As biblical scholars engage ancient Near Eastern iconography for the purpose of interpreting the biblical texts, one must be constantly aware that reading texts and seeing images are different process with their own distinct steps. It should not be surprising, therefore, that questions of method have dominated recent studies of the relationship of iconography and biblical texts.

See Also: Image, Text, Exegesis: Iconographic Interpretation and the Hebrew Bible (The Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, 2014)

By Izaak J. de Hulster

Sofja Kovalevskaja research group on Early Jewish Monotheism

Georg-August Universität in Göttingen, Germany

Joel M. LeMon

Assistant Professor of Old Testament

Emory University, Atlanta

Associate Professor Extraordinary

University of Stellenbosch, South Africa

September 2013

Most scholars of the Hebrew Bible share a common understanding: a text must be read in its historical context. However, scholars often do not agree about the relative value of different types of historical data. What sources of data could, should, and, in fact, must be considered for one’s work to qualify as a valid historical-critical exercise? Answers vary widely.

Scholars typically address this question implicitly through the methods they choose to employ when engaging a text. A survey of the dominant methods in the field suggests that many scholars turn first to ancient Near Eastern texts to establish the historical context of the Hebrew Bible. The Bible is, after all, an ancient Near Eastern text.

Yet increasingly, biblical scholars are also turning to non-textual sources of data from the ancient Near East, namely, pictorial material, or ancient Near Eastern iconography. This material can be as important as—or, in some cases, even more important than—ancient Near Eastern texts for understanding the historical context of the Hebrew Bible.

This claim might come as a surprise to some, given that the Hebrew Bible, at least in part, reflects an aniconic ideology. However one construes the image ban, that it appears at all betrays the fact that the world of the Hebrew Bible was a world shot through with images. And these images were powerful expressions of cultures that created them. For why else would images be banned?

As a discrete method of biblical interpretation, “the iconographic approach” interprets the Hebrew Bible in light of the iconographic background of the ancient Near East. The approach takes seriously the fact that the Hebrew Bible was composed within a world of images. Thus, to understand the fullest historical context from which a text emerged, one must engage images. Words and images together provide expressions of the cultures that produce them.

The iconographic approach has shown repeatedly that the biblical text manifests a distinct awareness of the power of images. For example, Silvia Schroer’s monumental volume In Israel gab es Bilder [There were Images in Israel] (1987) highlights numerous biblical texts that refer to images, situating these texts alongside the relevant archaeological evidence.

Lachish, c. 8th/7th cent. B.C.E. After Othmar

Keel's Jahwe-Visionen, Abb. 92, p. 109.

Another important example, Othmar Keel’s Jahwe-Visionen und Siegelkunst [Visions of Yahweh and (ANE) Seal-Art] (1977), famously shows how Isaiah 6 reflects an awareness of the power of images. Keel argues that Isaiah’s vision mocks his contemporaries’ use of apotropaic amulets that depicted four-winged cobras [fig. 1].

In the iconographic context of eighth century Judah, the four outstretched wings of the cobra were understood to provide ample protection for the owner of the amulet, whose name was often written below the image. Yet Isaiah’s vision presents a striking development and reversal of this imagery. It pictures six-winged fiery serpents—more wings signify more protection—which use their wings no to protect a person but to shield themselves from the image of God’s majesty.

Studies like this have revealed the complex interplay between text and image throughout the Hebrew Bible. In fact, some of the most important contributions of this type have come through studies of poetry and figurative language, especially metaphor. Indeed, Othmar Keel initiated the modern iconographic approach through just such a study on the Psalms with The Symbolism of the Biblical World (originally published in German in 1972).

Through this and many other iconographic works, scholars have shown that ancient Near Eastern images have their own syntax, forms, and ways of creating and conveying meaning. We should not view them as more-or-less photographic representations depicting the world as the human eye perceives it (Sehbild), but rather like picture- puzzles, providing elements that are to be considered together within constellations of images. Thinking through the connections among these elements is the way one makes sense of an image (Denkbild).

After http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/51/%22Pond_in_a_Garden%22_%28fresc

o _from_the_Tomb_of_Nebamun%29.jpg (7 August 2013).

Consider, for example, this image from the Tomb of Nebamum [fig. 2].

At first glance, the modern eye might perceive that the trees and plants are cut down and lying around the central pool. However, given the immediate pictorial context and with an understanding of the art historical context, namely, the Egyptian conventions for portraying pictorial elements from their most immediately recognizable perspective, one can understand this image as a stand of trees and shrubs surrounding a central fishpond.

After http://jfbradu.free.fr/egypte/LES%20TOMBEAUX/LES%20HYPOGEES/VALLEE

-DES-ROIS/RAMSES-VI/RAMSES-VI.php3?r1=5&r2=0&r3=0 (7 August 2013).

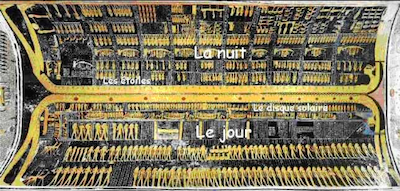

The artistic syntax for representing abstract concepts is even more complicated, requiring a thorough understanding of the constellation of images in the scene and the larger patters of representation within a particular culture and in a particular time. Consider the image from the ceiling of the tomb of Ramesses VI [fig. 3]. In a vast and complex scene, this image pictures the cosmos, with its double portrayal of the sky goddess Nut arching across the heavens.

The conventions of Egyptian art provide but one example of the necessity for modern observers to acquire different ways of seeing when they encounter images from the ancient Near Eastern. In other words, the study of ancient images requires an awareness of the essential nature of such images. Keel described the principle as “the right of images to be seen,” the title of his 1992 monograph, Das Recht der Bilder gesehen zu werden. Images are not to be read like texts but seen, treated as visual artifacts.

As biblical scholars engage ancient Near Eastern iconography for the purpose of interpreting the biblical texts, one must be constantly aware that reading texts and seeing images are different process with their own distinct steps. It should not be surprising, therefore, that questions of method have dominated recent studies of the relationship of iconography and biblical texts (see, especially, Izaak J. de Hulster Iconographic Exegesis and Third Isaiah [2009], Joel M. LeMon, Yahweh’s Winged Form in the Psalms [2010], and, for the New Testament, Annette Weissenrieder/ Friederike Wendt/ Petra von Gemünden (eds), Picturing the New Testament: Studies in ancient visual images, 2005).

In addition to this infusion of energy around methodological issues, scholars employing the iconographic approach have also benefited from the recent publication of multi-volume compendia of iconographical materials from the Levant. The two most outstanding projects are the volumes in Die Iconograpie Palästinas/Israels und der Alte Orient: Eine Religionsgeschichte in Bildern (IPIAO) under the direction of Silvia Schroer and Othmar Keel’s Corpus der Stempelsiegel-Amulette aus Palästina/Israel: Von den Anfangen bis zur Perserzeit. Thanks to these and other resources, biblical scholars now have more access to the ancient Near Eastern iconographic repertoire than ever before.

One indication of the growing awareness of the value of this pictorial material can be seen in the programming of the Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature. This year in Baltimore, the Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Bible program unit will host no less than five sessions. The first session will contain papers on the broad topic of the relationship between ANE iconography and the ancient Near East. Two more sessions will be devoted entirely to the study of Iron Age terracotta figurines from the Levant. Another session sponsored jointly with Metaphor Theory and Hebrew Bible program unit will focus on the topic “God, Metaphor, and Iconography.” And yet another session will be offered in conjunction with the Israelite Religion in its West Asian Environment program unit.

Attention to images in some form or another has in fact been a part of the landscape of biblical studies for some time. In 1927, Hugo Gressmann called for the analysis of images: “‘Texts’ and ‘images’, philology and archaeology, are equally indispensible for a historian. They necessarily belong together. They presuppose one another, complement one another, assay one another, and provide a mutual witness to one another” (viii, our translation). His exhortation rings particularly true today as the analysis of images occurs more frequently within biblical studies, and with ever-increasing levels of methodological clarity and sophistication.

Some helpful resources both on the web and in print:

- “Sources for the Use of Ancient Images in Biblical Studies (Old Testament)”

http://archeologiepalestina.blogspot.de/2010/07/sources-for-use-of-ancient-images-in.html - “Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East”

http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/ - “Bibel+Orient Datenbank Online”

http://www.bible-orient-museum.ch/bodo - “The Iconography of Palestine/Israel and the Ancient Near East”

http://www.ipiao.unibe.ch/en/intoduction.html - “European Association of Biblical Studies research group for ‘Iconography and Biblical Studies’”

http://www.eabs.net/site/research-groups/general/iconography-and-biblical-studies/ - “The Iconology Research Group of the University of Leuven and the University of Utrecht”

http://www.iconologyresearchgroup.org/

We list this site as an example because the interplay between biblical texts and pictorial images is also a primary concern for scholars exploring the reception of the text in biblical art. Indeed, a number of methodological affinities obtain between these otherwise diverse areas of biblical scholarship.

Bibliography

Akerman, J.Y., 1845-1846, Numismatic illustrations of the narrative portions of the New Testament, Numismatic Chronicle 8, 133-162 and idem, 1846-1847, Numismatic illustrations of the Acts of the Apostles, Numismatic Chronicle 9, 17-43 (Akerman’s articles are among the first employing ancient images for exegetical purposes)

Bätschmann, O., 62009, Einführung in die kunstgeschichtliche Hermeneutik: Die Auslegung von Bildern, Darmstadt

De Hulster, I.J., 2009, Iconographic Exegesis and Third Isaiah (FAT-II 36), Tübingen

De Hulster I.J. / Schmitt, R. (eds), 2009, Iconography and Biblical Studies [proceedings EABS/SBL conference Vienna 2007] (AOAT 361), Münster

De Hulster, I.J / LeMon, J.M. (eds), forthcoming, Image, Text, Exegesis: Iconographic Interpretation and the Hebrew Bible (LHBOTS), London

Gressmann, H., 21927, Altorientalische Bilder zum Alten Testament, Berlin

Keel, O., 1972, Die Welt der altorientalischen Bildsymbolik und das Alte Testament. Am Beispiel der Psalmen, Zürich (Göttingen, 5th ed., 1996; English translation: The Symbolism of the Biblical World. Winona Lake, Ind., 1997)

Keel, O., 1974, Wirkmächtige Siegeszeichen im Alten Testament. Ikonographische Studien zu Jos 8,28; Ex 17,8-13; 2Kön 13,14-19 und 1 Kön 22,11 (OBO 5), Fribourg

Keel, O. 1977, Jahwe-Visionen und Siegelkunst. Eine neue Deutung der Majestätsschilderungen in Jes 6, Ez 1 und 10 und Sach 3 (Stuttgarter Bibel-Studien 84/85), Stuttgart

Keel, O., 1978, Jahwes Entgegnung an Ijob. Eine Deutung von Ijob 38-41 vor dem Hintergrund der Zeitgenössischen Bildkunst (FRLANT 121), Göttingen

Keel, O., 1986, Das Hohelied (Zürcher Bibelkommentare. Altes Testament 18), Zürich (English translation: The Song of Songs: A Continental Commentary. Minneapolis, 1994)

Keel, O., 1992, Das Recht der Bilder gesehen zu werden. Drei Fallstudien zur Methode der Interpretation altorientalischer Bilder (OBO 122), Fribourg

Keel, O. / Uehlinger, C., 11992 / 62010, Göttinnen, Götter und Gottessymbole. Neue Erkenntnisse zur Religionsgeschichte Kanaans und Israels aufgrund bislang unerschlossener ikonographischer Quellen (Quaestiones disputatae 134), Freiburg in Breisgau (English translation: Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel; Minneapolis, 1998)

Klingbeil, M., 1999, Yahweh fighting from heaven: God as warrior and as God of heaven in the Hebrew Psalter and ancient Near Eastern iconography (OBO 169), Fribourg

LeMon, J.M., 2010, Yahweh’s winged form in the Psalms: Exploring congruent iconography and texts (OBO 242), Fribourg

Metzger, M., 1985, Königsthron und Gottesthron: Thronformen und Throndarstellungen in Ägypten und im Vorderen Orient im dritten und zweiten Jahrtausend vor Christus und deren Bedeutung für das Verständnis von Aussagen über den Thron im Alten Testament (AOAT 15/1+2), Kevelaer

Metzger, M., 2003, Vorderorientalische und Altes Testament: Gesammelte Aufsätze (Jerusalemer theologisches Forum 6), Münster

Nissinen, M. / Carter, C.E. (eds), 2009, Images and prophecy in the ancient eastern Mediterranean (FRLANT 233), Göttingen

Panofsky, E., 1955, Meaning in the visual arts: Papers in and on art history, Garden City

Pritchard, J.B. (ed.), 1969, The Ancient Near East in Pictures Relating to the Old Testament, Princeton

Schmitt, R., 2001, Bildhafte Herrschaftsrepräsentation im eisenzeitlichen Israel, AOAT 283, Münster

Schroer, S., 1987, Das Recht der Bilder gesehen zu werden (OBO 74), Fribourg

Strawn, B., 2005, What is stronger than a lion? Leonine image and metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and the ancient Near East (OBO 212), Fribourg

Weissenrieder, A. / Wendt, F., 2005, Images as communication: The methods of iconography, in: A. Weissenrieder / F. Wendt / P. von Gemünden (eds), 2005, Picturing the New Testament: Studies in ancient visual images (WUNT 193), Tübingen, 1-49

Weissenrieder, A. / Wendt, F. / von Gemünden, P. (eds), 2005, Picturing the New Testament: Studies in ancient visual images (WUNT 193), Tübingen

The authors are the chairs of the iconography program units at the Society of Biblical Literature (International and Annual Meetings) and the European Association of Biblical Studies.

Comments (1)

Interesting, though do we have a specific example of a new or improved interpretation of the Bible or of any passage with the aid of any particular iconographic information?

#1 - Martin - 09/05/2013 - 13:49