in the Mount Scopus or Mount of Olives area.9 This is entirely to be expected, since the ossuary is an authentic first century artifact, and was likely found in a burial cave in the Jerusalem area. The Geological Survey reported that grey patina was also found within some of the letters, although specific letters were not identified. Notably, patina was not found in several of the letters, which the Geological Survey attributed to the inscription having been cleaned. The Geological Survey also found no signs of use of a modern tool or other instrument. But the Geological Survey's letter did not detail where they did not find patina, and this is the most telling evidence of all.

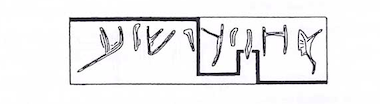

The Discovery Channel's television special "James, Brother of Jesus" revealed that patina was only obtained from the engraved lines of the letter sameh10 [inside the square in the figure below]. No patina is reported to have been found inside any of the nine letters of the "brother of Jesus" addition. Additionally, it is evident from photos of the ossuary published in Biblical Archaeology Review, but even more evident when one inspects the ossuary up close and personal (as thousands did when the artifact was displayed at the Royal Ontario Museum), that the area around the "brother of Jesus" portion of the inscription is completely without any of the beige to grey patina mentioned above, whereas the stone surface around the "Yakov bar Yosef" portion of the inscription is well coated with the reported patina. The irregular line in the figure below indicates the limits of the existing patina around the inscription. Left of the line (around the "brother of Jesus" addition) there is no patina on the ossuary surface! The only exception is the alef of "brother," which appears to cut through

surface patina. In general, in the area around the inscription, patina is found only on the right hand part of the surface, directly above, below, and over the Yakov bar Yosef part of the inscription. (Excellent color photos clearly showing the patina line on the ossuary were printed in the Biblical Archaeology Review of January 2003, including the photo on the magazine front cover.) Why is the left hand part of the surface around the inscription, including eight of the nine letters of the "brother of Jesus" portion of the inscription, void of patina? Probably because of modern forgers' efforts to erase the signs of their modern tool usage.

For anyone who might examine the ossuary inscription with a magnifier, the new cuts of the "brother of Jesus," which were probably made with a small steel nail, would be a dead giveaway that the work was a recent fake. Attempting to sand or buff such cuts would also be detectable under magnification. But for even modestly sophisticated antiquities forgers, undetectable smoothing of edges is not difficult. With soft limestone material, such as an ossuary, one of the most effective methods is to treat the engravings with a water stream using a garden hose and a small, high pressure nozzle. Forcing a small but strong water stream on the letters of the inscription for several minutes each day over a two to three week period will smooth sharp edges in a way that leaves no marks behind. But such high pressure water treatment will also soften, dissolve, and even cleanly remove any patina which may have built up on the limestone surface. This is apparently what happened with the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary.

The forgers covered the original letters of Yakov bar Yosef so that they would not be adversely affected, leaving only the letters of the newly carved "brother of Jesus" (except for the alef) exposed to the water jets. This may be why the Geologic Survey did not find any evidence of modern tool work, but it is also why there is no patina found around the left hand part of the inscription. It is also probably why the Geological Survey observed that the inscription had been "cleaned." The prolonged water jets also removed any minute metal shavings that could have been left behind by the nail or whatever other sharp tool the forgers had used. The result was a clean addition to the inscription, void of modern looking edges, but also void of surrounding patina, or any patina in the engravings. But this is not to say that all evidence of patina is gone. The limestone around the "brother of Jesus" is indeed stained a light beige color, due to the patina that used to be there. The patina itself, however, is gone, and the grooves of the lettering are not stained at all, because there was never any patina in them.

From close examination, though, it appears to me that the forgers made a mistake in their smoothing efforts. While covering the letters of Yakov bar Yosef prior to the beginning of their water treatment, they also inadvertently covered the first letter of the phrase they had added — the alef of the word "brother." The patina, through which the latter-day alef was carved, appears to remain just around the letter itself. This is an item which investigators at the Israeli Antiquities Authority may go back and check, because, to the naked eye at least, both the upper right and lower right extensions of that alef appear not only to have been cut through the patina, but to have retained rather sharp edges, probably from not having been water smoothed. If verified, this would be actual forensic evidence of modern forgery.

A summary note about the patina: Hershel Shanks has made an issue of proving that no patina was added to the ossuary surface. This is in response to some early claims that modern chemical treatment could be applied to the inscription to make it appear as if ancient patina were present. But spectrographic examination of the inscription by the Royal Ontario Museum confirmed that no modern chemical treatment had been applied.11 My point, however, has nothing to do with adding patina. I agree with Shanks that modern patina cannot be made and applied in a way that can escape detection. My point is much different — it is about the patina that isn't there.

The problem with "ahui"

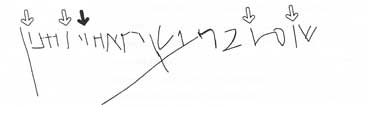

It seems to me that there is a significant problem with the suggestion that the word identified as "ahui" was used in the first century as a construct term for "brother." In a sidebar to Lemaire's article in Biblical Archaeology Review, editor Hershel Shanks reported that noted scholar Joseph Fitzmeyer had found two instances of this peculiar Aramaic "ahui" spelling from about the time of Jesus — one in the Genesis Apocryphon of the Dead Sea Scrolls and one on an ossuary inscription.12 The ossuary was subsequently identified in Shanks' book The Brother of Jesus as number 570 in Rahmani's Catalogue of Jewish Ossuaries.13 A photo of the ossuary appears in the book, as well as a drawing of the Aramaic inscription on its lid [the drawing is reproduced below]. This ossuary inscription is suggested by Fitzmeyer and Shanks as a parallel to the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary inscription in relation to the alleged appearance of the term "ahui." The inscription supposedly reads Shimi bar Asiya ahui Hanin or "Shimi son of Asiya brother of Hanin." But this "ahui" reading must also be challenged on epigraphic grounds. The letter suggested as a vav in the inscription [marked by a solid arrow below] should probably be read as a yod. Three other yods in the inscription, and probably a fourth yod that is the first letter of the final name, are all carved exceptionally long [they are marked by hollow arrows above]. The supposed vav of "ahui" is actually a perfect match for those four other yods. Rather than a reading of

ahui Hanin, with an unidentified long letter preceding Hanin, the last two words of the inscription should probably be read as ahi Yohanin or "brother of Yohanin." The short diagonal mark between the two long letters should not be read as a yod, since it is so dissimilar to all the other yods of the inscription — it was either a carving slip or a divider separating the yod of ahi from the yod of Yohanin. And if that little mark is not a yod, then the word "ahui" does not exist in the inscription. It cannot be used as a parallel to the alleged appearance of "ahui" on the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary.

How then, do we deal with "ahui" on the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary? My approach to this problem was briefly mentioned by Shanks in his book The Brother of Jesus, but not fully explained.14 So I will explain it here. I believe there may actually have been two forgers who created the "brother of Jesus" addition — one who was not very experienced with Hebrew and Aramaic lettering, and a second who was. It was the second forger that carved the name Yeshua in letters that were fairly handsome, albeit clearly different from those of Yakov bar Yosef. The first forger, whose hand scratched the four letters which Lemaire identified as "ahui", was not as talented as the one who followed, nor was he as careful as he needed to be. This is clear from an examination of the letter which has been identified as dalet.

If the other letters of the inscription, both the originals of Yakov bar Yosef and the well shaped addition of Yeshua, had been crudely and crookedly carved, we might be justified in guessing that we also had a crudely, crookedly carved dalet preceding Yeshua. But the other letters, both originals and additions, are well shaped and neat, if indeed different in the way described previously. So what do we make of this single, very sloppily made dalet? I suggest that it was not originally meant to be a dalet at all. I suggest that it started out to be a shin!

The person who started the process of forging "brother of Jesus" very likely had a drawing of what it was thought the words of that phrase should look like [see example below]. It probably read ahi Yeshua ("brother of Jesus"), employing the construct form of "brother" found in the Hebrew Bible. But it did not employ an Aramaic dalet preposition. No vav would have appeared in the word ahi. The drawing was probably not the work of the forger. It may have been made by someone the forger did not even know, but was obtained through extended contacts. The first forger probably did not even know the difference between ancient Aramaic and Hebrew.

The first forger sized up the existing, ancient Yakov bar Yosef inscription. Then, using a small steel nail, he began adding the desired addition. He scratched the three Aramaic letters alef, het, and yod, forming the word ahi or "brother of," doing a sloppy job on the alef, and then began work on the name Yeshua. He formed a second yod, and the first two lines of the shin, at which point he, or a partner looking over his shoulder, realized that a disaster was occurring. He was carving the shin backward! [The dotted line suggests how the shin would have been finished.]

Such a dyslexic mishap should not be considered unlikely or even unusual, since the first forger was probably not a native Hebrew speaker. His experience with Hebrew/Aramaic letters was probably to occasionally read them, but rarely to write them. One can almost hear the exasperated forger, and any partners he may have had, looking disgustedly at the backward half-shin carved into the purloined ossuary and exclaiming "What do we do now?"

What they did with the ossuary itself is not yet clear. Did they just give up and sell it to another party for whatever they could get? (This would be my best guess.) If they sold it, did they reveal to the buyer that they had added five letters onto the original inscription, enabling the buyer to attempt completion of the forgery? (See postscript below.) Or did they seek advice on how they might proceed themselves; perhaps even widening their circle of perpetrators to include a person with enough knowledge of Hebrew and Aramaic to attempt a fix of the situation the first forger had created? We may eventually find out what path the ossuary took prior to its public unveiling.

As for the inscription itself, however, it is clear from observation alone what happened. The course taken was to lengthen the yod of ahi into a vav, a fairly easy alteration which would eliminate the unseparated double yod the first forger had created. (An unseparated double yod would have been a giveaway that the addition was a fake.) The small curved stroke which lengthened the yod into a rather crooked vav is still quite visible [third letter from right in figure below]. It was probably hoped that the odd new "ahui" combination which resulted would be judged as an ancient blunder, or better yet, read as a defective Aramaic spelling. (See postscript below.) As for the backward half-shin, the second forger's course was to enhance the long line (by scratching it deeper), thus widening it ever so slightly, but to otherwise leave it alone [fifth letter from right in figure below]. Perhaps they reasoned it would be read as an eccentrically carved dalet acting as an Aramaic preposition, or at least be judged as the error of an ancient inscriber and disregarded.

That the person who finished the forgery was probably not the same person who made the first attempt at the job is evident from close examination of the nine letters of their work [see figure above, where first forger's work appears at right and second forger's work appears at left]. The inept hand that sloppily carved the alef [letter at far right] and then made the backward shin mistake seems to have been taken off the job. The second forger had a steadier hand and a better method of Hebrew/Aramaic lettering. The quality of letter formation is clearly more polished in the four forged letters of Yeshua [left, above] than in the poorly scratched letters that precede them. The shin of Yeshua is particularly well formed [third letter from left], and the yod and ayin of Yeshua are impressively executed, even though they are clearly different from the yods and ayin of Yakov bar Yosef. After water procedures to smooth sharp lines so that the additional words of the inscription appear older than they really are, the forgery was complete, and ready for public view.

But couldn't the "brother of Jesus" addition be ancient?

Even though it is obvious to the naked eye that the "brother of Jesus" portion of the inscription on the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary was added by different hands using a different tool than the hand and tool that engraved the name of Yakov bar Yosef, a legitimate question one might ask is: "Could this addition be ancient carving rather than a modern forgery?" To explore this issue it is necessary to review a bit of ancient Jewish history.

From the time of the death of James "the Lord's brother" in 62 C.E., Jews continued to live in Jerusalem and the vicinity round about until the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132-135 C.E.), a period of some seventy years. (The only interruption in that period, in the case of Jerusalem, was between 70 and 73 C.E., incident to the end of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome.) If, a year or so after his death and burial, James' bones were in fact deposited in an ossuary sometime around 63 or 64 C.E., and his name and the name of his father were carved into the ossuary at that time, it may not have been until after 73 C.E. that someone might have felt the need to further identify the owner of those bones as having belonged to the "brother of Jesus." This would leave just over six decades (from 73 to 135 C.E.) for the addition to have taken place.

Following the Second Jewish Revolt, Jews were banished from Jerusalem and Judea by decree of the Roman emperor Hadrian, who at the same time changed the name of the province to Palestine in order to disassociate the Jewish people from its homeland. This also marked the end of Jerusalem's community of believers in Jesus, who were virtually all Jews, and who were the only people at that time who might have been interested in the identity of James. After the Second Revolt there was no one in the vicinity of Jerusalem who would have thought any ossuary inscription mentioning James might need an additional phrase. Is it possible, then, that in those six decades one or more Jewish believers in Jesus entered a tomb containing James' ossuary and noticed that it bore only his name and that of his putative father, and then decided to add nine more letters that would also identify him as the "brother of Jesus" for those future generations who would somehow chance into the burial cave and decide to inspect the ossuary? Possible? Well, yes, anything is possible. But likely? In the case of the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary, not very.

If the nine letters of the "brother of Jesus" on the ossuary were an ancient addition, the following questions would have to be plausibly answered: First, why is the construct spelling of "brother" so odd? Normally it would be spelled ahi, the same in Aramaic as in Hebrew. Although Joseph Fitzmeyer identified two other first century instances of the peculiar "ahui" spelling, if my suggestion about the Shimi bar Asiya inscription is correct then the single appearance of "ahui" in the Genesis Apocryphon must be regarded as a defective spelling — a misspelling. The question is, if the "brother of Jesus" phrase was an ancient addition made by an Aramaic speaking Jew, why couldn't the carver spell the word "brother" correctly?

The second question is why the dalet was so poorly executed. If it is postulated that an ancient Jew wished to add the phrase "brother of Jesus" to a name on an ossuary, the use of the letter dalet as an Aramaic preposition of possession or relation would not be unexpected. But it is also to be expected that the same Jew who successfully carved a reasonably handsome Yeshua could somehow have managed to carve a decent looking dalet. The letter is so poorly formed, however, that it is almost unrecognizable as a dalet. Why couldn't the carver execute a respectable looking dalet? And for that matter, why couldn't he carve a respectable looking alef?

The third question is why no patina appears around the "brother of Jesus" addition. Since the only time in antiquity that this addition could plausibly have been added was between the years 73 and 135 C.E., the same patina that developed around the words Yakov bar Yosef should surely have developed around the "brother of Jesus" during 1,900 years in a burial cave setting. It is to be expected that, if the addition were an ancient one, patina would have developed upon the entire face of the inscription, not just on the end around the words Yakov bar Yosef. We should expect, even today, to see the same greyish-beige patina surrounding the words "brother of Jesus," and also within the engraved letters themselves, as we see around and in the letters of Yakov bar Yosef. Yet we do not. Why isn't there any patina in and around the "brother of Jesus?"

The answer to all these questions is that the "brother of Jesus" addition is far more likely the work of modern forgers than the effort of ancient hands. Any one of these three issues alone might not be enough to disqualify the suggestion of ancient origin for the addition, but all three together present a formidable body of suggestive evidence against the idea that the "brother of Jesus" was added to the ossuary inscription by an ancient Jew in Jerusalem.

A final observation

As a postscript to this report I mention something I noticed in the Forward to Hershel Shanks' book The Brother of Jesus. The Forward was written by Andre Lemaire. On its first page, Lemaire writes about meeting the ossuary's present "owner," who is not named in the book, but whose identity we now know. Lemaire reports that on the day he saw a photo of the inscription for the first time, "the owner said he thought the inscription was especially interesting because there was only one other inscription in Rahmani's Catalogue (the standard catalog of Jewish ossuaries) mentioning a brother in a similar way."15 This statement can only refer to the "ahui Hanin" reading from ossuary 570 of Rahmani's Catalogue. But this is quite astounding.

It means that "the owner" knew of the "ahui Hanin" reading from Rahmani's ossuary 570 long before he ever met Lemaire, and long before Joseph Fitzmyer identified that same "ahui Hanin" reading as a parallel to the "ahui d'Yeshua" phrase on the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary. Recall that months after Lemaire met "the owner," Biblical Archaeology Review editor Hershel Shanks had sought Fitzmyer's opinion on the "brother of Jesus" inscription before he went to press with it. Shanks reported that "Fitzmyer was troubled by the spelling in the James inscription of the word for 'brother'" but that "after doing some research ... he found another example in which the same form appeared — in an ossuary inscription in which the deceased was identified as someone's brother."16 Fitzmyer had found ossuary 570 in Rahmani's Catalogue. Fitzmyer's finding is portrayed by Shanks as the ultimate breakthrough, the evidence which certifies the inscription's authenticity.

His conclusion was that "either the forger of this inscription knows Aramaic better than Joe Fitzmyer, or it is authentic!"17 However, a very different conclusion could also be reached: that someone else had noticed the "ahui Hanin" reading of ossuary 570 long before Lemaire or Fitzmyer came into the picture, and had used it to fix a previously botched forgery job by correcting it to read "ahui d" before adding the name Yeshua. The forger knew that at least some scholars would eventually authenticate the "brother of Jesus" forgery, because they would find (or could be guided to) the "ahui" reading of ossuary 570. Since we know that "the owner" advised Lemaire concerning that reading even before showing him the "brother of Jesus" inscription, we have to wonder if he played any roll in the inscription's creation. In any event, the creation of the "brother of Jesus" inscription certainly bears further investigation.

Jeffrey R. Chadwick is associate professor of Church History at Brigham Young University, Utah, U.S.A., where he teaches courses in Judaism and New Testament, and visiting professor of Near Eastern Studies at the Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem, Israel, where he teaches archaeology and historical geography. He holds a Ph.D. in archaeology and is a practicing field archaeologist at sites in Israel.

ENDNOTES

[1] Andre Lemaire, "Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus." Biblical Archaeology Review Vol. 28 No. 6 (November/December, 2002), 24-33.

[2] "James, Brother of Jesus," cable television special on the Discovery Channel, first broadcast 20 April 2003. Discovery Communications, Inc., 2003.

[3] Hershel Shanks and BenWitherington III, The Brother of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco, 2003.

[4] For this article it was necessary for the author to create a new and original drawing of the twenty letter inscription on the Yakov bar Yosef ossuary. The drawing by Ada Yardeni which appeared in Biblical Archaeology Review of November/December 2002 (pages 26-27) was incorrect in some aspects and failed to represent certain important details of the inscription.

[5] James is not specifically called the "brother of Jesus" in the New Testament, but the apostle Paul referred to him as "the Lord's brother" in Galatians 1:19, and Matthew 13:55 mentions James as one of the "brethren" of Jesus.

[6] Etgar Lefkovits, "Antiquities Authority to investigate mystery 'King Joash' tablet." Jerusalem Post, internet edition (www.jpost.com) 17 March 2003.

[7] Lemaire, "Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus," 28.

[8] Lemaire, "Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus," 29.

[9] Lemaire, "Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus," 29.

[10] As reported in "James, Brother of Jesus," Discovery Communications, Inc., 2003.

[11] As reported in "James, Brother of Jesus," Discovery Comminucations, Inc., 2003.

[12] Shanks, "The Ultimate Test of Authenticity." Biblical Archaeology Review Vol. 28 No. 6 (November/December, 2002), 33.

[13] Shanks, The Brother of Jesus, 17 and 22 note #1. See also L. Y. Rahmani, A Catalogue of Jewish Ossuaries in the Collections of the State of Israel. Jerusalem:Israel Antiquities Authority / Israel Academy of Sciences and Humaninites, 1994, no. 570.

[14] Shanks, The Brother of Jesus, 43.

[15] Shanks, The Brother of Jesus, xi (Forward by Andre Lemaire).

[16] Shanks, "The Ulitimate Test of Authenticity," 33.

[17] Shanks, The Brother of Jesus, 16.