The law code of the book of Deuteronomy is capped with a series of curses that threaten harm upon any individual that should fail to keep the Deuteronomic laws. While this method of divine encouragement to keep the commandments of God might seem surprising from a theological point of view, curses were an integral part of the legal, political and religious life of the ancient Near East, found in a variety of ancient texts including the Hebrew Bible, Neo-Assyrian treaties, and Northwest Semitic inscriptions. Placing the biblical curses within the larger context of this ancient Near Eastern material provides new insights into the background and function of the curses in the book of Deuteronomy.

See Also: Deuteronomy 28 and the Aramaic Curse Tradition (Oxford Theology and Religion Monographs; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

By Laura Quick

Assistant Professor of Religion and Judaic Studies

Princeton University

March 2018

In the Hebrew Bible, you really are “damned if you don’t.” The law code of the book of Deuteronomy is capped with a series of curses that threaten harm upon any individual that should fail to keep the Deuteronomic laws. While this method of divine encouragement to keep the commandments of God might seem surprising from a theological point of view, curses were an integral part of the legal, political and religious life of the ancient Near East, found in a variety of ancient texts including the Hebrew Bible, Neo-Assyrian treaties and Northwest Semitic inscriptions. Placing the biblical curses within the larger context of this ancient Near Eastern material provides new insights into the background and function of the curses in the book of Deuteronomy, and in the Hebrew Bible more generally.

It has become fairly common in the history of the interpretation of the book of Deuteronomy to understand the book as a covenant or treaty detailing the terms of the relationship between God and man, and developed along the same structural lines as ancient Near Eastern treaty texts. Both Deuteronomy and ancient Near Eastern treaty texts feature a similar structure with a historical prologue before a section of legal material and finally blessings and curses. In particular, a Neo-Assyrian treaty written in Akkadian in the seventh century BCE, “The Succession Treaties of Esarhaddon” (“EST” for short) has been suggested by some scholars to provide direct parallels with some of the curses found in Deuteronomy 28 (Weinfeld 1965; Frankena 1965; Levinson and Stackert 2012). Esarhaddon was the third king of the Sargonid Dynasty of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and the Succession Treaties are the formal record of a treaty concerning the royal succession of Esarhaddon’s chosen heir, his son Assurbanipal, in Assyria, written in 672 BCE. On the other hand, a number of scholars have been wary to posit a direct literary relationship between the Succession Treaties and the book of Deuteronomy, usually due to their reticence to attribute the kind of Akkadian literacy that this would necessitate to the Hebrew scribes who wrote the biblical text (e.g., Morrow 2005; Crouch 2014). The past few decades have brought to light additional inscriptions that also provide paralleled phenomena to the curses in Deuteronomy 28. Unlike the Esarhaddon Treaty, these inscriptions are written in Old Aramaic, a Northwest Semitic language utilized in Syria during the first millennium BCE. Thus these inscriptions are both geographically and linguistically closer to the biblical world than the Mesopotamian texts which scholars have previously referred to Deuteronomy 28.

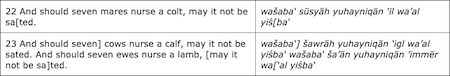

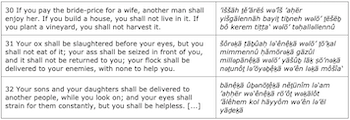

The particular curse form common to the Old Aramaic inscriptions and Deuteronomy 28 can be described as curses of futility, with a characteristic syntactical form and commonalities in both vocabulary and ideation. These curses all provide a protasis that defines an action of some kind, followed by an apodosis in which this action is frustrated: we might typify this curse as a threat of maximum effort, but minimal gain. Several characteristic examples can be found in the Sefire treaties, three treaties written in Old Aramaic and discovered near present day Aleppo. The inscriptions are the first and only treaties that have been found in Aramaic, a Northwest Semitic language closely related to Hebrew (for the text see Donner and Röllig 2002; vocalization and translation is my own).

Sefire Treaties (KAI 222 A1:22-23)

Many biblical texts and Old Aramaic inscriptions partake in this literary form, with a total of forty-three discrete examples of the futility curse across all biblical books, especially in Deuteronomy 28 and in pre-exilic prophetic texts: Lev. 26:26; Deut. 28:30 (x3), 31 (x3), 38, 39, 40, 41; Isa. 5:10 (x2); Jer. 11:11; Hos. 2:9 (x2); 4:10 (x2); 5:6; 8:7; 9:12, 16; Amos 4:8; 5:11 (x2); 8:12; Micah 3:4; 6:14 (x2), 15 (x3); Zeph. 1:13 (x2); Hag. 1:6 (x4); Zech. 7:13; Mal. 1:4; Ps. 127:1; Job 31:8; and Prov. 1:28 (x2). Meanwhile, across the corpus of Old Aramaic inscriptions, there are nineteen occurrences of the futility curse, stemming from three separate inscriptions datable within the range of the ninth to the eighth centuries BCE, and with a geographic distribution across the Trans- and Cisjordan: from the Tell Fakhariyah bilingual inscription (x6); the Sefire treaties (x11); and the recently discovered stele from Bukān (x2). The syntactical, lexical and ideational regularity of the futility curses demonstrates that it was a standard literary form which was utilized by Northwest Semitic scribes in the first-millennium BCE (see also Ramos 2016). This is important for understanding the book of Deuteronomy, showing that Deuteronomy 28 cannot be understood according to Mesopotamian conceptions alone, despite the previous scholarly ferment in that direction. Rather, Deuteronomy 28 mediates between the traditions of the East and West, featuring characteristic examples of the Northwest Semitic futility curse type, as well as curses more common to Akkadian, East Semitic texts like the Esarhaddon Treaties.

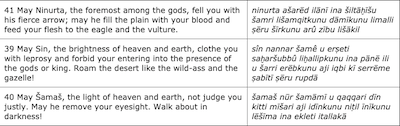

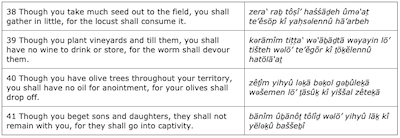

The traditional formulation of the Deuteronomy // Esarhaddon Treaties hypothesis is concerned with Deuteronomy 28:26-35 in comparison with EST §§ 39-42 (for the text, see Parpola and Watanabe 1987; vocalization and translation is my own).

EST §§ 39-41

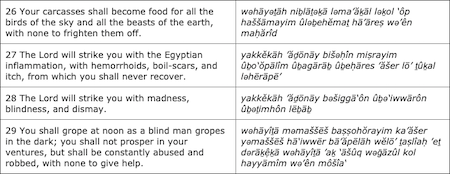

This has parallels with Deuteronomy 28:26-29:

Deut. 28:26-29

It appears that the text of the Esarhaddon Treaties provides correspondences with these verses from Deuteronomy, with both texts reflecting curses threatening the attack of carrion, skin disease and blindness, the latter including the terminological overlap of movement “in the dark” (albeit Deuteronomy 28:26 occurs out of sequence). Indeed, the text in Deuteronomy seems to build upon and amplify the Akkadian, adding additional clauses that stress the perpetuity of the curse, so “you shall never recover... with none to give help...”

Yet immediately following Deut. 28:26-29, we find curses that seem to cohere more with the tradition of the futility curse, the curse of maximum effort but minimal gain, which I have proposed was traditional to Northwest Semitic literary compositions. At the same time, the Esarhaddon Treaties still provide the conceptual framework for these curses.

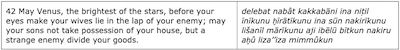

EST §42

Deut. 28:30-32

Here Deuteronomy develops the idea world of the parallel curse in the Esarhaddon Treaties – so unfaithful wives and houses in which the owner cannot reside – but couches these motifs in the characteristic syntactic form of the futility curse, significantly expanding upon the Akkadian original by adding further clauses that develop traditional Northwest Semitic motifs concerning frustrated vineyards and livestock (see Smoak 2008). Then the text returns in v. 32 to more faithfully reflect the Akkadian, abandoning the syntax of the futility curse and stressing along with the Esarhaddon Treaties that the root cause of the curse – which in both seems to envision deportation – will be at the hand of an enemy nation, so in Hebrew “another people” and in the Akkadian a “strange enemy.”

Immediately following this statement, the text shifts again, employing further curses in the guise of the futility form.

Deut. 28:38-41

The motifs in this section of text are characteristic of the scriptural and inscriptional Northwest Semitic texts found in Old Aramaic and in the Hebrew Bible, utilizing a similar repertoire of language and stock images of vineyards and olive groves, all couched in the syntax of a maximum effort but a minimal gain. Once again, in this portion of Deuteronomy 28, the orientation of the text has shifted back to Northwest Semitic ideas and metaphors. Deuteronomy marries curses from the East Semitic world with native Northwest Semitic traditions, opposing the traditions against each other in a playful exchange (Quick 2017).

How did these parallels come into existence? In the case of traditions of cursing and treaties, ritual performance could provide a useful perspective with which to think through the connections between these traditions. Both the biblical and inscriptional texts seem to demonstrate a large body of rites and rituals that would have come along with the formalization of a treaty or covenant. Very often some sort of sign must mark the spot of the treaty agreement. This seems to have been essential to both cosmic and terrestrial covenants. The rainbow in the Noaic covenant in Genesis 6, or the tablets of stone in the Mosaic covenant in Exodus 24, can be understood in this way. In Deuteronomy, this is taken further still, thus “Impress these My words upon the doorposts of your house and on your gates” (Deut. 11:18-20; cf. Deut. 6:9-8). In Joshua 24, a large stone acts as witness to “all the words that the Lord spoke to us.” A standing stone is also utilized in the ratification of the covenant between two human actors, so Jacob and Laban in Genesis 31; while it is a tamarisk tree that marks the spot of the agreement between Abraham and Abimelech in Genesis 21. A sacrifice or ritual slaughter seems to have been inherent to many of the biblical covenants. Indeed, that the cutting up of an animal in sacrifice also informed the biblical terminology “to cut” a covenant – rather than to “establish” or “set up” – has been suggested (Day 2003). In particular, note the Abrahamic covenant of Genesis 15:

7 Then he said to him, “I am the Lord who brought you out from Ur of the Kaldeans to assign this land to you as a possession.” 8 And he said, “O Lord God, how shall I know that I am to possess it?” 9 He answered, “Bring Me a three-year-old heifer, a three-year-old she-goat, a three-year-old ram, a turtledove, and a young bird.” 9 He answered, “Bring Me a three-year-old heifer, a three-year-old she-goat, a three-year-old ram, a turtledove, and a young bird.” 10 He brought Him all these and cut them in two, placing each half opposite the other; but he did not cut up the bird. 11 Birds of prey came down upon the carcasses, and Abram drove them away. [...] 17 When the sun set and it was very dark, there appeared a smoking oven, and a flaming torch which passed between those pieces. 18 On that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram.

Here animals are cut in two, before a flaming torch passes between the two parts of the animals in a symbolic procession. A comparable situation is found in Jeremiah 34:

18 I will make the men who violated My covenant, who did not fulfill the terms of the covenant which they made before Me, like the calf which they cut in two so as to pass between the halves: 19 The officers of Judah and Jerusalem, the officials, the priests, and all the people of the land who passed between the halves of the calf. 20 shall be handed over to their enemies, to those who seek to kill them. Their carcasses shall become food for the birds of the sky and the beasts of the earth.

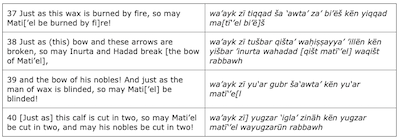

Here God chastises the men who violated his covenant, recalling when they had passed between the two halves of a sacrificed calf, and threatening that he will make these men like that calf. The logic of this passage seems to recall the simile curses found in the Neo-Assyrian and Aramaic treaty texts:

Sefire Treaties (KAI 222 A1:37-40)

Just as certain items are broken, cut or burnt, so will the treaty partner be broken, cut or burnt, should he not keep the terms of the agreement. These curses are not just speech acts: the text is explicit that an accompanying rite is meant to posit the association between the broken object and the cursed individual.

Clearly the ritual context of treaty formation in ancient Israel and Judah involved a complex body of rites and actions, encompassing at the very least signs, sacrifice, the recitation and writing of curses and perhaps a ritual procession between the two halves of an animal as implied in Genesis 15, and explicit in Jeremiah 34. If the ritual aspect of these treaty texts is emphasized, then the need for a formal written translation of the Esarhaddon Treaties may very well be negated. Just as Ezra had intermediaries to help the people “understand the reading” of the Torah, “translating it and giving the sense” (Neh. 8:7), could this practice of Targum have also played a role in any aural ceremony? Certainly this is the logic that underlines the treaty formalized between Jacob and Laban, and the “mound of witness” that acts as the sign of their covenant, named in Aramaic by Laban, and in Hebrew by Jacob (Genesis 31:47). This may well account for the problem of Akkadian literacy in Judah. As the Israelites and Judaeans increasingly interacted with and were subjugated by the Neo-Assyrians, the ritual world of their treaty formulation opened up to include East Semitic practices and idioms – and these idioms, translated into Aramaic or Hebrew and shared orally in ritual performance, found their way into the written text of Deuteronomy 28. In this way, it could be said that the curses of Deuteronomy 28 parallel those of the Aramaic epigraphs and the Neo-Assyrian treaty texts due to the reality of the ritual world of the scribes, rather than because of any particular written tradition at their disposal.

Deuteronomy 28 cannot be understood apart from the Northwest Semitic tradition of the futility curse. As well as helping us to understand the compositional process that belies the book of Deuteronomy, this recognition increases our understanding of the ritual context of treaty formation in the ancient Near East. Indeed, ritual has a theoretical capacity to account for the transmission of these curse traditions cross-culturally. I also want to stress the importance of these Northwest Semitic inscriptions for understanding the production of biblical literature in general. Compositions in Old Aramaic, Phoenician, Moabite, Ammonite or Edomite, as well as in Epigraphic Hebrew, while much narrower in scope than the possibilities presented by the Mesopotamian material due to the limited nature of the documentary finds, nevertheless should be our first point of departure when discussing the writing culture of the ancient Levant. If we are to understand anything about the composition of the Hebrew Bible, especially in comparison with texts from the ancient Near East, we must first nuance our attempts with detailed consideration of the writing culture of the ancient Levant – incorporating oral and written modes of literary transmission, the Northwest Semitic literary remains, scribal practice, and bilingualism.

Reference List

Crouch, Carly L. 2014. Israel & the Assyrians: Deuteronomy, the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon, & the Nature of Subversion. ANEM, 8; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

Day, John. 2003. “Why Does God ‘Establish’ rather than ‘Cut’ Covenants in the Priestly Source?” pp. 91-106 in Covenant as Context: Essays in Honour of E.W. Nicholson, ed. Andrew D.H. Mayes and R.B. Salters. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Donner, Herbert and Wolfgang Röllig. 2002. Kanaanäische und aramäische Inschriften 1 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz).

Frankena, Rintje. 1965, “The Vassal-Treaties of Esarhaddon and the Dating of Deuteronomy,” Oudtestamentische Studiën 14: 122-154.

Levinson, Bernard M. and Jeffrey Stackert. 2012. “Between the Covenant Code and Esarhaddon’s Succession Treaty,” Journal of Ancient Judaism 3: 123-140.

Morrow, William S. 2005. “Cuneiform Literacy and Deuteronomic Composition,” Bibliotheca Orientalis 62: 204-213.

Parpola Simo and Kazuko Watanabe. 1988. Neo-Assyrian Treaties and Loyalty Oaths. SAA, II; Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

Quick, Laura. 2017. Deuteronomy 28 and the Aramaic Curse Tradition. Oxford Theology and Religion Monographs; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ramos, Melissa. 2016. “A Northwest Semitic Curse Formula: The Sefire Treaty and Deuteronomy 28,” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 128: 205-220.

Smoak, Jeremy D. 2008. “Building Houses and Planting Vineyards: The Inner-Biblical Discourse on an Ancient Israelite Wartime Curse,” Journal of Biblical Literature 127: 19-35.

Weinfeld, Moshe. 1965. “Traces of Assyrian Treaty Formulae in Deuteronomy,” Biblica 46: 417-427.

Comments (1)

Can’t avoid a pang of depression when it appears that my religion and that of so many others rests on a sacred book which gives an important places to, of all things, futility curses. How mysterious is the work of the Spirit!

#1 - Martin Hughes - 03/17/2018 - 11:32