Leading proponents in biblical scholarship who adopted the term “reception history” as a method defined their work in different ways from that of reader reception. They developed a sense of the importance of, or the impact that, biblical literature has on society in a dynamic relationship between cultures and biblical texts.

Also See: The Bible, Gender, and Reception History: The Case of Job’s Wife (Bloomsbury T&T Clark, forthcoming)

By Katherine Low

Assistant Professor of Religion and Chaplain

Mary Baldwin College

August 2013

In an undergraduate introductory course on the Bible, I once used William Blake’s 21 plate series of engravings of Job from 1825 to introduce themes in the book of Job. After the lecture, one first-year student responded, “It was interesting to see how one absent at the actual time could portray the events just as they occurred based only on scripture and some imagination.” The student assumed that Blake held the ability to accurately portray biblical events. This assumption assigns Blake’s visual interpretations of Job much influential power. However, the student also understood that Blake stood at a significant historical distance from the original biblical contexts and needed something, in this case imagination, to bridge the historical gap.

The roots of Rezeptionsgeschichte (reception history) rest within these tensions of time, the gap between original literary contexts and social locations of readers throughout history. Working in the German university system in the late sixties, Hans Robert Jauss adopted the phrase “horizon of expectations” from an art historian, in that “horizon” acts as an entire set of mental expectations a reader brings to a text determined by one’s historical location, in the same way a viewer would bring a set of expectations to interpret a work of art (Parris, 151). From his area of literary studies, Jauss was influenced by Hans Georg Gadamer’s philosophy of the fusion of horizons. This philosophy suggests that a reader’s horizon is limited to what he or she can understand (historical roots), yet that limitation is not closed and still holds possibility. Any encounter with a text shifts one’s horizons; though not assimilation or harmony, an interpreter is introduced to another horizon and thus re-thinks his or her previous assumptions through the hermeneutical encounter.

Two German terms, Rezeptionsgeschichte (reception history) and Wirkungsgeschichte (history of influence or effect), both communicate how reading remains situated in history. Gadamer coined the latter term in his 1960 Wahrheit und Methode (Truth and Method). The term Rezeptionsaesthetik can be found in Hans Robert Jauss’ Towards an Aesthetic of Reception from 1982. In 1984, Robert Holub published an overview of reception history in English. For Holub, the most basic meaning of reception theory is a move from focusing on the original author(s) of the text to the readers of the text (Holub, xii). Given Holub’s definition, it comes as no surprise that when reception history emerged as a biblical scholarly method, many placed reception history with reader-oriented approaches, such as reader response. For instance, the Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation includes “reader-reception criticism” under the wider category of reader-response criticism (McKnight, 372).

Leading proponents in biblical scholarship who adopted the term “reception history” as a method defined their work in different ways from that of reader reception. They developed a sense of the importance of, or the impact that, biblical literature has on society in a dynamic relationship between cultures and biblical texts. John Sawyer, for instance, defines reception history in terms of Wirkungsgeschichte, as “the history of the effect the Bible has had on its readers” (Sawyer, ix). The focus shifted, as I see it, from the original roots of the term and its orientation within literary studies to a point of reference from within cultural studies. David Gunn, for instance, situates reception history under cultural criticism and reader-response approach under literary theory. Cultural studies involves texts and readers in reciprocal relationship (Gunn, “Cultural Criticism,” 204). The focus becomes not just on readers, but the relationship between the Bible and people, the creative interactions between readers, texts, and cultures. Furthermore, the categorization of reception history as a cultural studies method rather than a literary studies one expands ideas about what is “reader” and what is “text.” Cultural artifacts of all kinds, such as art, music, graphic novels, film, television, and other media are places in which all kinds of people have interpreted the Bible; they are sources in which the impact of the Bible can be seen by biblical scholars of reception history.

Today, use of the term “reception history” may be inadequate to capture all the tensions involved in its literary studies foundational assumptions about the primary existence of a text, and that one is capable of even reaching original “meaning.” However, reception history in a cultural studies sense has grown beyond the original roots of German literary studies. Reception history of the Bible traces impacts of the Bible in a diverse world of interpretive mediums from within a wide variety of societies and cultures throughout history. The key words include effects, uses, afterlives, impacts, and consequences of the Bible. This definition engages a large range of interdisciplinary approaches, including interreligious contexts of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Cultural studies is a broad approach, but it has some distinguishable characteristics helpful for reception history of the Bible. First, it engages a critical landscape, from established disciplines to new movements, with a goal to examine the relationships between cultural practices and power. Power, in this case, rests within the structures of society, constantly negotiated. Second, cultural studies assumes cultural subjectivity of knowledge, approaching relationships between observers and objects in terms of their constant interaction. Thus, an object of study is never far from its place in politics, religion, economics, or gender. As a result, any social practice is open to consideration in cultural studies, as even cultural products of everyday life produce some form of cultural knowledge. Traditional understandings of high/popular culture dichotomies, or classical canons, become decentered (Easthope, 171; see also Moore, “Between Birmingham and Jerusalem.”).

A collection of essays by Fernando Segovia begins with three paradigms of biblical studies—historical criticism, literary criticism, and cultural criticism. For Segovia, cultural studies, which is different from cultural criticism, is an emerging paradigm, an umbrella model that can hold underneath of it a wide variety of theoretical frameworks but pivots on an important hermeneutical key which he calls the ideological. The ideological mode of discourse within the paradigm of cultural studies focuses on contexts, social locations, agenda, agency, and politics of all compositions, texts, readings, and interpretations. Within this ideological mode, a joint venture of critical focus on relationships between texts and readers emerges, one that assumes that presuppositions of readers cannot be put aside nor can readers transcend beyond themselves to discover “true” meanings of texts (Segovia, 13-15).

Editors of the first series dedicated to the reception history of the Bible, the Blackwell Bible Commentary series, remain aware of the difficulty with finding and disseminating material from different times, places, and social locations. The guiding principle for authors as they attempt to catalog vast amounts of ways the Bible has impacted people is to emphasize the “especially influential or historically significant” interpretations (see the editors’ preface in the series, including Gunn, 2005). The exact criteria of what makes an interpretation influential or historically significant is not provided; what one author may consider influential another author may not. If one takes cue from Segovia, the ideological focus from within cultural studies may be a helpful criterion for reception history of the Bible.

When I set out to develop the direction for my project The Bible, Gender, and Reception History: The Case of Job’s Wife, I decided to engage reception history with an ideological area of study. My goal was to be transparent and intentional about the relationship between the critical lens of gender theory and reception history of the Bible. In my case, pairing reception history with a critical perspective on gender fits a discussion about a biblical marriage. Interpretations of the marriage of Job and his wife, a relationship of a man and an unnamed woman, reveal ideologies about gender roles. Gender theory analyzes sexual difference and social constructions of what it means to be a man or a woman. Gender theory reveals that cultural production impacts social formation. Ideal roles, or appropriate behaviors for men and women, are dictated to people from within their larger societies and need not depend on biological factors (for more, see Alsop, Fitzsimons, and Lennon).

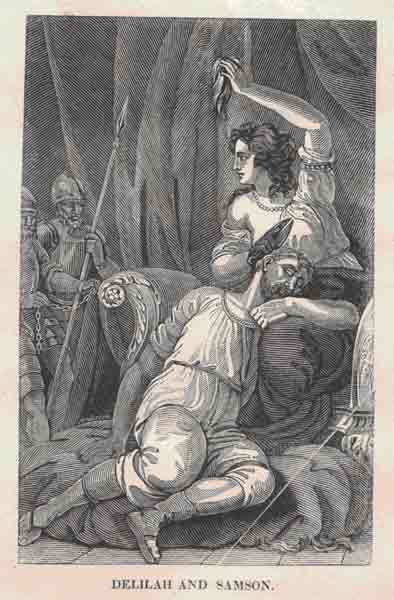

One example from reception history of the Bible is the dynamic relationship between Delilah and the cultural stereotype in the West of the femme fatale, the seductive and dangerous woman who leads men into dangerous situations (Gunn, 2005, 211-220). One of the most common scenes for artists to interpret, like the one pictured here by Alexander Anderson from 1848, depicts Samson sleeping between Delilah’s knees, while she clips his hair and signals the Philistines. Samson remains in a vulnerable position and often artists will expose Delilah’s breasts, a sign of artists interpreting her as a temptress.

Steel Engraving by

Alexander Anderson,

from The Cottage Bible

(Tiffany & Burnham,

1848). Photo: Katherine

Low

Delilah is not described as a prostitute in the biblical text, nor is her loyalty to, or love for, Samson expressed (Judges 16:4-5). In the end, she remains loyal to her own people, the Philistines. Such a loyalty would have been valued had she been an Israelite. Even before he connects with Delilah, Samson has a track record of going for foreign women (Philistine woman at Timnah, Judges 14, and prostitute at Gaza, Judges 16) rather than leading Israel on any helpful campaigns as a judge; he chased women, but beyond that, he chose to fulfill personal vendettas without a collective concern for his people.

Yet, a reception history of Delilah’s relationship with Samson in light of gender theory reveals less of these complexities and more ideological bents toward perpetuating gender stereotypes. Interpreters, artists and authors alike, overwhelmingly capture that one hair-cutting moment as the defining one between Samson and Delilah, thus constructing Samson’s vulnerability in the face of Delilah’s feminine sexuality. In a discussion of music about Delilah, Dan Clanton Jr. notes patriarchal and androcentric cultural assumptions at work that cloud and bias cultural interpretations of Delilah (Clanton Jr., 65-78). Questioning the passivity of “reception,” C. L. Seow prefers the term “history of consequences” to communicate the serious impacts biblical interpretations can have on culture (Seow, 368). Some interpretations make more lasting impacts than others, and often it is a lasting interpretation and not the biblical text itself that feeds cultural stereotypes about biblical women, including Delilah.

Gender theory is certainly not the only mechanism with which reception history of the Bible can reveal ideological aspects related to the impact of the Bible through the centuries. Social constructions of ideology are not limited to gender, but include socioeconomics, race, ethnicity, imperialism, disability, and deviance. When paired up with the critical lenses of ideological theories, the work of reception history can act as a mirror reflecting the ideologies at work throughout culture when it comes to the use and impact of the Bible.

Bibliography

Alsop, Rachel, Annette Fitzimons, and Kathleen Lennon. Theorizing Gender. Polity Press, 2002.

Clanton Jr., Dan W. Daring, Disreputable, and Devout: Interpreting the Bible’s Women in the Arts and Music. T&T Clark International, 2009.

Easthope, Antony. Literary into Cultural Studies. Routledge, 1991.

Gunn, David M. Judges. Blackwell Bible Commentaries, Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

Gunn, David M. “Cultural Criticism: Viewing the Sacrifice of Jephthah’s Daughter.” In Judges & Method: New Approaches in Biblical Studies, edited by Gale A. Yee, 202-36. Fortress Press, 2007.

Holub, Robert C. Reception Theory: A Critical Introduction. Methuen, 1984.

Low, Katherine. The Bible, Gender, and Reception History: The Case of Job’s Wife. Bloomsbury T&T Clark, forthcoming.

McKnight, E.V. “Reader-Response Criticism,” in Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation, ed. John H. Hayes (Abingdon Press, 1999), 372.

Moore, Stephen D. “Between Birmingham and Jerusalem: Cultural Studies and Biblical Studies.” Semeia 82 (1998): 1-32.

Parris, David Paul. Reception Theory and Biblical Hermeneutics. Princeton Theological Monograph Series, Pickwick Publications, 2009.

Sawyer, John F. A. A Concise Dictionary of the Bible and Its Reception. Westminster John Knox Press, 2009.

Segovia, Fernando F. Decolonizing Biblical Studies: A View from the Margins. Orbis Books, 2000.

Seow, Choon-Leong. “History of Consequences: The Case of Gregory’s Moralia in Iob” Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 1 (2012): 368-387.

Comments (1)

Reception can take many forms. The reception of the name 'Delilah' in the Anglo world is surely influenced by its assonance both with 'lie' and with 'delight', so she becomes an early version of the no-good beautiful woman who so delights film noir audiences. The assonances offer an example of completely accidental features of the receiving culture that tell us absolutely nothing about the original - though a delightful liar, or at least secret agent, is what Delilah is.

At another end of the scale is purposive reception, where a translator or interpreter may use his original to make a fresh point. I'm thinking of the way the Septuagint renders Philistines as allophyloi, a mixed bag of foreigners, which in this and other passages creates associations of ideas remarkably different (or so it strikes me) from those which arise when we read 'Philistines'. 'Assorted foreigners' suggests rootlessness, having no right to be there, hence moral decay: so Delilah/Dalida feels like a drifter seizing an opportunity to get rich quick. That's purposive reception for you.

#1 - Martin - 08/17/2013 - 13:29